PAWcast: Sociologist Danielle Lindemann ’02 on Commuter Spouses

Behind the trend of spouses living apart to pursue their careers

Inspired in part by personal experience, sociologist Danielle Lindemann ’02 studied the growing phenomenon of “commuter spouses” — couples who choose to live apart to enable both partners to pursue their career goals. In an interview with PAW’s Carrie Compton, Lindemann explains that the couples she spoke with for her book, Commuter Spouses: New Families in a Changing World, chose this lifestyle out of professional necessity, not for purely financial reasons. She also discusses what’s changed (and what hasn’t) in how we think about gender roles and how, paradoxically, high levels of education may tend to limit one’s professional choices.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Carrie Compton: Hi and welcome to the PAWcast, Princeton Alumni Weekly’s monthly podcast. I’m Carrie Compton and today I’m here with sociologist Danielle Lindemann, Class of 2002. Danielle is a sociology professor at Lehigh University who has just written a new book called Commuter Spouses: New Families in a Changing World, which unpacks the multiple factors that go into two spouses choosing to live apart, to pursue their individual careers: a trend that is on the rise in the United States. Danielle’s work focuses on gender, sexuality, and culture, especially as they relate to occupations. Danielle, thank you so much for joining me today.

Danielle Lindemann: Thanks so much for having me! I’m excited to be here.

CC: So, let’s start with a bit of your biography. You write yourself into the book, minimally, and for few years you were also a commuter spouse. So, tell us about that time and whether that was how you came to write on this topic.

DL: Sure, so this sort of happened because I was at Columbia where I got my Ph.D., I was on the job market, which if you know anything about the academic job market, it’s very difficult to find a job, especially if you’re looking only in one geographic location, which accounts for a lot of these kind of commuter marriages. And I happened to get offered a postdoctoral position in Nashville, at Vanderbilt University. And at the time, my husband had just gotten partner in his law firm, we were living in Brooklyn, and I found it very interesting when I talked to, say, my advisers or other people in academia, they just assumed that I would take the position and we would just live apart for those two years of that postdoc, right? And, you know, I’m a scholar who’s very interested in what we call deviance — of non-normative behavior — and I thought, at the time, this is kind of interesting, we might think about living apart from one’s spouse as being deviant, as being not the norm, but it seemed like in academia that was the expectation that you would do that. So that’s what sort of first got me interested in the topic. So the book is a bit autoethnographic: I do kind of write myself in there in a way. But, yeah, that’s that really inspired me to do the research and write the book.

CC: So, in the book, you say that there’s sort of a lack of modern research on this topic. Talk about what kind of work had been done and what you learned about what’s happened since.

DL: So, there has been some research on the topic in the communications field: Sort of like strategies, communication strategies that spouses use when they’re living apart. So, I don’t want to sort of discount that. But in sociology there really hadn’t been very much written other than these two books from the 1980s, the early- and the mid-1980s. And what was sort of — I guess we can get into my findings in a little bit, but one of the things that was really interesting to me reading those books and then doing this research is that, yes, a lot has changed, just thinking about the technologies that the couples are able to use now. In those older books they talked about writing letters to each other or having to pay for long-distance phone calls. Here it’s just — these couples really could be in touch continuously, as many of them said, they were in constant contact. So a lot has changed, but some things haven’t changed since the time those books were written. So that was really interesting, too.

CC: What were some of the more surprising findings of yours that, right out of the gate, shocked you?

