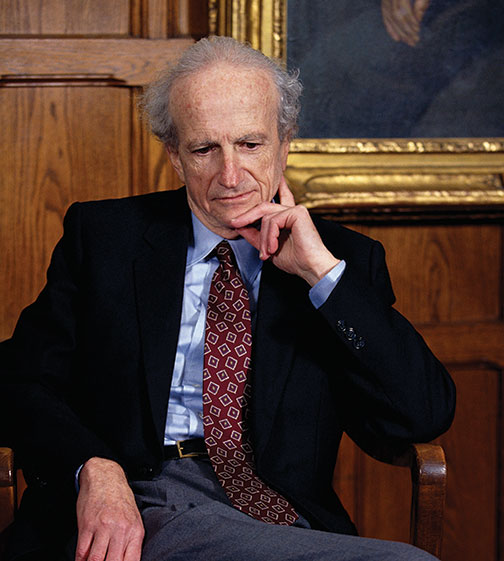

Lives: Gary Becker ’51

Gary Becker ’51

Gary Becker ’51

Before Gary Becker ’51, economists didn’t spend much time thinking about how economic methods could be used to study racial discrimination, or to predict how many children a couple might choose to have. But a Nobel Prize and a Presidential Medal of Freedom later, Becker — who died at 83 — had thoroughly changed the landscape of the economics profession.

In his 1957 book, The Economics of Discrimination, Becker explained how patterns of discrimination could outlast powerful market forces as long as people maintain their preferences for prejudice. In 1964, he published Human Capital, which explained how workers accumulate skills over the course of their careers, and at what cost.

In 1981, Becker published A Treatise on the Family, which argued that as women enter the workforce, their desire to have children declines because their time is suddenly more valuable. This means, Becker concluded, that the most effective way to reduce population growth is to provide girls with education — a view that “now informs development policy throughout the world,” says Stanford economist Edward P. Lazear.

Becker, who taught for decades at the University of Chicago, “pioneered the application of economics to fields that had traditionally been outside the purview of the discipline,” says Princeton economist Harvey S. Rosen. “At first, some of his ideas were met with resistance, and even ridicule. But today they are widely accepted by economists and have influenced the other social sciences as well.”

Edward Glaeser ’88, a Harvard economist and former teaching assistant for Becker, goes so far as to say that his mentor did “no more or less than redefine the field of economics.” President George W. Bush, in awarding the Medal of Freedom, called Becker one of the most influential economists of the last century.

Using an analysis of academic citations, Steven D. Levitt, the co-author of the economics blog Freakonomics, concluded that Becker was the most widely influential economic theorist of his time — by far. Becker’s record of publishing seminal papers since the 1950s until recently reflected “incredible longevity,” Levitt has written. Becker’s legacy can be seen in fields as far-flung as neuroeconomics and behavioral economics, and in popular media outlets. His restless mind sometimes led him to take heterodox positions, such as backing the legalization of marijuana, salaries for college athletes, and an end to the United States’ embargo on Cuba.

Becker was born into a small-business family in coal-country Pennsylvania. After graduating from Princeton, he earned his Ph.D. and taught at the University of Chicago as a disciple of the free-market thinker Milton Friedman. Except for an interlude at Columbia, he remained there for the rest of his life.

The “Chicago school” of which Becker was a part had a reputation as being aggressively, even irritatingly, competitive. But Glaeser says that while Becker was “not happy with sloppy reasoning,” he was “an extraordinarily decent and, in many cases, a gentle person. It was intellectual combat with chivalry.”

Becker remained active into his 80s, blogging and publishing papers. “While people 40 years his junior were dozing in seminars,” Lazear recalls, “Gary was always alert, intense, and involved.”

Louis Jacobson ’92 is deputy editor of PolitiFact and a state politics columnist for Governing.

Friends, colleagues, and family members pay tribute to Nobel Prize-winning economist in a ceremony at the University of Chicago, where Becker was a faculty member for 46 years.