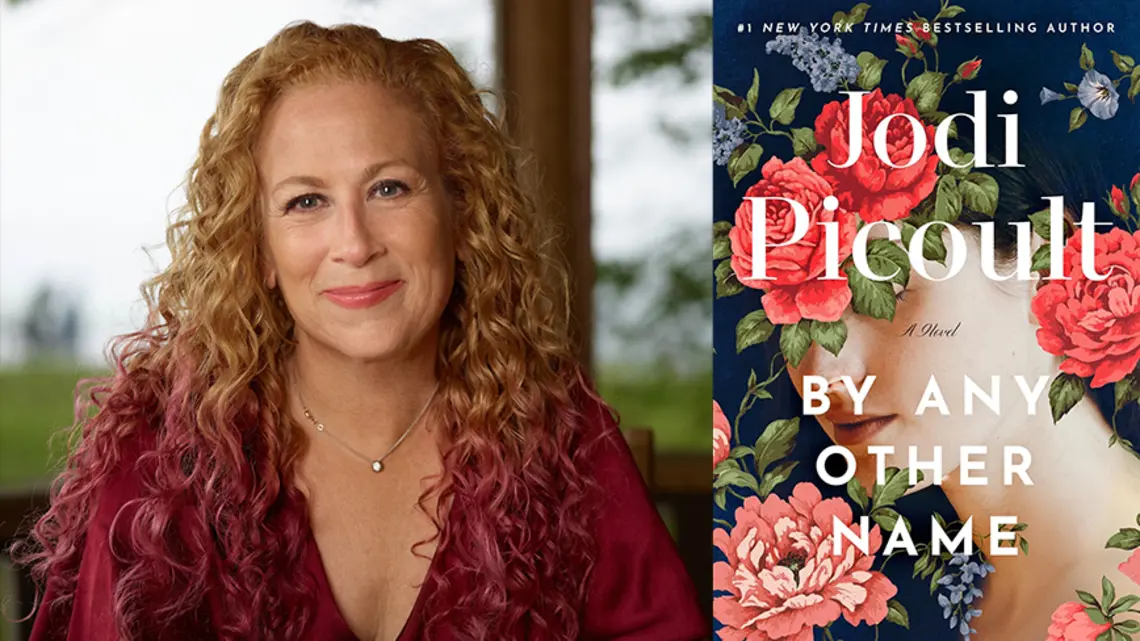

‘By Any Other Name’ by Jodi Picoult ’87

‘I never set about to write this story because I wanted to take down Shakespeare. I did it because I love those plays, and I wanted to understand how they could have come to be’

On this episode of PAW’s Book Club podcast, we ask bestselling author and playwright Jodi Picoult ’87 about her latest book, “By Any Other Name,” which presents readers with a hypothesis: Could Emilia Bassano, a woman who really lived in Tudor England, have written some of the most famous plays attributed to William Shakespeare? Picoult discusses why she believes it, how her book has been received by scholars and fans, and the experiences she’s personally had with the persistent misogyny in the theater world.

Join the PAW Book Club here, and get started on our next read.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is PAW’s Book Club podcast, where Princeton alumni read a book together.

Today, I’m very excited to interview author and playwright Jodi Picoult, from Princeton’s Class of 1987 about By Any Other Name, her latest in a long line of bestselling novels. In her note at the book’s end, she writes that she fully expects hate mail for this one. Why? She dares to question the authorship of one William Shakespeare.

Her book introduces us to Emilia Bassano, a woman who really lived in Tudor England, published her own poetry, and could plausibly have written some of Shakespeare’s most famous works. A parallel, modern, fully fictional story runs through By Any Other Name as well, suggesting that misogyny in the theater world might not have abated as much as you’d expect since the 1500s.

Jodi, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us.

Jodi Picoult: My pleasure.

LD: We got a really great response from our PAW Book Club members, so I’m excited to start asking you their questions. I’m going to begin with some about Shakespeare’s authorship, which I think just really captivated everyone.

