PAWcast: Ge Wang *08 on Computers, Music, and ‘Artful Design’

Taking a closer look at how technology shapes the way we think and act

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students.

TRANSCRIPT

Allie Wenner: Hi, I’m Allie Wenner, and today I’m here with Ge Wang, who is constantly pushing the boundaries between music and technology. That’s him you’re hearing playing the X-Files theme song using an app he created called Ocarina, which lets users make their own music by blowing into their smartphone’s microphone and then creating different tones by pressing their fingers on the screen. After getting his Ph.D. in computer science from Princeton in 2008, Ge co-founded the mobile music startup company Smule, and the apps he created through that company have reached more than 200 million users. Now he’s a professor at Stanford in the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. And as if all of that wasn’t enough, he just wrote a book called Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime, which was released last September. Welcome Ge, and thank you so much for being here today.

Ge Wang: Thanks, Allie. Thanks for having me.

AW: Yeah, of course. So let’s talk about your new book, Artful Design. What is the concept of Artful Design and how does it relate to the work that you do?

GW: So Artful Design. Well, I’ve been writing this book for three years. It’s a comic book, but to be honest — I don’t really know what it’s about anymore myself. I think it’s about how we shape technology, being very cognizant of the ways that the things we shape with technology comes back to shape us. And you think about, like, kind of just our everyday lives. Today, we’re surrounded by technology, and most of the time we think of them as kind of tools that kind of help us do things, but the way in which things are shaped come back to, I think, shape us. Shape our behaviors; shape the way we think; shape our relationships with each other. And so this book is kind of a meditation on that, but also thinking about how to translate that as builders, as engineers, as designers into the things we actually build with technology.

AW: And earlier when we were talking, you kind of described — you described it as sort of a textbook. Is this something you would give to a classroom? Who’s the target audience for this?

GW: Well it is kind of a strange textbook. It’s a comic book. It’s a 500-page comic book … right now I’m actually using it in my course at Stanford, in my “Art of Design” course, we’re using this as the primary textbook and we’re reading about a chapter a week, and there are eight chapters spanning everything from audio-visual design to programming to interface design to game design to kind of the ethics of design.

AW: What’s that class called? What are you doing in that class?

GW: So, the course I’m teaching this term is called “Music, Computing, and Design: The Art of Design,” and next quarter I’m teaching a course for first year students called “Design That Understands Us.” Both of these courses will use this book kind of as a strange textbook. It’s probably the most comic-y, colorful textbook one might use.

AW: Yeah. I’ll agree. I mean, I’ve never really seen a book like this before. I mean, it’s like, probably like Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban like thickness and heaviness, but it’s also kind of like a comic book. I mean you have like talk bubbles and then lots of different pictures, but they’re actually like digital photos and not, I guess, cartoon drawings. Why publish a book in this particular format?

GW: So, yes. The medium as you notice is I guess what they would call a photo comic. So, most of it is not drawn. Most of it is actually photographs, and for me, I think, I feel like writing a book about design, it felt like — I really should very intentionally and very clearly have designed the thing, so this is, well, as they say, the medium is the message, and the medium here, really I wanted to use that to shape, actually, the message of the book, and that itself is an example, I think, of design. So I wanted this kind of recursive thing of talking about design but in a way that itself is design, and the book — well, it, like all books, it’s an artifact of design, this one a very specific one in the medium of the photo comic.

And the second thing I would say is that the — well, it’s a nonfiction book, so for me — and I grew up with comic books. I grew up reading Tin Tin — The Adventures of Tin Tin, Spiderman, Batman, Watchmen, you know all these — Asterix — these are, I think stories that are told fictionally, I like them drawn in a way, because, you know, yes, we have like movies made from superheroes like Batman, but those, if there weren’t a comic book, you’d be wondering, like, “Wow. Who’s that playing Batman?” Like, there’s a fiction-ness, another layer that you wonder about, like in a comic book, so it makes sense that it’s drawn, but in a nonfiction book, it’s about kind of everyday things. I think I wanted to remove that level of — I don’t know. There’s no acting. It’s actually, this is what it is. So it made sense that a nonfiction book about design uses actual photographs.

AW: There’s something like 1,600 photos in this book and many of them are of you? Pictures that you took of yourself?

GW: Yeah, so there are over 1,600 photos in this book. I took over 1,300 of them. The rest came from Creative Commons, public domain, or specific ones obtained by permission. The ones I took — yeah, many of those are, well I took more selfies than is probably advisable for anyone. I had like a whole rig where I would be able to shoot kind of selfies, either at a distance or up close, and there were times where I would just film myself talking at the camera only to go back and actually pull stills, frames out of the video to be used in this. I have this matrix of like, probably like 800 different stills of me just in really different gestures, different — giving off different affects, and every time I needed to say something in the book, I would scan through this rather large matrix of me having talked to the camera and find the closest one that matches the affect I was looking for.

