You Can’t Have It All: Princetonians Respond

Princeton is a family. One of the ways I know this is that Princetonians of every generation have not hesitated to write me with their responses to my cover story for the July/August issue of The Atlantic, titled “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.” We attract an extraordinary pool of talented young men and women every year by making it clear that the hallmark of a Princeton education is intensive faculty engagement with students; why should that stop just because students graduate? And indeed, I have laughed, cried, and learned from these responses (more than 100), just as I always do from the students in my classes.

Let me review some of those responses, organized roughly by generation. One of the fiercest negative ripostes I received was from a cardiac anesthesiologist who described herself as a “Tiger family member” and who worked while her children, now adults, were growing up. Her point in writing to me was that I was completely out of touch with reality, due to my ivory-tower life. “Everything you mentioned has been dealt with by working women for the past 30 years. For 50. Forever.” This correspondent made her career work with a husband who applauded her more-rapid career advancement, took the kids to the ER when they were hurt, and made sure they got new shoes when she was too busy to notice shoes were needed. She argued, reasonably enough, that “patients rupture their appendixes around the clock,” and cannot be put on hold for a kid’s lacrosse game. She derided my suggestions for change with regard to more flexible workplaces and more variable career trajectories.

We’d like to hear your reaction to the views expressed in this essay. Write to PAW, email paw@princeton.edu, or post in the comments section below.

Responses will be published in a future issue and at PAW Online.

This reaction was not uncommon among women about 10 years ahead of me; they were uniformly surprised that “this is news.” It isn’t news to the women who have lived it. But as I explained in the Atlantic piece, my generation has not been honest enough with younger women about how hard it is, telling them that they can make it work if they are just committed enough and marry the right guy. And younger women and men are no longer willing to accept promises and bromides (starting with the assumption that everyone can get a job!). What I have heard more than anything else from hundreds of younger men and women is gratitude for my candor, whether they liked my message or not.

Perhaps we have not been honest enough with ourselves, either. A woman from the Class of ’76 wrote about her trade-offs in deciding to commute rather than move her son away from a house and community he loved. Then “the teenage years hit, and I didn’t want to be missing my children’s lives,” she wrote. She added, simply and sadly, “I looked around and noticed that so many of my female friends in the Class of 1976 had no children, had one child, or gave up working.” That is the toll that we have not been sufficiently willing to acknowledge as a social and economic problem. Another woman from a slightly later class, an enormously talented musician, reported that she pulled back from her musical career to give one of her children the extra attention he needed; a decade later, he is thriving and she has resumed her music in a different way. She added that although Princeton has done a great job of celebrating successful alumnae at events such as the “She Roars” weekend in 2011, “the women who spoke and were featured in many of the wonderful programs did not represent the majority of women attending the event. I know many brilliant, talented women who have made sacrifices in their professional lives who will never be featured in an event like that.” And yet their stories also need to be heard, valued, and taken into account by younger women and men who seek to have both career and family going forward.

On the other side of the coin, Lainie Ross ’82, who earned a medical degree and a Ph.D. and now practices pediatrics and teaches medical ethics at the University of Chicago, confirmed how hard it is to achieve a balance. She wrote that the dean of the faculty once asked her to “talk to the female medical students about work/life balance. I responded, ‘There is none.’ ... I sent him a YouTube video of a guy juggling electric chain saws. He agreed that I was not the right person to give the lecture!”

Moving forward to the 1990s, a number of alumnae reported being surprised by the compromises they have had to make. One wrote that “as a law student, I generally stayed away from self-conscious involvement with ‘women’s issues’; I thought my generation was past that kind of thing.” She has found, however, that her own ability to have both a career and children has depended heavily on the support of neighbors and friends in her parish, leading her to emphasize the importance of revitalizing institutions such as neighborhoods, churches, and social groups that can support families and working parents in particular.

One working mother with young children told me that her sister had sent her the article when it came out and wanted to discuss it. My correspondent, however, had been traveling for work, “followed by deep child immersion.” She flagged the article in her inbox, finally reading it “under the covers at 1 a.m. ... lest my husband chide me for never sleeping.” This again was a familiar theme: Many working mothers wondered how I or The Atlantic expected them to read anything longer than a headline.

