In this edition of our monthly history podcast, Gregg Lange ’70 surveys the Princeton campus during wartime, we look at just how much dirt was moved to make Lake Carnegie possible, and we talk about books, including the list of titles that Princeton’s president sent to soldiers serving in World War II.

The Goin’ Backstory podcast is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson, the digital editor of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Gregg Lange: And I am Gregg Lange, of the great class of 1970, also the Rally ’Round the Cannon columnist, who should really know better.

BT: Welcome to Goin’ Backstory, a monthly podcast about Princeton history. For the December 7th issue of PAW, Barksdale Maynard has written a feature story looking at the Princeton campus after Pearl Harbor, and how World War II transformed the University’s operations and the student experience. In Gregg’s recent Rally ’Round the Cannon column, he looks at the Battle of Princeton, coming up on its 240th anniversary, when the Princeton campus was literally part of the battlefield. So it seems like a natural opportunity for us to talk about the history of the campus in wartime. During each of America’s wars, what was going on on campus? And Gregg, you’ve done some research on that very question.

GL: Well of course the recollections of students in the various periods are such that you’re almost guaranteed to get some interesting stories anyway. The norm at Princeton is the state of the famous “Orange Bubble,” so when things aren’t that way, people do tend to remember.

The Revolution of course started things off pretty seriously — a little extremely — in that Nassau Hall was a grand total of 20 years old at the time — it was built in 1756 — and was effectively gutted inside, mainly, in 1777 by first the British Army, who took it over prior to the Battle of Princeton, and then after the Americans won the battle, they had troops bivouac there who probably did more damage to Nassau Hall than the British did. At any rate, it really wasn’t operating fully again for about 10 years or so. After that classes the first few years were all over town and even further afield than that.

The opposite was true in the Civil War, when first of all, the large contingent of Southern students at Princeton just walked out, effectively, early in the engagement, and very much to the sadness of everyone concerned — there was great hugging and crying and everything down at the old train station at the foot of Alexander Road prior to the leaving of the Southern students. And the number of Northerners as well continued to dwindle through the Civil War, as many of the students went off to serve. They could of course buy their way out of the service if they wanted to, and some of the families did, but generally it was more the infirm and very youngest students who remained on campus, and there were very, very few by the end of the Civil War. The university — the College — at that point was not in very healthy financial shape at all.

I was interested in checking back on things to see that the Spanish-American War was such a lively cause, albeit very short lived, in 1898, that there were volunteer battalions drilling on campus, very much off to the side of the normal college operations, very informally during the war. But of course as that ended very quickly, they quickly disbanded. But that was recalled then in World War I, when the War Department was really sort of making things up as they went along, first in preparation for possibly the U.S. joining the war, and then when we did, taking all sorts of volunteer groups in aviation, in naval training, and in various kinds of military drills, all of which had been going on on campus in bits and pieces, and then accelerated after the U.S. joined the war.

For World War II, I strongly encourage you to read Barksdale’s article, which is wonderful. Showed a completely changed the campus over to a military footing, for two very basic reasons: one, the campus, especially in terms of the sciences, had much to offer in that area, and accentuated those. They sped up the education of the undergrads who were there, who became fewer and fewer throughout the war, and additionally then took in military training units, simply to make ends meet. Princeton was running a serious deficit for a short period in the war, until it took in Naval V-12 units and other training groups, including — heaven help us — women, training in cartography during the Second World War.

Korea, again, somewhat similar to World War I was sort of short-lived to get everything cranked up and operating. But because of the draft laws at the time, there were a gigantic number of Princetonians in the ROTC units during Korea, more then and immediately thereafter than before or since.

Vietnam, again, is a very highly chronicled period in Princeton history. Very slow in starting in terms of student reaction at Princeton compared to other places around the country, but when it did, it became quite a serious and actually quite complex force having to do with political action as well as demonstrations. Various different attitudes toward the military, although there was a sort of a meager firebombing of the ROTC armory in the spring of 1970, following the American invasion of Cambodia, along with the campus strike and a number of other things going on at that time. What changed as a result of all of this, and which was the focal point of much of the Vietnam objections, was the draft, which first went to a lottery approach in late 1969, and then in 1973 was allowed to expire permanently —to date, at least, and which effectively has taken a lot of the direct effect of wars subsequently off the campuses, and I think it’s an interesting argument as to whether that’s a good thing, a bad thing, or quite a bit of both.