AW: Geez. Sounds like quite a process.

GW: It was. Took me three years to write this book, and it was transformative for me just as a way to recompile my brain.

AW: And flipping through the pages here, the content is kind of wide-reaching. You know, you go into the genesis of the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, the Stanford Laptop Orchestra, and everything from Ocarina, some of the music social apps you’ve created and also computer programming, but you kind of really bring them all together and show how they’re interconnected. Do you see this book as sort of like the culmination of the various different kinds of work that you have done in the span of your career so far?

GW: I think the book very much began as that. So I do computer music. I’m a computer music researcher. I build instruments, tools, games, programming languages really in service of music so people can use them as tools to make music with the computer. And so, really computer music is very much kind of the main vehicle for the book, but as you mentioned, I think I’m using computer music really as a concrete case study and using really technology and music, two things that I think we really all find in all of our lives — there’s something universal about both of these things — to look at technology and its shaping more broadly. So, at some level it’s a computer music book. At some level, it’s actually an ethics book. It’s a book — that asks, “what does it mean to design well” — that’s in the craft of design. I think it also asks, “what does it mean to design ethically, and why should we bother to do that? What does ethics have to do with design and technology?” But of course, this is a topic that’s very top of mind today.

AW: Sure. Sure. And speaking of computers and music, which you were bringing up a second ago, I want to backtrack to your Princeton days for just a minute.

GW: Yes.

AW: And for your dissertation here in the computer science department, you actually designed an audio programming language called “ChucK,” so I’m wondering what — what does that mean? I mean, how does one program audio and how similar is this program to like other mainstream programming languages like Python or JavaScript?

GW: So yes. So, ChucK is a computer music synthesis language. You can use it to generate sound, but really what you’re doing is you’re writing code to produce sound and you can also write code to organize the sound into music, and you can also use ChucK to take sensor input. For example, the trackpad on your laptop, or the keys or other sensors or a joystick, and then map them into sound output and to do that with the intention of creating a musical interface with the computer. That’s kind of what the laptop orchestra was all about. In my time at Princeton, which was from 2001 to 2007, I had the fortune of working with my adviser, Perry Cook, who is in computer science but also is jointly appointed in music, and professor Dan Trueman who is currently, of course, still here, and they were kind of my mentors, they were my heroes, and they still are both of those things. And, so, I think really it was kind of this adventure about thinking about, how do we use the computer to shape it into something that we can make music with — make music that is meaningful, you know, that matters to us, but also to explore what new possibilities exist for this medium of the computer.

AW: That’s so awesome, and I mean, did ChucK and your dissertation have any role in the creation of Smule?

GW: Very much so. All these things are really connected. I started working on ChucK, I think rather early in my Ph.D. here at Princeton and then Perry and Dan started the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, and I was very fortunate to be really part of that, to think about how to — what tools we used; how do we teach this; how do we shape this, and will this even work, right? And we built a lot of instruments using ChucK and other tools in the laptop orchestra. And later, I started it on the faculty at Stanford in 2007, and there I started the Stanford Laptop Orchestra, but kind of this experience of working with a computer, with building tools, with building instruments, those kind of translated into the kind of things that I would design in Smule. In fact, I think Smule came out of the culmination of having done all these crazy whimsical things with computers and music, but then, here comes the iPhone. And here’s a smart phone which you can program and has a lot of sensors. It has a powerful CPU; it can do graphics; it has sensors; it can take user input. It’s always connected to the Internet, and so, yeah, it’s like this continuing pooling of different elements, but they all seem to end up fitting together one way or another.

AW: Yeah, and I’m glad you mentioned the release of the iPhone, which I think was like late 2007, which would have been perfect, I mean, right, when you were kind of wrapping up here and starting to venture out into the technology/computer-programming world. I know the first app was Ocarina, which I think came out in 2008, and you were the chief designer and architect. Yeah, so it’s been on the iPhone store since 2008, and now it’s one of Apple’s all-time top-20 apps. So I’m wondering if you can talk about that app and maybe some of the other apps that you’ve been involved with at Smule and kind of how the company has evolved over the last 10 years as so much has been changing in tech and how we use our phones and our tablets.