DL: I wouldn’t say it necessarily shocked me, but it was surprising to me that the way that people talked about gender aligned very strongly with the way people talk about gender in those 1980s books. This idea that we still have that maybe the wife should subsume her career to the husband’s. Women more often said they felt stigmatized for choosing to opt into these relationships. Women were much more likely to be the primary caretakers of young children in these relationships, which is sort of interesting, because of you think of these relationships, you might just assume that they’re completely gender-egalitarian, right? Because these are couples who are choosing to live apart for both the husband’s and the wife’s job. They were all heterosexual couples, I should say. I didn’t interview any same-sex couples. So they’re making that choice, which sort of goes against gender norms in some ways. But at the same time, they’re really solidifying gender norms in other ways. For instance, the fact that the women were the primary caretakers of children in almost every case. And oftentimes, those women felt like they were single mothers or single parents. So, we do have this societal expectation that women should do the majority of the caregiving and here that was really concretized in these relationships that we might otherwise think of as very egalitarian. And they were egalitarian in some ways. But in certain ways, ways that I don’t know if they were shocking, but somewhat surprising. Something else that somewhat surprised me was the fact that these couples spoke a lot about how entwined they were in each other’s lives, and a lot of it had to do with the availability of the technologies. A lot of them sort of mentioned that they were in touch constantly, or continuously. I asked them, you know, in what ways do you rely on your partner: Many of them said for everything, or in every way. And that was somewhat surprising to me because, sort of, one of the, sort of, theoretical levers into this project when I first started it: I was thinking about this idea that we’re moving toward more individualistic relationships; there’s a lot of literature on that: How we sort of used to think of marriage as more of this, sort of, collective unit and now we think about it more individualistically, even the idea that we should love our partner is a very contemporary Western idea. The idea that marriage should fulfill us personally. Right? So, we’re moving in, sort of, this direction of individualism, and we might expect these couples to be extreme iterations of that because they are choosing to live apart to fulfill their own career goals. And most of them are not doing it because they need the money, they’re not doing it because of financial necessity; they’re doing it because their careers fulfill them.

CC: Let’s take a moment and talk about your sample. Talk about your sample size. What kind of generalities you can give listeners about who you spoke to for this?

DL: Sure, so I interviewed 97 people who lived apart or had lived apart in the past, some or all of the time. And they had to live apart for their careers, for their dual professional careers. And they had to have a separate residence for that purpose. So, I used that so I wouldn’t have to make, kind of, ultimately arbitrary distinctions between who lives apart and who just travels a lot for work. And I wanted to focus on well-educated, professional couples. And now, throughout history and today couples live apart for all sorts of different reasons. Immigration, marital discord, incarceration — all sorts of different reasons. I’m — was specifically focused on these, kind of, these professional couples because it is somewhat of a contemporary phenomenon: this idea that these, sort of, dual-career, well-educated couples would live apart for the purpose of work. And I focused on married couples because I was, again, interested in, sort of, the institution of marriage and how our thoughts about that have changed. And again, I wanted to include same-sex couples, and I actually worked through my own network to try to include same-sex couples, but again I included marriage as a criterion for inclusion, and they have not historically had access to that civil benefit. So unfortunately, I wasn’t able to interview any of those couples. I think that would be a fascinating follow-up study, though.

CC: Yeah, absolutely. So, you mentioned that a lot of this was not financially driven. What does that say that we’re making these extreme sacrifices for professional identity?

DL: I mean, it certainly says something about professional identity, this idea that we’re so embedded. I mean, it’s almost ironic, in a way, that we ascend to these high levels of education, right? And we tend to think that high levels of education would improve our universe of choices as we see them, but actually, they shrank the universe of choices as these respondents saw them. Because if you’re trained in this highly specialized field and you feel like you need a job in that highly specialized field, right, if you’re a professor of 18th-century Russian teacups, then, right? You need to apply to the two Russian teacup jobs, right? And then, wherever they are, if it’s Boise, you go to Boise. And then if your husband, or partner, is also a professor of Russian teacups, right, then you’re probably not going to be in the same place. So, we tend to think of education as something that improves your sense of choice or your universe of choices, but that wasn’t necessarily how these couples saw it.

CC: So, how common is the arrangement? Especially as compared to the literature you found from the 1980s?

DL: You know, it’s — everyone asks that question. It’s hard to say. It’s hard to give an actual measure of how many people are really doing this. You can look at census data and look at how many people are living apart, but that won’t tell you why they’re living apart. So, they could be living apart for any reason like marital discord, all the other reasons I mentioned. There was an economist, Marta Murray-Close, who looked at census data, and she found that highly educated couples were significantly more likely than just college-educated couples to live apart. Which I think she kind of makes the strong argument that this is because of this, sort of, labor structures, right? And this sort of specialized training that we get, that we feel that we have to move geographically in order to have a job. So, I know this is unsatisfying answer for everyone. It’s hard to put a number on it and I know some people have and some people have tried, but everyone who studies this, I always say, agrees that it’s on the rise. Not just in the U.S., but also there’s a lot of research in Britain, too, that it’s on the rise and people living apart from their spouses is on the rise, but we can’t say definitively — give a number of how many Americans are living apart for this particular reason.

CC: I see, I see. So, you said that it’s becoming more socially acceptable. Is it more acceptable for a man versus a woman? Or, how is that nuanced?

DL: Right, I mean, I think it is becoming more socially acceptable if you look at sort of the percentage of my respondents who said they felt stigmatized, it was lower than the percentage of respondents who felt stigmatized in earlier studies, but certainly there was that gender component in there. And I’m not the only who has found that: These communication researchers have also found that women tend to perceive that there’s more of a stigma against them for living apart. And, you know, typically it comes from family members saying, “Why aren’t you following your husband?” Because there is this idea of the so-called “trailing spouse” who follows their partner where his or her, but typically his, career is located and that is a very gendered expectation. Trailing spouses are not always women, but they tend to be women more often. So, the stigma that respondents felt did tend to be gendered: Women tended to feel more of a burden, more of a stigma of the fact that they were living apart.

CC: Tell us about what your respondents had to stay about living apart: What were some of the pros and cons?

DL: So, it is interesting. I do want to say first of all, I talk a lot about the pros in the book. And — but right off the bat, I want to say that this wasn’t the ideal lifestyle for any of them. This was something they felt, it wasn’t because of financial necessity, but they felt it was because of professional necessity, right? They were not living apart because it was a lifestyle choice, they thought it suited them; there are couples who do that. This wasn’t that set of couples. So, yeah, they were living apart because of these professional reasons and all of them, who I interviewed, except for one person, were either back living with their spouse by the time I interviewed them or intended to do so in the future. Except for one who said she wasn’t sure. (laughter) Although her partner said that he did want to live together so —

CC: Did any of the marriages dissolve during your study?

DL: I didn’t interview anyone that was currently divorced from their partner. There was one couple, very interesting, who lived together. No, who lived apart, then they lived back together again, then they got divorced, and now they got remarried to each other and are living happily apart —

CC: Oh yeah, you write about them, yeah.

DL: Right. Yeah, and it seems like living apart might suit them better in some ways. Although even they said that they ultimately planned to live together again. So I do want to say when I talk about plusses and minuses, this is not a utopian arrangement for any of them, but that said, there were some plusses to this relationship. So, some people talked about how it actually improved their communication, paradoxically, because if you have to pick up a phone and call someone every night and talk about your day, you’re kind of forced to talk to each other. Whereas, if you’re in the same space all the time, you’re just, you know, sitting on the couch watching TV, eating dinner, whatever, you’re not necessarily forced, sort of, have that communication. Some people said it, sort of, gave their relationship spice or, it was a return to the excitement of dating when they, you know, visit each other they could explore that person’s city. I mean, I certainly, like, enjoyed when my husband would come visit me in Nashville, and we would go out and explore Nashville. Now we didn’t have any kids at the time which is a whole other element. So there’s that and, you know, the women though were, kind of, uniformly — other than the women with kids, I should say, were kind of more uniformly positive about it, about the fact that it gave them space and about the fact that it gave them time to themselves, which is something that’s again, very gendered, it’s something that women don’t necessarily always have. There’s a whole literature on, sort of, leisure time, and the fact that men tend to have more — there’s a leisure gap now. Men tend to have more free time. Women’s leisure time is shorter and it tends to be more often interrupted by the demands of unpaid work like childcare or domestic labor, right? Women still do more, significantly, around the house than men do. So, in a way, it was sort of, kind of, a hall pass from the demands of domestic femininity for some of these women.

