Lives: Samuel W. Lewis *64

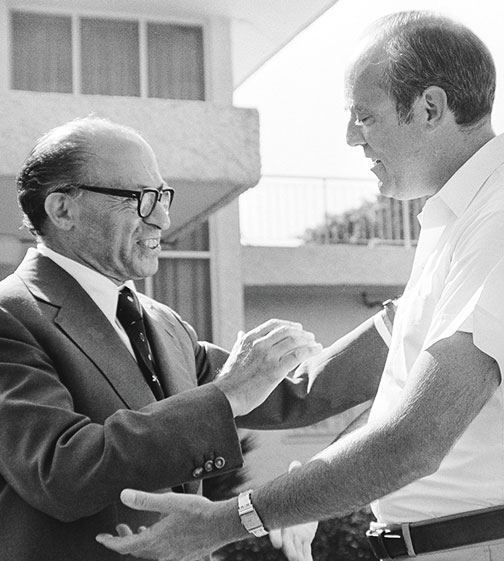

Samuel W. Lewis *64, right, with soon-to-be Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin.

Samuel W. Lewis *64, right, with soon-to-be Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin.

Samuel Lewis *64 was named U.S. ambassador to Israel in 1977, arriving at a propitious time. After three decades in power, Israel’s Labor Party had been defeated by Likud, the first time a right-wing political party controlled the government. The new prime minister was Menachem Begin, and political leaders in the United States knew little about him.

“For an ambassador, that’s an ideal situation, because you have a chance to define the person for Washington and to really have an impact on policy,” says Daniel C. Kurtzer, a professor of Middle East policy studies at Princeton, who worked for three years with Lewis in Tel Aviv.

Lewis, who hailed from Texas, would spend eight years in Israel, an unusually long tenure in such a politically sensitive post. Appointed by President Jimmy Carter, he served a key role in the 1978 Camp David talks between Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, helping to ease the tensions between the American president and the Israeli prime minister. In a 1998 oral history, Lewis recounted how a frustrated Carter told him that he thought Begin did not really want peace. Lewis responded that he thought the president was wrong and recommended a different approach: “honey before vinegar.”

After 13 days of negotiations, the two sides signed an agreement that led to a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. Lewis continued as ambassador under President Ronald Reagan, serving until 1985.

“Sam was able to be seen as both sympathetic to Israel, but also able to carry tough messages from the United States,” says Kurtzer, pointing to a peace plan put forward by Reagan in 1982, which was rejected by the Israeli leadership at the time.

Lewis began in the State Department in 1954, where he came under the influence of Chester Bowles, a dynamic politician and diplomat who served as undersecretary of state under President John F. Kennedy. Lewis took a sabbatical in 1965 to become a mid-career fellow at the Woodrow Wilson School. In the oral history, he said he attended Princeton to improve his understanding of economics and the role it played in development. It was “a terrific year” that accomplished what he had hoped.

Lewis, who was not Jewish, was widely admired in Israel and among diplomats in the United States. “He was someone who lived and breathed the U.S.-Israeli relationship and did more to effect it, shape it, and nurture it than anybody I know,” said Mideast peace negotiator Dennis Ross in a forum held in Lewis’ honor after his death.

Lewis continued to advocate for peace in the Middle East after he left Israel, arguing that the United States needed to play a key role in the process. “Peace between Arabs and Israelis will come only with the active and sometimes-intrusive support of U.S. diplomats, and especially of the U.S. president,” he wrote in an essay in Foreign Affairs in 2004. Yet he also thought American presidents should not be “over-involved,” as he believed Bill Clinton had been, and should let their deputies play a greater role. In 2013, Lewis expressed hope that Secretary of State John Kerry could play a leading role in negotiating with Israel.

After leaving Tel Aviv, Lewis served as director of the United States Institute of Peace, an organization chartered by Congress to work on conflict resolution around the world. In 1993-94 he was director of policy and planning in the Clinton State Department.

Writing in the Jewish Daily Forward after Lewis’ death in March, Aaron David Miller, vice president of the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., said, “America has lost a man of uncommon judgment and authenticity at a moment when we desperately need these qualities.”

Maurice Timothy Reidy ’97 is an executive editor at America magazine.

Lewis discusses the future of the Middle East in selections from speeches and interviews compiled by the Washington Institute for its Samuel Lewis Memorial Symposium.