A member of the Class of ’96 said she went to law school late, starting as an associate at a “BigLaw” firm that gave her “a generous maternity leave and the opportunity to work at ‘reduced time’ (40 hours a week) for the first six months” after returning from leave with her second child. But at the end of that six-month period, “I was told by the all-male leadership of my department that I could not continue on a flexible schedule, as it would hurt my professional growth.” She left, angry and frustrated, for a small firm that pays her a much lower salary. She concluded with a simple but overlooked point in our money-obsessed culture: “Flexibility is as valuable as compensation.” I would put it more broadly: Having a life that is more than work — living in the round — is as valuable as compensation. After all, Princeton admitted the vast majority of us precisely because we were multidimensional.

Still another ’96er, a tenured professor of economics, wrote of her decision to go to work late and leave early, go to fewer conferences, and write fewer articles so she could spend time with her three children. In one of the most poignant messages I received, but one that is echoed by so many others, she wrote of her gradual awareness “that what holds me back professionally is ultimately my own unwillingness to be less present as a mother. Coming to that realization has helped me sort things out for myself, but there is still a sense of loss, and a sense of betrayal to my own younger, more idealistic, ambitious self.” It is precisely that sense of betrayal — indeed, in many cases, of failure — that we must address and eradicate; we owe it to our friends, sisters, daughters, and mothers.

Younger men also are questioning the work environment they have inherited. One former student, a man, wrote that “as long as it’s viewed as more ‘manly’ for men to prepare for marathons than to spend time with their children, those of us who want an ambitious career and a healthy family life — whether men or women — will be professionally disadvantaged.” Another weighed in with the point that “older male mentors have advised me to work my butt off for the first few years after my daughter is born since those years ‘don’t really matter that much since she won’t remember whether you were home or not.’ That just doesn’t seem like the way it should be to me ... . ”

A talented young Princeton faculty member who is leaving the University said that a central reason for his departure is work-life balance. He wrote, “The reactions I have received from colleagues, friends, and even strangers when I tell them what I’m giving up in career goals for personal goals directly parallels what you’ve faced. It strikes me that men can’t have it all, either — and when we choose building a family over building our careers, we also take flak because it violates cultural expectations.” In a similar vein, a 2005 female Ph.D. recipient said: “More than once I have been advised by senior women to avoid committee work on things like day care and family-friendly policies because it will make me look like a whiner, not serious or ambitious enough.”

From the aughts generally, a chorus of thank-yous, many moving and deeply felt. “You articulated something that is weighing on the mind of just about every woman I know,” wrote one of my former thesis advisees. I also heard from Katie Mullen ’03, who had saved me in my first year as dean by trudging a mile and a half through heavy snow to my home to care for my two boys, then 4 and 6, so that I could meet the former president of Ireland, Mary Robinson, in my office (the schools were closed; my husband was out of town; and my caregiver was snowed in). I have never forgotten Katie. She had been raised by a working mother and understood my predicament. I bless her and her mother to this day!

Ten years later, Katie wrote: “I have recently challenged my own thinking about the messages I had been receiving or interpreting from the successful women I saw, including women like you. The messages I felt I heard were always the same: You can have a powerful career and a happy family if only you work hard enough (and provided you are willing to be sleep-deprived for decades at a time). Mommy-track jobs were to be dismissed, and taking time off was a sign of weakness that others would interpret as lack of commitment. And yet, of all the powerful, accomplished women I worked with, none had a model that I aspired to. Some seemed perpetually miserable that they were away from their children; others would be so focused on work that they barely spoke to their children on the phone when they called. I knew I didn’t want to be either of those!”

When did wanting to be with your children become a sign of weakness? When I told acquaintances that this was one reason I was glad to return home after two years with the State Department, many reacted with disappointment. When did it become fine to say that you were leaving a job because you would lose your tenure otherwise (after two years of public-service leave, Princeton revokes your tenure), but not acceptable to say you were leaving because your teenage sons needed you? What has happened to our values as a society?

