INBOX

Join The Conversation

PAW invites readers to participate in thoughtful and respectful dialogue. Here’s how the process works.

1

Find the Story

Every article includes a “Join the Conversation” form at the bottom. Scroll down to complete the form, and be sure to include your name, email address, and Princeton affiliation.

2

Share Your View

Read PAW’s commenting policy for details about our guidelines and expectations. Responses are limited to 500 words online and 250 words for print consideration.

3

Submit Your Response

All comments are reviewed by PAW’s editors. When a comment is published, an email notification will be sent to the address you provided.

Popular Inbox

January 03, 2025

Princeton/NFL Draft Trivia

November 14, 2024

Concerns Over SPIA’s Strategic Direction

November 12, 2024

Student Referendum

January 06, 2025

More Glory Honors

December 02, 2024

Support for Hegseth

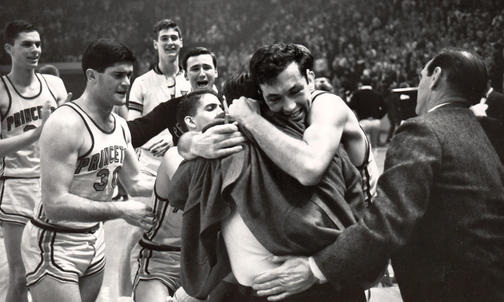

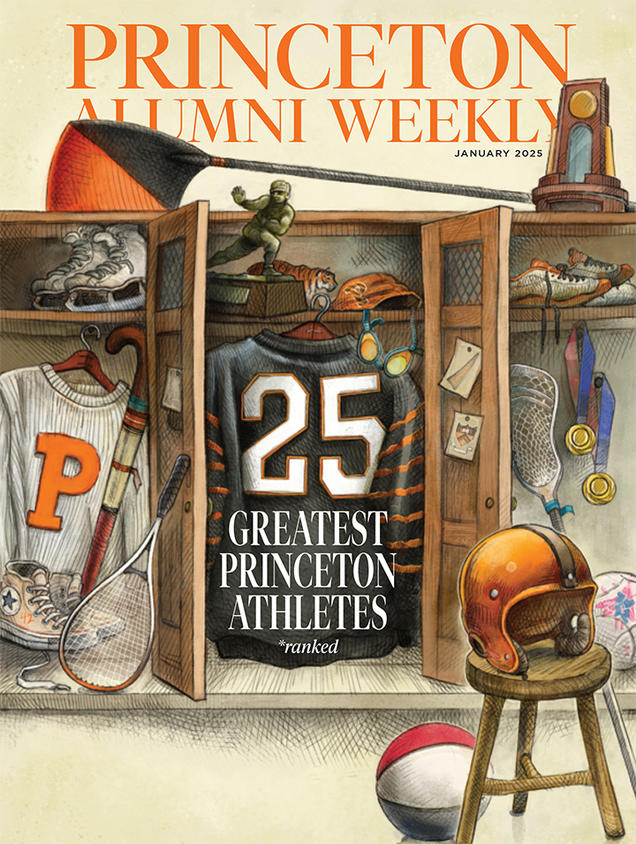

The 25 Greatest Athletes in Princeton History

A panel of experts selected these athletes from a list of many, many — remember, we said many — extraordinary Tigers

January 24, 2025

Groundbreaking Rowers Brown ’75 and Lind ’06

January 23, 2025

List of Athletic Greats

January 21, 2025

Sella ’50, a Special Athlete

What Was Defense Secretary Nominee Pete Hegseth ’03 Like at Princeton?

Hegseth, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for defense secretary, was a basketball player, a politics major, and a brash publisher of The Princeton Tory

December 19, 2024

Questioning Hegseth’s Qualifications

December 06, 2024

Familiar Princeton Background

December 06, 2024

Princeton’s Role in Hegseth’s Rise

PAW IN PRINT

Newsletters.

Get More From PAW In Your Inbox.

January 28, 2025

Climate Crisis in the Classroom

Christine Brozynski ’10