GW: Yeah, absolutely. Ocarina is an app for your iPhone but you play it — I’ve asked you to use your iPhone in a way that you don’t typically think of as a how you use a phone. You know, typically we have a phone. Might use our thumb or different fingers to type into, but we think of it as this like portal into this virtual world. But Ocarina’s like, no. You hold the phone like you might a sandwich and you blow into it to make music and it’s a very physical, kind of a usage of your iPhone. The whole design behind Ocarina is that this is — your phone is not simulating a flute-like instrument; your phone is the Ocarina, and you blow into it and you use your fingers to control the pitch and you tilt it to control vibrato, and it’s really kind of this playful toy, a musical toy for your phone.

I think from the beginning, much like the laptop orchestra, it’s really thinking about, as broadly as possible, what are the possibilities, musical possibilities for these kinds of computer technologies, whether it’s a laptop or mobile phone. And I think this kind of thinking has shaped all subsequent apps at Smule, and in terms of this belief, this value, if you will, that music making does a person good, and we can shape technology to help people really discover that, really about themselves, and it’s not like — it’s not even music education. It’s more like self-fashioning in a way. It’s like, hey, you can have fun being expressive playing music, and you can do this for the sheer, intrinsic joy of doing that, and hey, it’s music. You know, it’s something that any normally-endowed human being would — I think this speaks to something there’s — music and dance is something that has been with us, well, throughout all of history.

And the other component of Ocarina is the social component, right? It’s this component where, well on one hand you blow into the phone to make music, but you can also listen to other people blow into their phones around the world. Strangers playing everything from “Amazing Grace” or “Legend of Zelda” from Indonesia, the X-Files from Florida, or “Final Countdown” from Korea, and it makes you wonder: Who are these people, and why are they playing that particular tune? And of course, the app gives you no answers. It’s not designed to, but it’s designed to — well, to make you wonder and to feel connected to others. So I think the social dimension has also been something that’s carried through and is pervasive through, really, all the Smule apps.

AW: Yeah, and to go back, I know you mentioned earlier about how you work at Stanford now. You’re a professor there, and you started the Stanford Laptop Orchestra, which I think is at least loosely based on the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, which was started when you were in grad school here as you mentioned. Could you talk a little bit more about what a laptop orchestra is and how it works?

GW: Well, Stanford Laptop Orchestra, or SLOrk, is more than loosely based on the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, PLOrk, right. The variety and the innovation comes from the people who are in it year-to-year. They come up with new and crazy and wonderful and whimsical things. New instruments, new pieces. So, it’s really a medium for designing instruments with computers and performing — writing music for those instruments and performing that music together. So, Stanford Laptop Orchestra, or SLOrk, has now been around for 10 years, since 2008. PLOrk has been around since 2005, so I think the medium, the Laptop Orchestra — wow, we’re in our like 13th or 14th year in this — at this scale and in this form. Oh, and what was the other part of the question?

AW: So, I guess, how similar are SLOrk and PLOrk to a regular orchestra? I mean, are people set up? Are there different sections? Are there a similar number of musicians?

GW: So, it’s similar in scale, perhaps more to like a chamber ensemble, and very much Dan Trueman had this idea that a laptop orchestra plays a kind of electronic chamber music, meaning we would have anywhere between four to maybe 20, sometimes more kind of stations, where each station is like a laptop, a human, and a special hemispherical speaker array. Now the speaker array is meant to have the sound be local to the player and the computer. So in a way, we’re trying to figure out the possibilities of computers for music, but on the other hand, preserve something that’s really nice about traditional acoustic instruments, which is the sound. You know, like when you play a violin or a ukulele, the sound naturally comes from the artifact, and that, I think, acknowledgement or awareness completely changes the way you would actually design an instrument for something like a laptop orchestra, which in turn changes the way you think about writing music for that instrument, changes how you perform it.

So, the laptop orchestra is — it’s a kind of orchestra where, if you’re at a concert, it’s — the closer you are to the orchestra, the better. You almost want to be, like in the middle of it because then sound is coming from all around you. You’re almost in this garden or sometimes wall of sound, and in terms of how people play their instruments in a laptop orchestra, it’s very diverse. Sometimes, there are people, yeah, we’re just barely touching our computer and just staring at the screen, and you’re wondering what in the world are they doing. In other pieces, it’s extremely physical, where we are actually jumping around or waving our arms, in ways that are very visible. So, the way you would play these kind of instruments, is really dependent on that particular instrument. Some of them have wide gestures; some of them have very small ones. The sound is really — the thing about a computer is that you can generate a sound that you just can’t hear anywhere else, so sometimes we’d get sounds that are just kind of out of this world, so to speak, and we think about how do we meaningfully play those sounds and shape them into music and shape the music together as a group.