First up, Michael Behrman from your class of ’87 writes, “This is fun. Mary Ann Evans (that’s George Eliot) did it. What brought Jodi to think about this? Could a man have written the Shakespeare female characters as well as a woman?”

JP: It’s interesting that he brings that up, because that’s very much the reason that I kind of fell into this rabbit hole. I actually took all my Shakespeare classes with Professor Michael Cadden at Princeton, loved them. What did I love about Shakespeare? I loved the beauty of the writing in the plays, but I also loved the characterization of the females. Nobody else was writing women like that. You had these incredibly complex, three-dimensional characters like Portia, and Kate, and Rosalind, and Beatrice, and I thought there was nothing else like it at the time.

I think Michael Cadden said to us once, for maybe four seconds of a seminar, that there was a question about Shakespeare’s authorship. Honestly, I was like, “Oh, yeah, okay, whatever,” but I was a good little English major and I laughed it all off. I didn’t think about it for years until I read an article in The Atlantic by a woman named Elizabeth Winkler (’11). In it, she mentioned something that just stopped me in my tracks, which was that Shakespeare had two daughters that survived infancy, and he taught neither of them to read or write.

I was like, “Yeah, no, I just don’t buy it.” I don’t believe that the same person who created those incredibly complex female characters in the plays would not have taught his own daughters to read or write. It made me fall into, as I said, this rabbit hole about authorship, and about what we actually know, the actual facts that we have about Shakespeare, who he was, and what, if anything, he wrote.

I had never heard of Emilia Bassano. I had heard lots of authorship stories before. I’d heard about the Earl of Oxford being the forerunner of the anti-Stratfordian movement, but I had never heard a woman’s name mentioned. When I started to learn more about Emilia Bassano, I couldn’t believe how seamlessly her life plugged in all of the question marks and gaps that exist in Shakespeare’s that allow us to wonder if he actually wrote these works.

LD: Sue Rhoades *92, asks, “Your novels often take on difficult and uncomfortable subjects.” Sue also saw your note about expecting hate mail and antagonism to be off the charts, as you said for this one, and asks, “Has it been? Is there any particular area of criticism that has surprised you?”

JP: Yeah, so I interestingly was getting pushback for this book before it was even published, which blew me away. I did an event at the Hay Festival in England, and I had some guy, some older academic white male, who wrote a piece and published it about how I am a crackpot conspiracy theorist. All I could think was, you haven’t even read the book. How could you know? That kind of continued after the book was published. Every criticism that I have received has been from someone in academia who has studied Shakespeare, most are men, there was one woman.

Look, I get it. When you have crafted an entire career and persona around studying Shakespeare, it’s scary to think that maybe what you’ve learned all those years, what you’ve upheld all those years, may not be accurate or true. Interestingly, I think questioning Shakespeare’s authorship doesn’t take away from the plays in any way. I think it brings more people to them. The reality is I have heard from far more people who’ve said to me, “I never really got into Shakespeare. I didn’t understand it, but man, now after this, I’m reading it again, and it suddenly makes sense,” which I think is really interesting.

But I will point out that the academics who have written me and have all called me a conspiracy theorist and told me I’m ridiculous, also have all said, “I did not read your book and I will not read your book.” I can’t really take that criticism seriously. If you want to attack me, by all means, criticize me, but do it after you’ve actually read my book, and you’ve seen all the research that I’ve pulled together.

LD: You mentioned some of the other theories about Shakespeare’s authorship, and not surprisingly, we got a few people who said, “Well, what about this one?” Rick Ober ’65 asked about Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, noting, as Rick noted, that he himself got a 93 on a high school paper he wrote about the Earl of Oxford in 1960, so congrats, Rick.

And Karen Eschenlauer Macrae ’81 asked about Michael Blanding’s 2021 book North by Shakespeare, which looks at the possibility Shakespeare adapted his plays from ones previously written by Sir Thomas North, for his patron, Robert Dudley, who was trying to woo Queen Elizabeth. That’s a lot. Have you heard of these? What did you think of them?