The subsequent military actions that the U.S. has been involved in — many of them, again, fairly brief — have had very little impact on the Princeton campus, or indeed many other campuses at all, and it has come around to the point where with the U.S. now having now been in a foreign war status for the better part of 14 years — by far the longest wartime period in American history — the effect on campus currently is still extremely minimal. As a matter of fact, I tripped across a little factoid the other day, which is something for everybody to think on, and that is that Barack Obama is the first American president ever to serve a full eight-year term, all of which was served in wartime. And that’s probably something for all of us to think about fairly seriously. It doesn’t affect the campus much today. There are, however, as you can also see in the new issue of PAW, 17 freshmen involved in the Naval and Army ROTC units, which is a high for quite a few — going quite a few years back. Very small numbers compared to what it was prior to Vietnam. The other issue that’s going on today of course is the complete lack of veterans as students on campus, which does indeed have an effect on the attitude or absence of attitude in the student body. There are a number of structural reasons why that’s true, but it’s exactly the opposite of the major effect of World War II, which was the GI Bill, which took huge numbers of veterans, and put them onto American college campuses, for a period after the war, which has had a great effect on America’s history and outlook on the world ever since that day, and still has an impact today.

BT: Gregg, you’ve — we’ve been doing these conversations for a long time. I think that might set a new record in terms of the amount of ground covered in a single spoken block. But it is a lot to think about, and it is a fascinating story of Princeton’s history and American history. And thank you for doing that survey.

GL: Well, I thank Barksdale profusely for his article. I also should’ve called people’s attention — talking about the Revolution — to the magnificent article from 1976 for the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Princeton, very, very meticulously describing the Battle of Princeton and how it played out and what its impact was on the world of that day that Brett’s been kind enough to pull out of the back issue and post online. Virginia Kays Creesy is the author, and she just did a magnificent, magnificent job with it. There’s also a fabulous sidebar, as if you needed anything else in it, having to do with the effect of the campaign and the battle itself on various local families in the Princeton area, some names of which you’re still very much aware, and exactly where they lived — where their houses were, and what the British did to them marching through one way and then marching through the other. Really fascinating stuff.

BT: Also in our most recent issue, the December 7 issue, John Weeren writes about the construction of Lake Carnegie, and Gregg has wondered aloud, “What percentage of alumni even know that it’s an artificial lake?” I can’t answer that of course, but I suspect that our listeners — our history-minded listeners — are somewhat familiar with the lake’s origins. It has produced some indelible images over the years, from Einstein and his sailboat to students skating on the ice. But Gregg, ever observant, noticed something about the picture that ran with the construction story. What was it that stood out to you?

GL: I will credit John, our veteran and extraordinarily-talented archivist — among his many other talents — as having picked out a wonderfully evocative picture of the time, of the crews constructing the lake — which was not just simply damming a couple creeks, by the way, it was just a gigantic excavation effort, which I think really very few people around do fully realize.

What struck me about it is, if you look at the picture, and I looked at it, and I looked at it, and I looked at it, and it’s got a lot of guys and a lot of planks — because the bottom land there where Lake Carnegie is now was pretty swampy in the best of times — and a lot of wheelbarrows. And that’s it. No big steam shovels, which would’ve been the order of the day — probably because they couldn’t — they were too heavy to be rolled into that area — you really don’t know, but it’s a very deep photo, and it goes on for hundreds of yards, and there’s nothing to be seen but planks and guys and wheelbarrows. And I thought to myself, “Well, who’s going to dig out” — and John came up with 270,000 yards — cubic yards — of material being moved. I thought, “That’s a lot of wheelbarrows.” And it is. It is 3.75 million wheelbarrows full of dirt. And I’m not going to say that they didn’t have steam shovels that they could’ve used in some areas of it. All I know is from that picture, which covers a lot of ground, that I don’t see anything except wheelbarrows. And if it was 3.75 million wheelbarrows, then hopefully Carnegie had his leftover cash invested in wheelbarrow businesses, because that’s where he would’ve made his money in 1906. Very, very fascinating, and I really don’t think people understand the extent of the work involved in doing what they did at that point — not to mention how ostentatious the whole project really was. [00:16:00] I mean, Wilson was dying to have Carnegie buildings. For all the different things Wilson wanted to do at this point, this was literally at the moment when Wilson is instituted the preceptorial program, and all of the university’s departments, and all of this stuff, and Carnegie wanted to build a lake because he hated football.