AW: And, Ge, so much of your work revolves around not just creating music and creating new instruments, but around also making them accessible and fun for people of all musical abilities. What do you love about this?

GW: Well, I feel very lucky that my job seems to involve making things that help other people make music or rock out, and sometimes I write music, and so this whole act of design — it’s kind of a privilege to do. At the same time, I think it reflects something of — just this belief that making music is like a, it’s a good thing. It’s a good thing for everybody, and the more we do it — maybe that stands to make us happier, and better. And so doing that I think has this, you know, very gratifying side to it. I could say a lot more about that, but I think at the very least, I think it’s just — it’s very gratifying to do and it’s … also, you know, I’m a total geek. I love computers. I think from just watching like, I remember seeing the first video game. I think I was 7 years old, and I was in an arcade in like Beijing. I was like — from the first time I saw a video game, and I still remember just how bright the pixels looked and I was mesmerized. From there I think it was just — there was something about the computer as a medium itself that I just love to geek out about, but then to really kind of try to understand it as a medium, and to work with it, day-in, day-out, whether it’s software, whether it’s hardware, whether it’s really interaction, interaction design, or whether it’s designing tools or games. I think it’s become something of an art for me because this is my medium, and I think I appreciate it kind of as this kind of medium for shaping things.

AW: What can we expect next from Ge Wang going forward?

GW: Ooh. That’s a good question. So, currently my students and I at Stanford — and we’re at the Center for Computer Research and Music Acoustics, or CCRMA — we’re exploring among other things, the possibilities of virtual reality and augmented reality for music in a way. The medium is completely different. It needs to be approached that way, but we’re also figuring out what things translate from kind of a — this having built instruments and tools in other mediums with the computer, in what ways do they translate and which ways do they not translate when we design instruments in VR, and what does it mean to perform together in VR? And what does it mean to go to — well to even attend a performance in VR? Is that even a thing you would do or is it just participatory kind of by default? So, I think there are a lot of questions around VR. Most of it, well, I would say some of it come from kind of an apprehension or a fear that VR is this medium that’s going to, just take over and is that — in what ways is that good for us? In what ways is that not, but also this curiosity of like, oh, what new possibilities for music-making lie in this new medium?

AW: Well, that sounds super exciting. Really looking forward to seeing what comes up with you next, Ge, and I just want to say, thanks again for your time today. It’s been so awesome talking to you, and I really appreciate you coming down to Princeton to talk more about your work.

GW: Thank you, Allie. Thanks for having me. It’s wonderful to be back.

AW: This interview was recorded at Princeton’s Broadcast Studio, with help from Daniel Kearns, and the music is licensed from FirstCom.com. And if you’ve enjoyed this podcast, we invite you to subscribe to Princeton Alumni Weekly podcasts in iTunes. We’ll be publishing more interviews all year long.

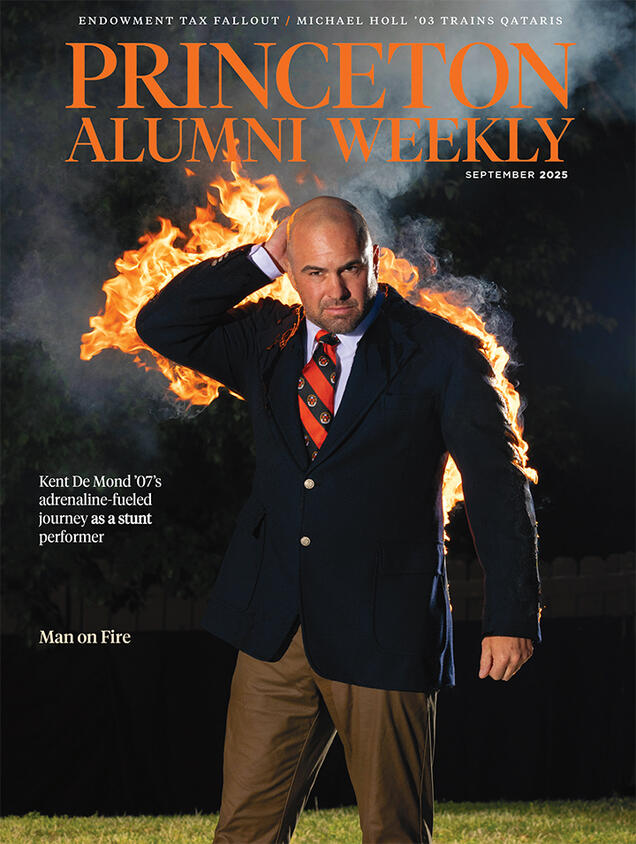

Paw in print

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet