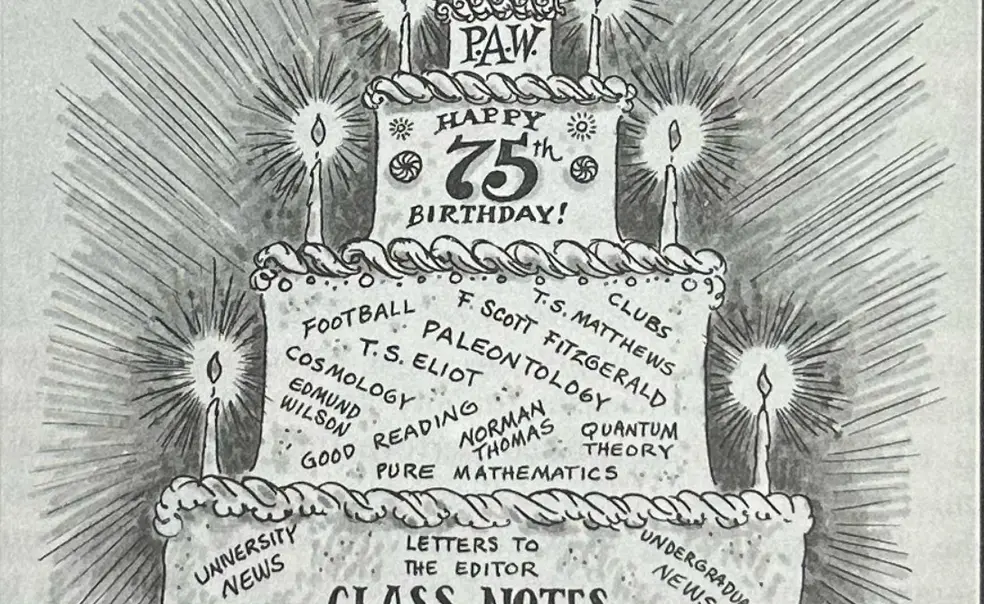

Although PAW is celebrating its 75th birthday this month, one can argue that the magazine is really 81, for it has continued without interruption the tradition begun by The Alumni Princetonian, which was founded in April 1894. In any event, PAW is one of the oldest weekly journals in the country, and the only alumni publication still coming out weekly. Through the years, its purpose has remained “to record news of the alumni and at the same time to review without partiality the achievements and problems of the administration, the faculty, and the student body of Princeton University.” A brief history, entitled “Confessions of an Alumni Magazine,” ran in these pages on September 25, 1973. It promised a sequel examining “what’s appeared between the covers of our 2,500 issues,” and this seems the appropriate occasion. Our writer is doubly qualified for the task, being both a historian and a former PAW editor (1955-69). The birthday cake above was contributed by Henry R. Martin ’48. — Ed.

To commemorate the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s 75th birthday — the date, April 7, slipped by during PAW’s spring hiatus — the editor asked me to write a brief retrospect of this journal. In preparation, I read through the entire 75 years of back issues in one week, a feat of time compression comparable to chewing a case of bubble gum in one morning: it’s not very tasteful, but after it’s all over you certainly know what bubble gum tastes like…

The taste of PAW, in general, has remained remarkably consistent over its three-quarters of a century. The magazine was set up to be independent of the university administration, and the first editor undauntedly fought Woodrow Wilson by loading his columns with pro-club material during that president’s battle against Prospect Street. Soon PAW had a Board of Editorial Direction, largely composed of journalists who have taken care that the magazine was professionally run on a non-house-organ approach, telling indignant readers and deans to keep their cotton-pickin’ hands off the valorous editor.

Indignation there has been aplenty. Two generations ago PAW published a series of guest columns entitled “If I Were Running Princeton,” which clearly implied that no one was running it. Back in the 1920s a really eccentric editor used to work off his sadistic impulses by printing savage reviews of faculty books; this raised such a row around the faculty club that the gentle John Grier Hibben finally said, “Either he goes or I go.” But for the most part Nassau Hall has stoically endured the magazine’s occasional lapses of taste, in the spirit of President Neilson of Smith, “It is better that the alumni should be alive, even if they are kicking.”

The changes in PAW’s editorial content over the years have reflected the evolving tastes of it audience. In the issue of September 25, 1907, for instance, the editor wrote, with unconscious irony, that alumni talk was all about Wilson’s proposed reform of the clubs “even to the exclusion of football prospects.” Football continued big through the 1920s, when two separate accounts of the Yale game would total perhaps 10,000 words in 8-point type. As late as 1948 PAW reported signs in Palmer Stadium — “We Want Crisler” — in memory of the glory days of the mid-’30s, with bloodied warriors shaking their fists at weeping stands, snake dances, raccoon coats, special trains, and victory bonfires. Now all that is gone; PAW long ago gave up its play-by-play account in favor of a game chart, which eventually disappeared without apparent complaint. Last fall’s angry letters over the Rutgers-game goalpost incident do not begin to compare with the screams of rage that filled page after page following the disastrous (1-7) campaign of 1931, which literally drove the coach crazy.

