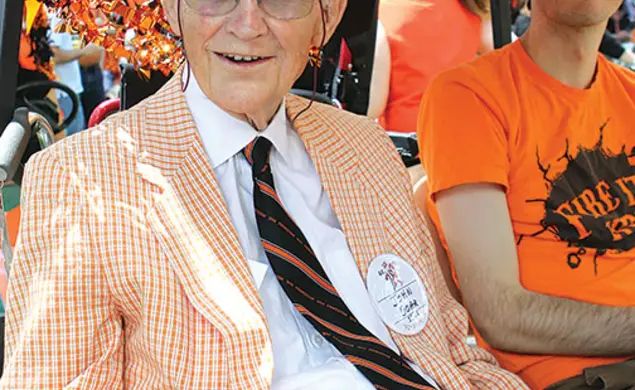

Lives: John Doar ’44

Lives-Doar317new.jpg

Lives-Doar317new.jpgJohn Doar ’44 enjoyed a life punctuated by surprising turns and ironic twists. A Midwesterner born in the “Deep North” city of Minneapolis, he spent his most exciting and challenging years in the Deep South. One of the most distinguished lawyers of his generation, he won his greatest victories outside the courtroom. A Republican in his early years, he became a key figure in the Democratic administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. A white man, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by a black chief executive who recognized his invaluable contributions to the African American freedom struggle.

When Doar joined the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 1960, at 38, racial segregation remained in full force throughout the American South. The DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, to which Doar was assigned, was barely two years old. At the outset, no one — either inside or outside the federal government — had high expectations for the new division. The DOJ’s record on civil rights was dreadful, and there was little reason to believe that the division’s young lawyers would actively promote liberty and justice for black Americans.

Little reason, that is, prior to the Kennedy presidency and the emergence of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Burke Marshall, and their chief assistant, John Doar.

The transformation did not happen overnight, and there were times when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies wondered if the government’s chief law-enforcement agency would ever live up to its professed ideals and provide equal protection and due process to all Americans. Within this sometimes-adversarial relationship between activism and law enforcement, the federal official who inspired the most trust was Doar. More than any other government lawyer, he experienced the movement firsthand, learning his civil-rights lessons in the trenches of the Southern struggle.

Doar’s education began in earnest in May 1961 when he witnessed the Ku Klux Klan’s bloody assault on a busload of Freedom Riders at the Montgomery, Ala., Greyhound bus station. Looking out at the melee from the window of the adjacent federal courthouse, he grabbed a phone and provided his boss Bobby Kennedy with a chilling account of the carnage. Later in the year, he traveled throughout Mississippi in an effort to protect activists and black Mississippians exercising their right to become registered voters. After violence erupted in southwestern Mississippi in September 1961, Doar investigated the murder of local NAACP leader Herbert Lee.

In October 1962, Doar was back in Mississippi, this time as the protector of James Meredith, the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. After Doar escorted Meredith to the campus, white supremacists unleashed a protest that left two people dead, but with the help of an Army battalion, Meredith eventually completed his degree at Ole Miss. At the time of Meredith’s graduation, in June 1963, Doar was in Jackson, calming a crowd of black Mississippians attending the funeral of Medgar Evers, the Mississippi NAACP leader who had been gunned down in his driveway. Doar later presided over the prosecution of the Neshoba County white supremacists responsible for the brutal murders of three civil-rights volunteers: Andrew Goodman, Mickey Schwerner, and James Chaney.

When he wasn’t in Mississippi or Alabama, Doar was in Washington overseeing a widening range of civil-rights cases and helping to draft the bill that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He replaced Marshall as assistant attorney general for civil rights in December 1964, yet the promotion could not keep him behind a desk for long.

In March 1965, as white-supremacist opposition to the voting-rights struggle in Selma, Ala., threatened to explode and several thousand voting-rights activists marched from Selma to Montgomery, Doar symbolized the presence of federal protection by walking a half block ahead of the throng. Later, following the murder of Viola Liuzzo, a white woman from Detroit who had been transporting black volunteers along the Selma-to-Montgomery route, Doar personally supervised the prosecution of the Klansmen responsible. He left the Justice Department in 1967 to practice law in New York City, returning briefly to serve as head counsel of the House Judiciary Committee during the Watergate hearings.

Through it all, Doar was a consummate advocate of social justice — a firm believer in the role of law as a guarantor of freedom and democracy. He radiated greatness. Noting his tall and imposing physique, his quiet strength, and his air of integrity, the historian Taylor Branch once aptly called him the “Gary Cooper” of the civil-rights movement. Cooper, however, was an actor steeped in make-believe. Doar was the real thing.

When I interviewed Doar in 2005 for my book on the Freedom Rides, he was gracious and precise, connecting memory and history with disarming ease. The last time I saw him was a complete surprise. While waiting to join the 2014 P-rade, I saw a familiar figure approaching in a golf cart bearing the banner of the Class of 1944. I yelled out “John” and walked toward him, he nodded and smiled, and I shook his hand one last time as the cart rolled by. What a blessing to spend even a brief parting moment with one of the unsung heroes of our age.

Raymond Arsenault ’69 is the author of Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. His most recent book, co-edited with Orville Vernon Burton, is Dixie Redux: Essays in Honor of Sheldon Hackney, dedicated to the life and legacy of his mentor, a former Princeton history professor and provost.

In an interview from the Robert H. Jackson Center, Doar explains how the Nuremberg Trials shaped his arguments in the prosecution of the Neshoba County murders of three civil-rights workers.