JP: Yeah, I’m not as familiar with the North controversy or I haven’t read that book, but I do know of it. There are lots of others that have been floated, including Christopher Marlowe, and of course, Francis Bacon, and even Queen Elizabeth herself. Mary Sidney. They’ve all been suggested as potential authors.

In reality, based on everything that I dug up when I was researching this book, I think that Alexander Waugh was probably the closest, he was the one who came up with the idea that there was a stable of authors, kind of like James Patterson has now, where there’s one person giving out ideas, but lots of different authors are writing the books. I think that was what was happening. I think that Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, was the ringleader. I think he was the one who was sort of corralling all of these different authors.

I didn’t really go into it in the book, because this was a story about Emilia that I wanted to tell. I do not believe that Emilia wrote all of the plays, either. I think she only wrote several of them, based on the places I so heavily see her fingerprints in the plays. I think that de Vere probably wrote most of the history plays, for example. I know that there are other, Two Noble Kinsmen, I believe is one of the plays that they now believe that Shakespeare or whoever it was, was collaborating with somebody else on.

There are other plays where we know, for example, that there are pieces of Macbeth that were added by Middleton that were not in the original, that were crafted by Shakespeare or whoever actually wrote the play. We know that there was definitely collaboration happening. That in itself is worth pointing out, because the diehard Stratfordians have said for years, “No, no, no, Shakespeare wrote all of these himself.” That in and of itself is the most ridiculous elitist statement, because there was not a single other playwright of the time who was doing that.

They always had their hands in each other’s work, because the plays were owned by the theater companies and the producers. If, for example, you wanted to bring back a version of Hamlet, but you had this hot actor that you really wanted to spotlight, you would just hire any old playwright to add lines, or take away lines, or make changes to accommodate what you wanted to showcase in that season. Nobody was precious. There weren’t copyrights. The idea of a folio didn’t even exist until Ben Jonson did it.

This thought of Shakespeare never working with anyone else is such hubris to me. Yeah, I guess I would say yes, I absolutely believe that there were lots of people who were using the name William Shakespeare. Again, the reason that tracks for me is because although we have proof, literal proof that Shakespeare was an actor, and he was a producer, and he was a businessman, we do not have any actual proof of him writing a play. The only handwriting we have of his on a play was a play that was written by somebody else that was found after his death.

There’s nothing else that suggests that a play with the name William Shakespeare on it was actually written by William Shakespeare. In fact, I think there’s more evidence to the contrary.

LD: Shani Moore ’02 wrote, “A fantastic read from one of my fave authors, thank you!” She says, “There’s also been speculation that Shakespeare was Black or part Black. Did you encounter this in your research?”

JP: Absolutely not. I did not find any mention of that whatsoever.

LD: Interesting.

JP: That’s news to me. But I do know that there are questions, of course, around his, or whoever was the playwright, the portrayal of characters like Othello. I have a terrific professor named Alicia Andrusky who works at William & Mary, who did an interview with me, and who runs an entire course on Shakespeare and Black theater. I know there’s a lot in it now. There are a lot of academic questions about that, and about queer theater, and how that intersects with the plays, but I did not uncover any of that myself.

LD: Oh, interesting. OK. Linda Morgan *93, writes, “Happy to see your book displayed in the gift shop at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C.”

JP: What?

LD: Yeah, that’s cool. “Will the library be making any changes to their exhibits and academic content as a result of your book?” That’s interesting.

JP: Man, I wish I had that kind of clout. I didn’t even know it was at the Folger Library. How lovely, actually, that was in the gift shop there. That makes me feel very happy. I think I’m fighting an uphill battle, if that’s the way I can put it. I believe that one of the reasons that academics have been so rattled by this book and by the thought that I decided to tackle this is because a lot more people read popular fiction than read academic discourse.

I know for a fact that legions of readers who might never have thought about the authorship controversy are now walking around going, “Did he write that stuff?” That’s scary. That’s like anarchy to them. I don’t imagine that the Folger Shakespeare Library or, say, any place in Stratford will be championing Emilia Bassano’s name anytime soon, but that’s not to say that sowing the seed of doubt isn’t important and doesn’t matter. That’s how you start.