Like football, the club system has occupied a steadily declining proportion of PAW’s space in recent years. The vigorous defense of Prospect Street undertaken by the magazine in the early 1900s persisted into the late ’30s, when the administration attempted another unsuccessful reform. In the ’50s the clubs in self-defense instituted a system of “100 percent” membership, but the vastly increased number of public-school graduates attending the university presented an unprecedented quantity of “problem” candidates. Letters appeared in PAW quite seriously advocating that alumni screening committees be formed around the great metropolitan high schools of the Northeast to cut off the volume of, to use Dr. Johnson’s elegant phrase, “unclubbables.” Today those once-heated issues are extinct volcanoes: Prospect Street cannot attract even 50 percent of Princeton’s new free spirits, and half of the clubs have quietly folded.

Nonetheless, a longing for the old Princeton stereotypes can still be found in PAW’s letters column. Let this one letter stand for 75 years of them: “What is the matter at Princeton?...Are we to contribute in our very humble way to the perpetuation of an old and deeply reverenced ideal merely helping to build up a nursery for dilettante intellectuals too concerned with theorizing about life to come right down and live it? Too sophisticated to feel heart and soul enthusiasm for any and every undertaking in which a fine and spirited performance will bring their university honor?” (The author was a class secretary of the ’90s threatening to withdraw his Annual Giving and berating the undergraduates of the early ’30s for failing to produce for him a winning football season; as Harold Dodds observed, flogging the younger generation has always been good therapy for the old.)

In keeping with the ascension of Princeton from what was in 1900 essentially a glorified version of an Exeter-Andover type boarding school to a true university, there has been a progressive upgrading of PAW’s intellectual content. From the beginning, the writing has generally been professional and tight, with the bare minimum of presidential chapel addresses and institutional prose (the magazine’s first editor was a Pulitzer Prize winner). PAW has carried articles by T.W. Eliot, T.S. Matthews (1922), Edmund Wilson (1916), Norman Thomas (1905), and a charming “How to Succeed in the Advertising Business” by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1917); Arthur Krock (1908) used to quote the magazine regularly in his New York Times column (so embarrassed at his source that he would downcase the title). A 1958 editorial on “The Natural Superiority of High School Graduates” was quoted all over the country. Since World War II particularly, PAW has tried to popularize scholarship in the Scientific American mode, with pieces on paleontology, quantum theory, cosmology, comparative literature, pure mathematics, and so on.

Despite shifts in emphasis over time, PAW’s basic formula has remained unchanged: a quick sandwich of letters, university news, undergraduate views, scholarship, and sports, the core of which — and the center of reader interest — is the Class Notes. No other alumni magazine can match PAW’s volume of alumni news or the dedicated corps of class secretaries who report it. What emerges from this incredible mass of trivia is a collective portrait of the Princeton graduate: when the PAW reader looks into the Class Notes, he sees a mirror of himself, and evidently he likes what he sees.

What has enabled PAW to survive as the only alumni magazine in the country still publishing weekly (although financial pressures have gradually reduced the number of issues from 36 to 27 a year) is the remarkable cohesiveness of Princeton’s alumni body, reinforced by reunions, class parties, regional associations, football weekends, and programs like Princeton Today and the Alumni Colleges. Between these events, PAW subscribers keep their memories of bright college years green by reading about their bright, cheerful, successful classmates. While each class at graduation votes a member “most likely to succeed,” he turns out to be just about everybody. In some of the older classes the representation in Who’s Who reaches 25 percent. (The publisher of Who’s Who once advised the parents of young America on how to get a son into his pages: “Send him to college. Princeton, if he can make it.”) By a sort of type-casting, Princeton has historically drawn from what C. Wright Mills called “the power elite” — or those industriously trying to get into it.

One of PAW’s first issues carried the couplet: “Her educated graduates are Princeton’s special pride/To turn out mere businessmen Old Nassau has never tried.” But how is one to balance this admirable aim against the complaint of a dean, quoted a generation later, about “the predominance of the uneducated among our graduates.” To be sure, anti-intellectualism, or rather indifference to intellectual endeavor, is not peculiar to Princeton. Stuart Chase wrote a book about his class at Harvard in later life, and found “a handful of choice minds followed by battalions in white knickers pursuing golf balls.”

It was not surprising, then, when a judge for the annual alumni magazine contest remarked some years ago about the irony that these journals, which collectively have the most educated readership in the nation, “read as if they were written for an immature, unsophisticated audience.” Although PAW is perennially ranked among the best of the alumni publications, it has not participated significantly in the intellectual life of the university. Instead, it often seems to harken back to Booth Tarkington (1893), that avatar of college spirit, who wrote: “Princeton kept us boys. And when we grow completely up, God save us.”

Today the university has passed the sound barrier of 3,000 undergraduates, in which everybody knew virtually everybody else, to 4,200, plus a graduate school of 1,000. The comfortable homogeneity of the past has disappeared into a world of variety and every sort of excellence. A half-century ago, Fitzgerald could write that Princeton was surrounded by “a ring of silence,” but that ring has been burst, and Old Nassau is now very much a part of the real world, a true university. The challenge facing PAW in the remaining quarter of the century is to find its place in this vastly enlarged scene.

This was originally published in the April 15, 1975 issue of PAW.

No responses yet