Edward Norris McLean ’45

Ted died July 4, 2009, after falling from a ladder two days earlier.

He entered Princeton from Menlo Park (Calif.) Prep School, following in the footsteps of his father, Dr. Edward McLean 1908, and joined Dial Lodge. He was in the Navy V-12 program during the war and then attended Johns Hopkins, where he received a medical degree in 1947 and met his future wife, June Cutts, a nursing student.

Ted, an ophthalmologist, served with the Navy in Japan from 1954 to 1956 and then returned to private practice, spending a lifetime with June and their children in West Linn, Ore.

Throughout his life, Ted enjoyed skiing, fishing, boating, and camping with his family. He was an avid photographer and gardener, and was noted for his roses. He loved music and played the cornet in his youth.

Ted retired in 1994 from the Eye Health Northwest Clinic, which he had founded in 1954, so his practice spanned four decades.

He is survived by June; his children, Ed Jr., Thomas, Marianna, and Kenneth; seven grandchildren; one great-granddaughter; and his sister, Margaret.

The class expresses its sympathy to them all.

Paw in print

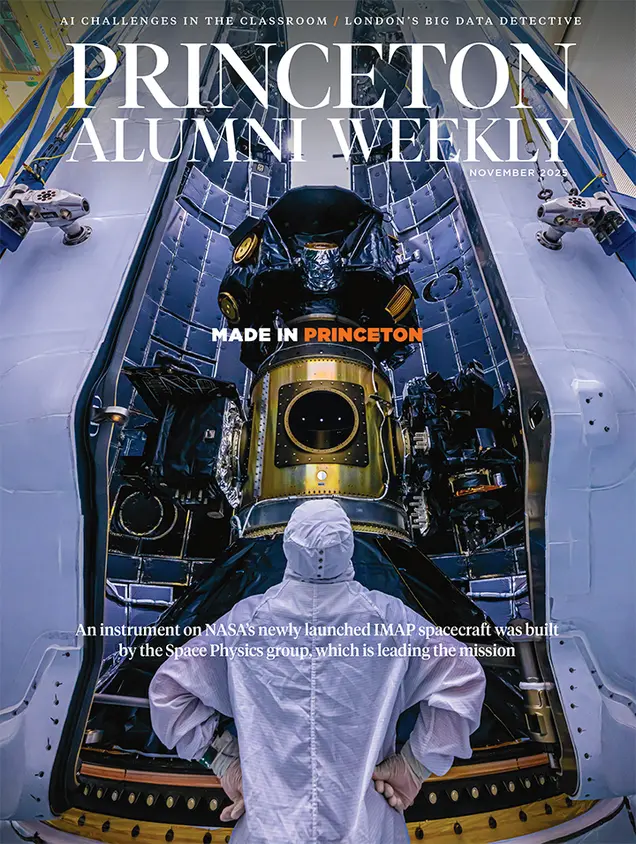

November 2025

NASA’s new IMAP mission, London’s big data detective, AI challenges in the classroom.

No responses yet