I think just asking questions to me is the root of real academia, right? And constantly making sure that if there’s something more to learn, you’re uncovering that stone. That to me is why this was so interesting. I never set about to write this story because I wanted to take down Shakespeare. I did it because I love those plays, and I wanted to understand how they could have come to be.

LD: Now, I have a whole bunch of questions on the story itself and how you put it together. Judy Lee, who’s actually the parent of an undergraduate here, asks, “How can we explain or understand the resiliency of Emilia and other women like her who endured so much? What can we learn from it?”

JP: Well, I think what we learned is that a lot has changed for women in 400 years, and an awful lot has not. That was kind of the thread that I wanted to sew through the entire book. It’s the reason that we have Melina’s story in there too, as you pointed out, the modern day equivalent in theater.

There are things about Emilia that were extraordinary, where she had a couple of moments in her life where things happened to her that gave her opportunities that I think most women did not have. She was not nobility. She was an immigrant. She was Jewish and had to hide her faith. At age seven, after her dad died, she wound up becoming the ward of the Countess of Kent. The Countess of Kent was, she’s a real MVP in Emilia’s life, because she educates Emilia, she gives her a full classical education, and a legal education. Both of them are incredibly rare, even for a noble daughter to have that kind of education, but here’s little Emilia who suddenly has a working brain.

That I think is a blessing and a curse when you’re a woman in Elizabethan society, because you obviously are owned by your father, and then by your husband. You are expected to produce children, and that’s basically the sum of your life. When your mind is sparking, and your mind is equally or more, as important or more important than your body, what do you do with that fire? I think that’s what made Emilia so interesting to me, that fire.

The other thing that happened to her was at age 13, she becomes the mistress of the Lord Chamberlain of England. Lord Hunsdon, I actually think he treated her relatively well, because all the information we have from Emilia, which comes from the diary of Simon Forman, this hack astrologer/doctor that she went to at one point in her life, all of that suggests very clearly in her voice that she was quite proud of the tenure she spent as his mistress.

She was treated well. She was given money and jewels and told she was beautiful by many people in court. We also know that she was very upfront about how much she hated her husband when she met with this guy. I think she was not afraid to sort of speak her mind, but again, that was pretty rare for a woman of the time.

For me, you have someone like Emilia who has a brain, who is really, her body becomes a transaction for her for 10 years when she’s a mistress, but I don’t think she’s willing to let go of her brain. I believe that, again, someone who publishes the first book of poetry by a female ever in England in 1611 in her 40s does not appear out of thin air. She probably was writing before that and was writing under someone else’s name, or was in some way hiding what she was doing. For all of those reasons, I feel like there’s a resiliency to her where she didn’t give up. We know for a fact, because again, this is part of her actual history, that every time her husband blew through all of her money, or decided to go off and try to become a knight, she would reinvent herself to keep her family alive and afloat.

She did all kinds of things, from writing, to running a school for the daughters of a gentry who were caught in between classes like her to educate women. She was constantly trying to find a way to survive. She represented herself in court twice against her brothers-in-law who were stealing money that was owed to her. All of these things are not typical for a woman of the time. That spirit, that spunk, I think, for Emilia is what makes her so interesting to me, and probably what made life so frustrating to her at the time.

LD: You mentioned her body as transaction. It’s so interesting, because around the office, we actually had some conversations about how graphic and unsettling many of the scenes in the book are, particularly the sexual violence with her husband, and the scenes with that Lord Chamberlain, when Emilia was just 13. Why did you decide to include these and write them in this way?

JP: Well, because it’s reality. I was on book tour for literally three months for this book, and every time I mentioned that Emilia became this mistress at age 13 for a man who was 56, without fail, the entire audience would go, “Ugh,” and yes, that is the correct response. At the time, that was really normal. It was very, very normal for older men to take young women as brides, because it was all about producing an heir, and because people died in childbirth very often.