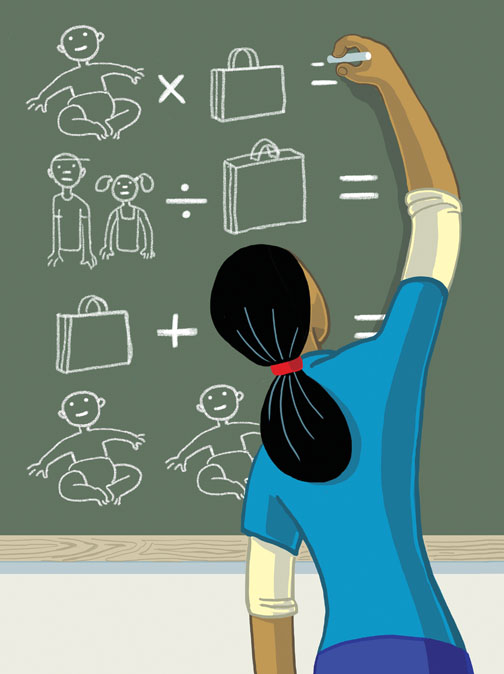

This is an important conversation that Princetonians need to have. My father, Class of ’53, always told me that Princetonians “take their work seriously and themselves lightly.” And as my friend and mentor Nannerl Keohane (the former president of Duke and Wellesley) says, few things rival the deep satisfaction of having a profession that you love and have mastered. But one of those few things is the joy of deep connection to those we love. Some people are prepared to choose one over the other: Some of our most highly accomplished professionals choose not to have children, and some of our most extraordinary parents devote themselves solely to their families. But in my case, at least, I never have had any doubt that working full time makes me a better mother (I would be frustrated and unhappy if I could not pursue the work I love); and being a mother has increased my patience, improved my judgment, and led to valuable self-knowledge that makes me a better leader and colleague. So why should we look to the professional as the principal yardstick of prestige?

Cale Salih ’10 wrote me an extraordinary letter on this point, beginning with the reflection, “I have often wondered why I should feel guilty for simply daring to say yes to a momentous personal opportunity.” She continued: “For the past two years, I have been consistently congratulated for making career choices that reflected great ambition, but often came at the expense of personal relationships. Now, I am considering moving to be closer to my long-distance boyfriend. In conversations with people in my own cohort, I find myself making up pretexts to hide the real reason for my move. On occasions that I do reveal the most important motivation behind my move, I am often met with subtle but noticeable eye rolls or worse, patronizing lectures: ‘You’re too young to make life-altering choices for a boy.’ While making life-altering choices for a relationship is seen as weak or naive, making similar sacrifices for a job often is seen as a sign of strength and independence.

“No more do I want to be unemployed than do I want to be the power woman who goes home after work to eat moo shu pork alone in her apartment,” Cale said. “Why, then, should I be proud of investing in one goal, and be embarrassed of investing in the other?”

Cale concluded with a comment on her Princeton education, one that should engage every reader of PAW. “Princeton taught me well how to succeed and how to value professional ambition,” she wrote. “But after the cutthroat Ivy League environment, I am trying to teach myself to value relationships. Ironically, the only way I can do this is by looking at my relationship as a professional goal, the only thing I know how to attain.” As a Princeton professor, I am gratified that we have inculcated high standards and professional ambition. But we are falling short if we are not also teaching our students to value their own humanity, which is inextricably tied to the love, care, and dignity we accord others in our lives.

One of the things I tell people about Princeton is that it provides a moral education as well as an intellectual one, through the Honor Code, the ethic of Princeton in the nation’s service, and the overwhelming awareness that being a Princetonian means being part of a community of values as well as minds. Those values include standing up for what is right. That is the most important message that I try to communicate to my children, along with admitting and taking responsibility for their mistakes. Deciding what is right often takes the critical thinking and independence of mind Princeton values so highly. In the words of a young lawyer from the Class of ’05, the mother of a 2-year-old: “I find myself constantly searching for the right answer to the work-life question — even just the right answer for myself.”

As a society, as a university, we say we value family. But when women and men choose family over professional promotion, they very often are devalued. It is right that they should not advance as fast in their careers as their peers who have chosen to prioritize professional achievement, and I certainly am not suggesting that we should devalue professional ambition. But people must have the option of pursuing a different but equally respected path, where we see them as peers who are investing equally in the personal and the professional, in their communities, and in the prosperity and well-being of the next generation as well as in their own careers.

I often have told the story of deciding to leave Harvard for Princeton because I was inspired by Shirley Tilghman’s vision for Princeton, how Princeton could be a leader intellectually, as always, but also socially, in terms of diversity and women’s leadership. May we now lead in educating all of our students, women and men, to make the choices and insist on the changes necessary to ensure that they have equal opportunities to make equal use of all their talents over their lifetimes. Let us forge our own standards of success and live up to them with pride, courage, and strength of character, in the best Princeton tradition.

Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 is the Bert G. Kerstetter ’66 University Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton, and a former dean of the Woodrow Wilson School. She returned to Princeton last year after spending two years as the director of policy planning at the State Department.

2 Responses

Kathryn Clutz ’88

10 Years AgoA parent's most important duty

What is lightly referred to but not directly addressed in this article (Perspective, Sept. 19), and the Mommy/career debate in general, is the needs of the children. As anyone who has been a child can tell you, children need time, interest, and affection from their parents to feel loved. No matter how good the nanny, babysitter, grandmother, or teacher, children need their parents. The attention, affection, or perceived lack of interest from their parents (and children tend to take things personally, no matter what the reason for a parent’s physical or emotional absence) will impact the way children feel about themselves for the rest of their lives, and their capacity to establish rewarding relationships as adults in love and in work. I don’t think there is any responsibility that should be taken more seriously than being a parent – you are essential to the physical and emotional well being of your children, and you are irreplaceable.

Julie A. List ’78

10 Years AgoBroaden the work-family discussion

Professor Slaughter, as a proud member of the Class of ’78, I am pleased to know that we crossed paths at Princeton, although we did not know each other and have never met. Your accomplishments, both professional and familial, are admirable, and your struggles to fulfill career goals while maintaining personal commitments as a hands-on mother are ones that many of us can relate to.

When I saw your piece in The Atlantic, I had many responses, even to the title: Who ever said that women, or anyone, for that matter, can have it all? Where is it written that there is such a thing as a perfect work/family balance? And isn’t it always a juggling act, given the huge demands of parenting itself?

Second, I liked your article very much, and found it honest in all ways. I agree that there is little preparation for the impossibility of doing everything, once a working woman decides to have children. I could understand perfectly the pull to be closer to home, especially as children reach the chaos of adolescence. Similarly, it was clear that many people, both women and men, would not feel this pull, and would put their career goals above all else. Having carried a child for nine months, given birth, and raised a baby through the teenage years, I would find it physiologically and psychologically impossible not to be deeply connected to the struggles that my child experienced.

As the child of a single parent, I saw the push and pull my mother went through in the early ’70s, as feminism was trying to spread its wings, and there was, as yet, no prediction about the impact this would have on the children. In fact, my mother, Shelley List, a journalist and novelist, published an op-ed piece in The New York Times in 1972 that was an open letter to me and my sister, then 15 and 11, about her quandaries in trying to fulfill her dreams of working as a writer while, in effect, neglecting our emotional needs (“To Julie and Abigail,” March 17, 1972).

From this perspective, as a white, middle-class person born to a heterosexual mother who divorced my father when I was 9, I contemplated all of those who are not mentioned in your article nor in the responses you received as published in PAW (Perspective, Sept. 19). In most of the articles I have read about feminism, the work/family balance, and the opportunities of advancing professionally, there is little attention given to issues of race, class, or sexual orientation. Thus, these struggles seem to apply, by default, only to white, middle-class, married, straight, women. It is primarily white women who have the opportunities to get advanced education, or have the privilege of making the choices you and I have had the luxury of making. In addition, we are the ones who have raised children within heterosexual relationships, which until recently were the only kinds of couples who could reap the benefits of a legal union. We have the choice whether or not to work, in many cases, and to decide whether we prefer to work part time when our children are small (as I did) if we have husbands or partners who take the parenting role as seriously as we do. And, finally, being middle-class, we also have the luxury of deciding if we can afford to hire someone to help us with our children.

For single parents, who would like nothing more than to fulfill career goals, there are the pressing issues of finding good child care, paying the bills, and stretching themselves very thin, financially and emotionally. For women of color, especially those who are single and poor, who always face some form of overt or covert racism and ever-present institutional racism, the choices are fewer still. And for lesbians, there is a whole other set of obstacles and legal challenges that they must face.

So, while I agree with the struggles we have as white, middle-class, heterosexual women, I cannot wholeheartedly support the argument without a more thorough investigation of how trying to strike a work/family balance affects all women. From the start, the ideals of feminism have applied primarily to white, middle-class women, and, as a result, I fear we are neglecting many of our sisters in this discussion, and not only our children.

This does not minimize the very real struggles you identify in your article; neither does it negate all of the points you make so well. I just wish that we, as professional women and mothers, would broaden our exploration and learn not only from each other but from other women who face different and more difficult struggles.

Thank you for your contribution, as a Princetonian, as a professional, and as a loving mother.