CC: So that leisure gap closed when you separate the couples, almost?

DL: Well, I didn’t look at the amount of time that they spent, right, so I didn’t assess it.

CC: Sure, sure. But it felt that way?

DL: Yeah, it did feel that way. That was sort of a narrative that came up — and that actually surprised me, too, because again, you would expect these couples to be more gender-egalitarian than the average because they’re in these relationships. But the fact that even these couples were — the women were talking about, “Oh, I don’t have to pick up my husband’s shoes anymore.” Or, it gives me me-time, it gives me space, right? Where the men weren’t necessarily telling those — some men were, but in the aggregate they weren’t necessarily telling those same kind of narratives — I think is significant.

CC: So, what happens when children are involved?

DL: Right, so again when children are involved, the women tend to be primary caregivers of the children. So, about over a third of the couples I interviewed, I should say of the people I interviewed, had children under the age of 18 at the time they lived apart: about 37 percent.

CC: Oh wow.

DL: Right, in three of these cases, the children were living with the father. So, right, so overwhelmingly the children were living with the mothers and, as we talked about these women felt that — many of these women felt that this really, you know, intensified their, you know, their domestic demands. Well that makes sense, right? So, again, we might think of these as gender-egalitarian relationships, but it actually sort of crystallized these female gender role expectations in some of these couples because they were doing everything. It wasn’t just that women were doing more with the kids, which statistically is true in the aggregate, they were doing everything with the kids. Right? Because the men weren’t physically there. So, I thought that was kind of an interesting finding. It wasn’t surprising to me but that was something the writers from the 1980s also talked about and was reflected here as well. So that really hasn’t budged very much. And I also thought it was interesting in the instances, in the sort, of outlier instances where the men were the caregivers, the men knew it — they knew they were the outliers and one of them talked about how he, sort of, got praised for it. People said “You‘re doing this great thing!” And his wife said, “You know, I don’t think I would get praise.” And, of course, I don’t think any of the women I talked to who were the primary caregivers were getting this, “You’re doing a great thing, you’re really doing something wonderful for the family here,” right? So that was very gendered as well.

CC: Time zones complicated things as well. Right?

DL: So, yeah, that’s something that people often ask, is how did it vary based on how far people lived apart. The people who lived closer together seemed to sort of — I didn’t measure happiness, but they did seem to be, sort of, more content. If you’re seeing your partner two days out of every week, it’s very different from if you’re seeing your partner every few months and you live 12 hours apart and you know, you can’t even really pick up the phone to call them because they’re asleep. That’s a whole other, sort of, can of worms, I guess.

CC: So, talk about technology and what technologies they tended to use. Your research was just a little bit before Facetime, is that correct?

DL: So, Facetime was around and one of the things I thought — and Skype was around, obviously. One of the things that I thought was interesting is that they had access — it wasn’t that they didn’t have access to it. Right? Because, again, these are sort of people working in white-collar jobs, right? They’re sitting at desks; they can use this technology. But, most of them said the phone was their most important form of communication, even though they had access to Facetime. And, sort of, they talked about the sort of, especially with Skype, they talked about it freezing and things like that, right? And sort of the snafus, but it’s interesting because a lot of this work from the 1980s talks about the, sort of, lack of face-to-face communication and how, you know, that really negatively impacted their relationships. But here they had the ability to communicate face-to-face, theoretically, but they’re not really — I mean they used it, right, they certainly used it, but the phone was more important. But I think it would be interesting to see how those technologies progress and as they become better, are they going to become more important to these couples?