I feel like I wasn’t going to shy away from the reality of her life and the brutality of her life, and the fact that although we don’t have proof that Emilia was physically abused by her husband, I know she hated him and I know it was certainly not a love match. She was forced into the marriage, and she was very clear about the fact that she did not enjoy her marriage. I don’t think it’s too far of a stretch to assume that it was not a great relationship, and potentially pretty abusive, because she was, at the time, owned. That’s what a woman was. You were owned.

I think it’s interesting that you talk about 13, because one of the plays that I do think she wrote was Romeo and Juliet. One of the reasons I think that is because it is the only Shakespearean play where the age of the heroine is mentioned. It’s mentioned three times. Juliet is 13, and every time it’s brought up, it is brought up in conjunction with whether or not she is ready to have a sexual relationship as a wife, which I don’t think Shakespeare cared too much about, but I know Emilia did.

LD: Oh, that’s so interesting. Marcia Weinstein Steinbrook ’74 asked, “Why doesn’t Emilia Bassano pass down Jewish ritual practices, even if they must be done secretly, to her son or to her grandchildren?”

JP: I actually assume that she did. I would think that very much like she would have celebrated the Sabbath on her own privately, or the way that candlesticks were hidden in her cousin’s house, I think the same thing would’ve happened for her and her family as well. But that was a death sentence. It wasn’t like you were going to be talking about how proud you were to be Jewish at the time.

I think there is a scene in there, if I remember right, where she explains to Henry when he’s young, how you tear your lapel to show honor and grief for the dead. There’s a hint of it, I think, in there.

LD: It’s hard to fit everything in a real person’s life, into a book.

JP: It was already a very long book.

LD: Jeff McCollum ’66 asked, “Have you learned anything about Emilia since finishing the book?”

JP: Well, I’ve had a couple of things happen that are incredible. The first thing that I talk about in the author’s note is when I went to go see Emilia’s portrait, this miniature that was at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Keep in mind, this is a work of fiction. Emilia had such a sad and terrible life. She outlived everyone she ever loved, and it was a hard life. I wanted to give her some joy.

And so I created this relationship with the Earl of Southampton. I did it because of a factual primary document that talks about when Emilia was in her 50s, and I said she took herself to court to represent herself against her brothers-in-law. Again, this is all very weird for the time, but even weirder was at the end of this one trial, out of nowhere, the Earl of Southampton appears. He walks into basically the justice, the magistrate, and says, “This isn’t my court, but if it was, I’d sure find in her favor.”

I was like, “What just happened?” There’s no world in class society in England in Elizabethan times where the very titled, very wealthy, very famous Earl of Southampton is just going to walk in to intervene in the trial of a commoner. Then I thought, OK, did they know each other? I realized that for the 10 years that they were at court, yeah, they would’ve, and they were roughly the same age. She was about three and a half years older than he was.

Then I started to see all of these very interesting threads, like the very first poems that have William Shakespeare’s name on them are these long form poems, with very lengthy erotic prefaces to the Earl of Southampton who had dedicated to, which is one of the reasons people think that he was bisexual, Shakespeare, unless of course, Emilia Bassano was just writing them to her lover.

Anyway, I create this whole relationship, and then I finish the book, go to the Victoria and Albert Museum, and I’m looking at this Nicholas Hilliard miniature of Emilia, and next to her is another miniature of a man with piercing blue eyes and long wavy red hair. I said to the archivist, “Who is this?” They said, “Oh, we don’t know. That’s an unknown man.” And I was like, “I think I might know.” I pull up on my phone, a picture of the Earl of Southampton that was painted four years later by the exact same artist.

The resemblance is very striking. The unknown man in the Victoria and Albert Museum is painted on the back of a playing card. The playing card was the six of hearts, which at the time in cartomancy, which was kind of like Elizabethan tarot, suggested that it was a soulmate card. This is the person I’m meant to be with that I can’t be with because of fate. The accredited Southampton portrait that I showed them from four years later was painted on the three of hearts, which says, “Someone has entered our relationship who’s breaking us apart.” In my book, that was her husband.

I show all this to them and they’re like, “What?” They wound up doing a very deep dive, and deciding based on the provenance, that it very well could be the Earl of Southampton. I feel like I kind of discovered that at the V&A, and I’m really proud of myself. That was one thing that was extraordinary. Here I was, creating what I thought was a fictional relationship, and the more stones I uncovered, the more I really think it could have been real, which was very weird as a writer.

The other thing that’s happened recently is I had an email from a fan who read the book who is a descendant of Emilia Bassano, and she thanked me for writing this book because she learned so much about her ancestor. I wrote her back and I was like, “Oh, my gosh, I am so jealous. I wish that I could be her descendant.” She was like, “You know what? On behalf of me and all my cousins, you are.” So I feel like I’ve been welcomed into the family.

I wish I knew more about Emilia, but the truth is that women’s lives were not recorded because they were not considered important. What we actually physically know about Emilia is located in a handful of primary documents. I don’t know that we’ll ever recover any more about her, but God, I would love it if we did.

LD: On the other story that runs through about Melina Green, the modern storyline, Stacey Bachrach ’77, asked, “You express so vigorously Melina’s frustration with gender bias, specifically in the field of writing. I wonder if you faced the same challenge much in your life,” at Princeton maybe?

Related, Ana Lopez ’76, asked, “As a writer, do you believe that women are systematically dismissed in theater today or by publishers?” I was curious about that myself. Have you encountered this misogyny? You’ve had your own plays produced, right?

JP: Yes, and I have encountered misogyny both in theater and in publishing, and I still do, which is pretty remarkable, actually. People are always shocked to hear that, that you can be a bestseller but still be marginalized in some way. When I’m on book tour and I get on a plane, and I’m usually sitting next to a guy in a business suit, and if I’m typing, he’s like, “What do you do?” I say, “Oh, I’m a novelist. “Oh, do you write children’s books?” If I say no, they say, “Romance?”

The fact that in 2025, or 2024 last year, that there’s still this assumption that if women are writers, they’re writing in genres that are female-coded, is to me, shocking and disturbing. In theater, everything that Melina hears about her play, about her ancestor, who is, it’s a young girl’s coming of age story, that’s what her play is, is something I was told to my face when I was first trying to get Between the Lines to Broadway.

Between the Lines was the first show that I adapted. I have a writing partner named Tim McDonald, and I was working with Daryl Roth, who was a very famous producer. It is a coming of age story that I wrote with my daughter that used to be, it was a middle grade novel, and we kind of aged it up for theater. I was told repeatedly, “Oh, this story is too small. It’s too emotional. Nobody wants to see a girl’s coming of age on stage, on Broadway.”

Mind you, I was being told that the year that there were two boys’ coming of age stories playing next door to each other in the Broadway theaters. What’s really shocking is if you know that theater industry in New York, 80% of tickets are purchased by women. That suggests to me that there are a lot of people who might like to see a woman’s coming of age story. Where’s the hang-up? The hang-up is in the theater owners. They are a handful of mostly white old men who tend to put into their theaters stories that they identify with.

That is why we tend to believe, because they’re kind of creating, they’re the tastemakers. People who don’t know this, who don’t work in the industry, assume that the stories that are worthy of Broadway are a certain kind of story, when in reality, there are Black stories, brown stories, queer stories, people with stories with disabilities, and women’s stories that all deserve to be on Broadway and all have an audience waiting for them. But we are not there yet.

The other thing that happened with Between the Lines, which is kind of interesting, is that when we were writing it, my producer said, “I don’t want your name on the playbill as the writer of the show, because it was based on your book and it will look like a vanity project, and we won’t be able to get it to Broadway. We won’t get people to invest.” I was like, “OK,” because I didn’t know anything. I absolutely co-wrote that show. And then when we had an opening night off Broadway in 2022, my name was listed as a novelist. I was not listed as a librettist.

It was after the show closed that my co-writer went to his lawyer and said, “This is not right, it’s not fair,” and got my name on all the materials. Now that the show is actually licensed, and there are places performing it all over the country, I have to tell you that it feels really good to be recognized for the work that you did. In many ways, I kind of feel like I’ve lived Emilia’s story.

