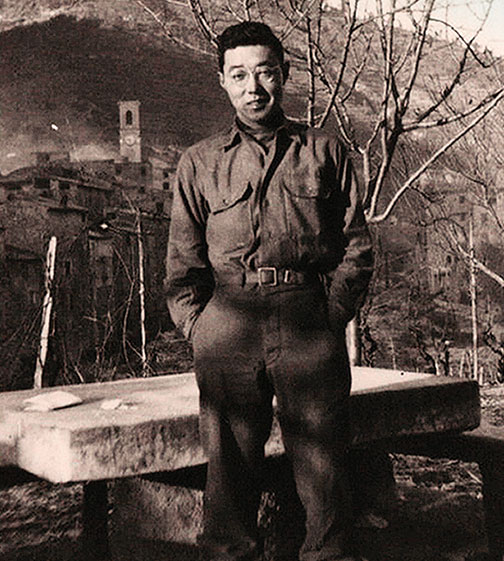

Lives: Yeiichi 'Kelly' Kuwayama '40

Lives-Kuwayama.jpg

Lives-Kuwayama.jpg

In April 1945, as a medic with the U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Yeiichi “Kelly” Kuwayama ’40 applied a tourniquet to the severed arm of 2nd Lt. Daniel K. Inouye. The future senator credited the medic with saving his life.

That moment may have earned him renown, but Kuwayama’s valor already had earned him recognition. He was awarded a Silver Star for gallantry during the 442nd’s harrowing rescue, in October 1944, of the “Lost Battalion,” which was surrounded by German forces in the Vosges Mountains of France. Kuwayama was wounded, but after two weeks in the hospital, he returned to the 442nd. It was in Italy’s Po Valley that he rescued Inouye.

The 442nd, made up entirely of Americans of Japanese ancestry, received more decorations for valor than any other unit in the war’s European theater; among them was the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor bestowed by Congress. Kuwayama himself received — in addition to the Silver Star — the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, Combat Medical Badge, Italian Croce di Valore, and French Legion of Honor.

Uncommon courage was not all Kuwayama displayed in his service. When German snipers targeted unarmed Nisei medics with Red Cross insignia conspicuously painted on their helmets, Kuwayama’s comrades decided to retaliate. Kuwayama told the men that shooting any unarmed medics with the Red Cross insignia violated the Geneva Convention. “Two wrongs don’t make a right,” he argued. They listened.

Such unrelenting principles marked Kuwayama’s entire 96-year life, often in the face of unrelenting challenges.

He was born in Manhattan to Japanese immigrants who ran both an art-goods store and a Japanese grocery store on East 59th Street. Upon graduation from Princeton, where he had majored in economics, he tried to get a job with the U.S. government, to no avail. He was drafted into the peacetime Army in January 1941.

His first assignment, to the 248th Coast Artillery, responsible for defense of New York Harbor, ended abruptly when a general visited and asked for his name. “I said, ‘Private Kuwayama, sir,’” he told an audience in 2005. “The next day, I was transferred out. It was the fastest thing the Army ever did to me.”

Kuwayama was shuffled to an ordnance battalion (“requisitioning auto parts”), then put in the laundry room of a station hospital, sorting linen. Soon he was moved to the operating room as a surgical technician, eventually becoming an instructor.

“I asked to be sent to training at Walter Reed Hospital,” he recalled in 2005. “Strangely, they didn’t send me. I also applied to the 90-day officer [candidate school], since I was a college graduate. They didn’t send me there, either.” Finally, when Kuwayama learned that the Army was forming an all-Japanese-American squad, he volunteered and was assigned to the 442nd’s Medical Unit. He had received his sergeant’s stripes before Pearl Harbor, he has explained, and “even though I spent a lot of time in combat, was wounded, and received the Silver Star, I never got promoted again.”

“Kelly was incredibly astute when it comes to what was within his control,” says David Wu ’79. “He could be extremely flexible, as long as you did not violate his moral principles. If you did, he could be very strong in response, very strict.”

Kuwayama once put it this way: “Being an American in outlook yet knowing myself to be a Japanese American made it hard at times, but they are complementary aspects to who I am. What I take from both is the American gung-ho spirit of aspiring to greatness tempered by the more down-to-earth Asian acceptance that there are processes beyond the reach of understanding. Unlike the West, the East doesn’t ask why something happens so much as what’s next. Looked at that way, I can say that both these approaches have led to a balanced life and an ability to stay true to my own self.”

Kuwayama used the G.I. Bill to attend Harvard Business School and earned an MBA in 1947. Still, no one would hire him — in Washington or on Wall Street. So he left the country, taking a job with the Japanese investment-banking firm Nomura Securities. After working in Japan, he returned home, becoming the company’s U.S. general manager. Later he worked for the U.S. government and for the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, now defunct, which was created to educate the public about the internment of Japanese Americans.

Kuwayama was one of the first Japanese Americans to attend Princeton. In the late 1970s, he helped found the Asian American Alumni Association. He also established a planned gift to create the Yeiichi Kuwayama Student Fund, in support of Asian and Asian American students at Princeton.

“His military role was remarkable,” says Wu, “but his role as a Princetonian even more so. ... He cared about the next generation. He was passionate about his service with the Asian alumni, so that what he experienced would not be repeated.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a San Francisco-based journalist and author of Sin and Syntax and Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch.

Kuwayama and fellow World War II veteran Grant Ichikawa read from the Constitution at a 2009 event sponsored by the People for the American Way Foundation in Washington, D.C.