CC: You also talk about, kind of, the different buckets: People used text for, kind of, more casual: hello, whatever, and email for more administrative tasks.

DL: Right, I thought that was really interesting, too: the sort of constant communication they had via text. If they wanted to have a big emotional conversation: call on the phone. If it’s, like, you know, this guy is coming to fix your electricity, like, what are the things we need to deal with, right? Or, I’m planning my daughter’s wedding as one of them was. They were going back and forth about their daughter’s wedding. They would email each other. So they would have those details. But that’s one of the things that’s different about this study is that we have access now to all of these different, for better or worse, we have access to all these different buckets that didn’t exist in these earlier studies.

CC: Toward the end of your book you have this quote that I really liked. You said that “the emergence of the commuter spouses reveals something about our broader incompatibility between the traditional notion of family and the changing structure and meaning of professional work.” So, riff on that for me. What do you think that is?

DL: Right, I mean, so, it’s hard to use the word traditional, I mean, tradition of what? Right? But I guess when people think of traditional, they might think of, sort of, the 1950s, right? Which was a weird time in our country’s history. It wasn’t really traditional, but I think that’s the reference point people tend to use. And so, take academic jobs, for instance, right. They were work fine if you have a man who is able to travel anywhere, and again we’re looking at heterosexual couples, has a stay-at-home wife who will travel with him and she’s portable. So that works, right? Until, then the wife gets educated, too, and also has professional aspirations and then that doesn’t really work so well anymore. And more and more we’re seeing that as women are, you know, going to college in higher numbers, and going into higher education beyond college in higher numbers, right? Now we see this highly educated workforce of professional women who now have their own aspirations and they aren’t just going to just, sort of, be portable. And there’s a tension there.

CC: Yes, that’s interesting. So, thank you very much for joining me today, Danielle. I really appreciate you making the trip out here.

DL: Thanks so much for having me. It was really fun.

Paw in print

November 2024

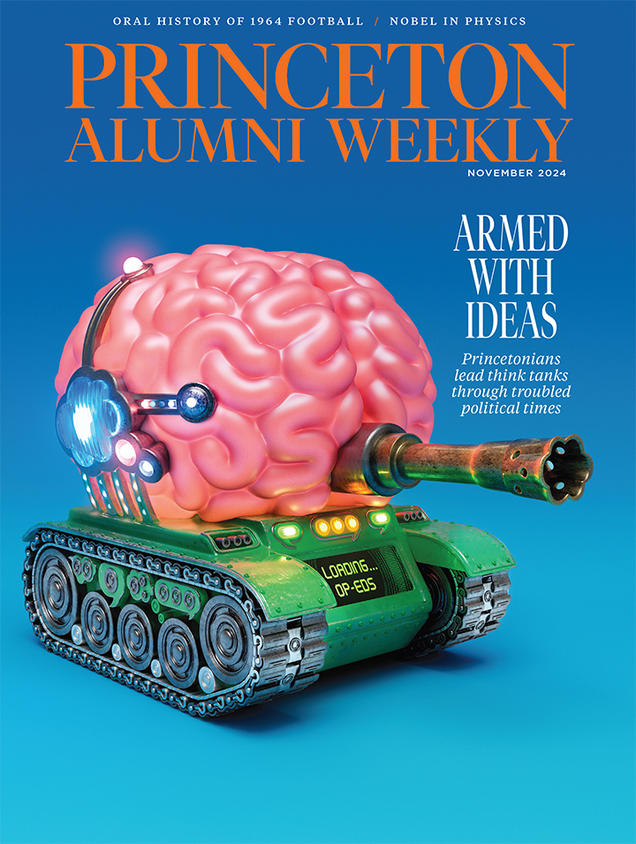

Princetonians lead think tanks; the perfect football season of 1964; Nobel in physics.