BT: And of course it does give rise to a wonderful rowing tradition at Princeton, and to this day the rowers absolutely love that lake. They love the generally flat water, they love the wonderful facilities that have since been built on the banks... It’s a special place. It’s a big part of campus. It’s hard to imagine Princeton without Lake Carnegie.

GL: It is indeed. I mean, it’s one of Princeton’s largest extracurricular activities of any sort — over and above being the largest extracurricular sports activity, which it is. There are well over 200 students involved in the varsity crew programs, and certainly they’re among the healthier people on campus, physically. We won’t talk about the issue of rowing madly backwards for a certain period of time every year — that’s a different question. But at any rate, physically, there’s nobody like rowers.

BT: I’d like to take a very brief break to read a message to our listeners:

Would you like to read more about Princetonians in the headlines? In PAW’s new weekly email newsletter, coming in January, we’ll be sharing the most interesting alumni news in one, easy-to-browse list. You can sign up by visiting paw.princeton.edu/email, or by clicking the “Alumni in the News” ad at the bottom of any page at PAW online.

OK. So we are back in this December edition of Goin’ Backstory. Gregg, I’ve always thought of the holidays as a great time for reading. When you’re the son of a teacher, like I am, you always get some books for Christmas. Well, for Christmas, 1943, the university sent out a list of books to the 1,300 Princetonians then in the military, and asked them to choose three, which were then sent to them, wherever they were around the world. The list is available on the PAW website, and I thought this would be an opportunity for us to highlight maybe a favorite book or two from that list. Gregg, would you like to begin?

GL: Absolutely. I’ll even throw in a little curveball at the beginning by telling the assembled listeners which was the favorite of those, which I had never known. I actually wrote a column on this a few years back, and I never realized there was a list published of how many people responded. But the favorite was the anthology of 14 mystery stories. So that was — it was about 50 percent more than any other individual choice of those. And I always think, “Well, I’m sure most of the Princeton alums picked out the 14 mystery stories, and then got two volumes of Shakespeare to go with it.” But of course, we won’t go into that piece. At any rate, I can tell you what I would recommend — and this is having participated in wartime overseas and sat around twiddling my thumbs and being rather desperate for any sort of change of mental venue — there is no better book on that list than Moby Dick. It really sounds trite. You cannot read Moby Dick and remain where you are. You have to be transported to somewhere else while you’re reading Moby Dick. There really are relatively few books like that in the world, at least that affect such a broad range of people, and I couldn’t do better than that, so I just decided not to. So Moby Dick’s my choice of the ones on the list. How about you?

BT: There were a few on the list that I was kind of surprised to see. Tortilla Flat — I love Steinbeck, but I don’t even think that’s one of the top three Steinbeck books, although he was still writing then. The one that jumped out to me was Walden. Thoreau — I, like many students, read parts of that in high school and then took a deeper dive in college, and reading Walden is fascinating and thought-provoking when you’re 18 or 19, and you have lazy spring afternoons to sit under a tree somewhere. I suspect it would be quite a bit different when you’re with a platoon that’s preparing for D-Day or any of the number of extraordinary things that these young men were preparing to do. But still, there are passages in Walden that will stay with you for days, and you can’t just not think through them. And that, for me, makes it an interesting book to have on hand when you’re in a situation like that.

GL: I think it’s similarly immersive. Maybe not in quite the same level of concrete —

BT: So, on a related note, we asked people — we asked readers — if Princeton were to do the same thing today, send books to the men and women on active duty, which books would you propose as options. And we unfortunately haven’t received much, if any, response on that question. But why don’t we get the ball rolling? Gregg, what would you recommend, if you were to redraft that list?