LD: That was 2022?

JP: Yeah.

LD: Wow. Holy cow. OK, well, and finally, we received a couple questions about your process as a writer. This is actually my last question here. We’re doing pretty well. Ann Mongoven ’84 and Shani Moore ’02 asked about your writing routine, whether and how you battle writer’s block, and how you researched this book.

JP: Yeah. I don’t believe in writer’s block. I’ve been very vocal about that. I think writer’s block is the luxury of time. I actually think back to my days at Princeton. You had writer’s block, you couldn’t write that essay that was due, until miraculously, it always cleared up the night before it was due, right? Suddenly, you were able to produce a draft.

I started writing professionally when I had a newborn, and then very quickly, two more kids. I was the primary caregiver and I was a novelist, and I would write anytime they were napping, or at nursery school, or not hitting each other over the head with a sippy cup. I got to the point where honestly, I wrote in 15 minute bursts, because that was all I had. When you do not have time, you don’t get writer’s block. You can always edit a bad page, but you cannot edit a blank page. That’s something that I’ve kind of lived by now for 35 years. Even if you don’t particularly feel like you’re being creative that day, write something. You can always fix it.

How did I do the research for this book? Interestingly, like I said, there are such limited amounts of primary source documents that they’re pretty easy to get your hands on, and to read, and to see yourself. Like Simon Forman’s diary is a really good example of that, because that has most of the information about Emilia in it. There are other people who’ve done histories of the Bassano family, and their family tree, and how they all became the court musicians for King Henry VIII, and then eventually for Elizabeth I, and then onto James I.

I was using other people’s research whenever I could. Then I did a lot of interviews with professors, and I tried really hard to talk to female Shakespeare scholars, because I really wanted to hear their take on this. Many of them were interested. I don’t think they bought what I was saying yet, but they were very interested. Some of them knew about Emilia, some did not, but many of them could help me sort of plug in the gaps that I wanted to fill in Shakespeare’s life that allowed me to really find room for Emilia as the, I think, the real writer.

They also were really helpful to me in sort of creating a world where there were so many women working in theater in Elizabethan times that we don’t talk about. There were female producers, there were females who were patrons, there were females who ran the literal box office, which that term, I love this, this is one of my favorite facts, came from the person outside the theater who held a wooden box, and that’s where you would put your penny to go inside to the theater.

There were women who did the costumes, so they were all over the theater. Why not women authors? If anything, that kind of feels a little bit like an oversight. They helped me really kind of craft that world and see that a little more three-dimensionally. They also were really instrumental in explaining to me how evidence of absence is not absence of evidence. The fact that we have not had a woman proposed until recently as a candidate for Shakespearean authorship has a lot less to do with the fact that women couldn’t write, and much more to do with the fact that men were the one keeping the records.

A great example of this is the idea of mother’s legacy notes, which I talk about in the novel as well. It was very common for women to write a letter to an unborn child, because you fully expected to die when you gave birth. You actually went out like Emilia does, and you bought your own shroud. If you survived, then you absolutely got rid of that letter. You burned it, because it was very bad juju. But they weren’t saved for that reason. The letters were basically all the wisdom that women wanted to pass onto their children if they weren’t there.

What that tells us is that the women who did know how to write understood that when you put something on paper, it is a legacy. When you put something on paper, it has importance, and it has gravitas, and it has lasting repercussions and wisdom, that writing was fundamental to them. Some of these female scholars are just now finding evidence of these letters women wrote, which again, I think, is more proof that women were involved in that time, in both writing and in ways that we don’t usually think of them being involved.

There was a lot of that. I also went to the Globe Theater, and I talked to their main historian, who, his name is Will Tosh. He was a lovely man, and he was so funny. I told him my whole story and he was like, “Aren’t you cute? How silly of you to think that.” But he was great, because he gave me so much, so many resources that I could comb through to learn about Shakespeare and to learn about the plays.

That was another whole sort of mental gymnastics for me was looking at the dates that the plays were allegedly written, the times that they were published, how they lined up with Emilia’s actual life, and whether or not I thought she was involved in the writing of certain ones based on how they fell in her life. That was kind of doing a big Jenga.

In fact, it was so immersive for me as a writer to, it felt like casting a magic spell, to create the Elizabethan world, and to put it on paper, and to hold Shakespeare’s life, Emilia’s life, Southampton’s life, all of those details in my head, that I found it too hard to keep splitting back and forth between modern day and Elizabethan times.

So I wound up writing the entirety of the Elizabethan story first, and then the modern story, and then I cut them together, which I’ve never done. Every other book I’ve ever written has been written exactly in the order that you read it. That for me was a whole new experience.

LD: We did have some people who noticed that this was very different in some ways than your past books. Did it feel different when you were writing it? Did it feel... No?

JP: It’s so funny. Sometimes, I hear all the time from readers, “Oh, this book is like nothing else you’ve ever written.” I also hear, “Oh, my God, it’s so formulaic.” I don’t know what... I can’t be both. I don’t think this book is particularly different from anything I’ve written. I think it is something controversial. I think it’s something that will entertain you as a reader and educate you. Those are what I aim to do when I sit down to write.

I have written historical fiction before too, I’ve just never gone this far back. It was a little bit, that was for me, the challenge. Literally, if you looked at my Google searches, did everyone have windowpanes in Elizabethan England? Things like that. Oh, actually, I had someone write me last week who is some kind of scholar in entomology, I think. She wanted me to know that there’s a scene where there’s a pun made on the fact that Emilia is dressed like a butterfly, and Queen Elizabeth is talking to her and they make a pun on the word monarc. And she goes, “Monarch butterflies weren’t found until the 1800s.” I was like, “OK, you win. I did not know that.” I can’t know everything, but I try.

LD: I would imagine that you’ve done quite a lot of research for other books, but it wasn’t as obvious as this one. You know what I mean? You read this book and you go, “Wow, she did a lot of research.” I bet for your other books, you’re also researching, it’s just more invisible to readers. Am I right?

JP: It’s very different. Yeah. It depends. When you do research on ghost hunting, it’s a little different than when you’re doing historical research. You’re striving for accuracy in both subjects, but it certainly is different because you can’t be, I guess, checked so quickly when you’re doing research on ghost hunting as you would if you’re doing research on Shakespeare’s life.

I will say that one of the most interesting days on my book tour was when I went to Stratford. I actually asked to go to Stratford on my British book tour because I was like, “Hey, in for a penny, in for a pound.” I was expecting pitchforks, and I did not get that. They were very quiet, very sort of stiff-lipped audience. As I was doing a signing after it and people were filing through to have books signed, I had so many people say to me, “I always kind of wondered about that.” And I have to say that that made me feel like validation.

If you can get the town that is basically like Shakespeare Disneyland to say, “OK, maybe you have a point,” then maybe I was doing something right.

LD: Oh, that’s awesome. Well, thank you so much, Jodi. This has been fantastic. Thank you so much for taking the time for this.

JP: Yeah, it was really fun. Thank you so much.

The PAW Book Club Podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode and sign up for the book club on our website paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

1 Response

Roger Stritmatter

9 Months AgoExploring the Authorship Question

Jodi Picoult deserves congratulations for having the courage to explore the Shakespeare question in her new novel. It’s a pity, however, that she could not have done a more thorough canvassing of the history of the question and written with a stronger fictional premise in mind. Since 1920 the evidence has continued to accumulate, most recently “in spades” that the real author of the plays was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Within the last two years, de Vere has been shown in two separate peer-reviewed articles, one published in England and the other in the United States (Critical Survey and the South Atlantic Review) to have been named as the real author by both Francis Meres and Ben Jonson, the two most important early witnesses to the traditional biography. These findings cap over a hundred years of steady accumulation of evidence identifying him as the author and showing in intimate detail how the psychological profile of the author as he gives it in his own plays matches the biography, experiences, and temperament of the literary earl who lost caste from his commitment to drama and the arts. It’s a more interesting story because it happens to true.