GL: Well I’ll you, this is fascinating, because — and we haven’t discussed this — this is sort of an interesting carry over from both Tortilla Flat and from Walden, if you will. I thought a long time — especially about extremely current literature — and I went back to Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, which is one of the most unexpected, evocative books that you’ll ever see. If I really thought everyone in wartime was up to it, I would suggest Kerouac’s On the Road, but I don’t think everybody can handle that in a stressful situation. But you can handle Travels with Charley, and it is a magnificent evocation of the American mind. It really, really is. And of course there’s no better truly American writer in history than Steinbeck, which is essentially what you were saying. And I couldn’t come up with anything better than Travels with Charlie.

BT: Well that is funny, that’s one of my favorite books. I thought about lots of favorite authors — Kurt Vonnegut, Steinbeck, also, Kerouac, but I also thought about my job description, and the many, many alumni authors who would be worth thinking about for that list: Michael Lewis, Danielle Allen —

GL: Way to suck up, guy.

BT: But the one I would certainly want to see on this list is John McPhee, and the book that I would recommend — for no better reason than that I happen to be reading it right now — is Coming into the Country, his book about Alaska, which in my mind is really part of McPhee at his best. It has really wonderful stories about the place and the people, and it just creates a — well, to go back to what we were saying earlier — a very immersive reading experience, and I think that that’s McPhee at his best.

GL: And in terms of people who are writing today, it’s very hard to argue that there’s anyone out there of the quality of John McPhee on a year-in and year-out basis. Even ignoring the issue of his legendary status as a teacher, for those of you who want to hearken back to his initial book on Bill Bradley. He wrote an article on lacrosse a few years back that just left your mouth open, it had such poetry to it. The man has a feel for human activity, interaction, and emotion, and how it relates to the physical world that is just very, very hard to describe. And ironically, I think that ties very much into one reason why I’ve got such a weak spot for Travels with Charlie. It’s not The Grapes of Wrath, but it’s not supposed to be. But it’s a singular book that I think ironically is more John McPhee-like than anything else John Steinbeck ever wrote.

BT: Well, Gregg, happy reading over the holiday period, and we will be back with more to talk about in January.

GL: I hope everyone has magnificent holidays, as many as you can justify. I dragged out Festivus as part of my Rally ’Round the Cannon column this time around, and fully believe we all take advantage of the Festivus pole, in addition to everything else. So please have a wonderful holiday — look forward to seeing you next month.

BT: Goin’ Backstory is a podcast from the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

GL: Online.

Paw in print

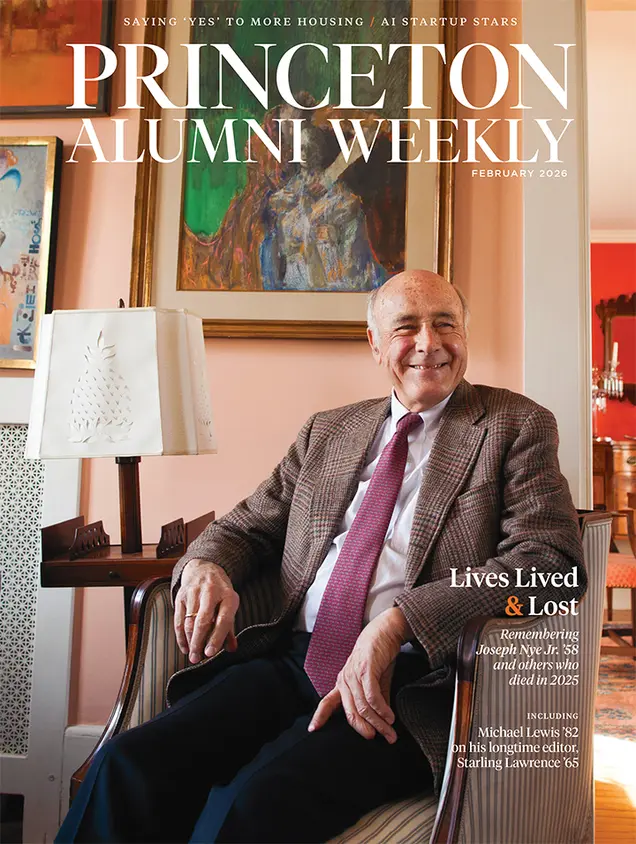

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet