Aaron Burr 1772’s Forgotten Family

Tracing the mysterious life of Mary Eugenie Emmons from India to Haiti to Philadelphia

ONE NIGHT IN KOLKATA, INDIA, last summer, I received an article via WhatsApp written in Bengali more than 100 years ago. It had been found in a public library in Chandannagar, a former French colony about 20 miles north of the city. The first page showed an image of a bill of sale for an 8-year-old boy named Chama Bagdy. The boy’s father, Atmaram Bagdy, had sold his son to a Frenchman for “7 Madras Rupees” on May 25, 1735. The agreement stated that the boy would be baptized and become Catholic at the cost to the owner.

Subham De, a local historian, had sent the article, which was published in a magazine in 1921 by Charuchandra Roy, a schoolteacher and mayor of Chandannagar during the French occupation.

Why would a parent sell his child? Was Atmaram unable to feed his son? And did the father ever see the boy again?

The bill of sale had signatures of five Frenchmen and an “X” made by Atmaram to indicate that he did not know how to read and write. The article noted two other bills of sale in the same year. In October, Chama was sold for 25 rupees to “Mr. Therese,” and a month later, Chama was sold for 50 rupees to “Mr. Theroux.” And that is where the trail for Chama ended. Perhaps he had been baptized and had his name changed, as the French slave codes required. Perhaps he had been sent to Reunion or Mauritius in Africa to work in the sugarcane fields, or to Haiti.

Little is known about the trafficking of slaves from South Asia. Most of the scholarship on modern slavery focuses on the trafficking from Africa to the Americas from the 1600s to the 1800s. Yet historian Richard Allen estimates more than 100,000 slaves came from India during the same period, trafficked by Portuguese, Dutch, French, and English colonizers. These men, women, and children left few imprints in the written records. One such person was Mary Eugenie Emmons, who appeared in 1780s Philadelphia and had a family with Aaron Burr Jr. 1772, the third vice president of the United States of America.

IN 2019, I CAME TO PRINCETON TO TEACH in the University’s journalism program after several years of working in India as a journalist. At that time, I read an article published as part of the Princeton & Slavery Project at the University by Sherri Burr *88, titled “Aaron Burr Jr. and John Pierre Burr: A Founding Father and his Abolitionist Son.”

Burr “fathered two children by a woman of color from Calcutta, India,” the article read. “Their son, John Pierre Burr, would become an activist, abolitionist, and conductor on the Underground Railroad.”

Like most people, I knew Aaron Burr primarily as the man who shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. I also knew that Burr and his father were Princeton legends. Aaron Burr Sr. was Princeton’s founding trustee and its second president. On campus, Aaron Burr Hall, named after Burr Sr., stands on the corner of Washington and Nassau streets. Aaron Burr Jr., the son, graduated from Princeton at age 16 and went on to be vice president of the United States during Thomas Jefferson’s first term. Along with James Madison 1771, he is one of the key figures connecting the University to the founding of the American republic. Both father and son are buried in the cemetery in downtown Princeton, two blocks from Nassau Hall.

Until then, I had never heard of Burr’s two children from an out-of-wedlock relationship with a woman from Calcutta. I grew up in Kolkata, as it is now known, until age 12, when my family moved to New Jersey. After graduating from Princeton in 2000, I returned to work as a newspaper reporter and later wrote a book, The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta, about my experiences.

After reading her piece, I called Sherri Burr, a retired law professor in New Mexico. She told me she had not known of her family connection to Aaron Burr until 2016, while doing research for Complicated Lives, her book about a different part of her family history in the American South. At that time, she had taken a DNA test. “It said I was 2% South Asian and 1% English and I thought that was strange,” she says. “I had grown up being told there was a big family secret, but I had no idea. I started looking and doing some research and I found that Aaron Burr had had this relationship with this South Asian woman.”

Mary Eugenie Emmons lived in Philadelphia and had two children, Louisa Charlotte Burr, born in 1788, and John (Jean) Pierre Burr, born in 1792. Both Burrs became prominent members of the so-called “Colored” community in 19th century Philadelphia and married free African Americans. Their descendants were part of the Black elite in Philadelphia and well known in the community as important figures in Black churches and the abolitionist movement.

Allen Ballard, 93, a retired history professor at SUNY Albany, who grew up in Philadelphia, had always known he was a Burr. But in his childhood, Burr’s reputation made him hesitant to trumpet his lineage. Burr had been accused of attempting to overthrow the U.S. government in an armed rebellion in the American Southwest and was tried in federal court for treason. Even though he was acquitted, his reputation as a potential traitor remained.

“I’m a Burr and I accept that,” Ballard tells PAW. “Growing up there was a feeling we didn’t need to talk about it too much because of the trial and the treason thing. It wasn’t something to go bragging about in Philly. There was a shame about it.”

In his 1984 book, One More Day’s Journey: The Story of a Family and a People, Ballard provided a detailed genealogy on his mother’s side of free Black men and women in Philadelphia all the way back to John Pierre Burr.

The son of Aaron Burr was a barber who cut white men’s hair and used his shop as a station on the Underground Railroad to give safe passage to slaves fleeing the South. Of John Pierre’s mother, Emmons, Ballard wrote that the family oral history said she was a servant in Burr’s household, that she had come from Haiti, and that she was an Indian woman originally from Kolkata. Ballard is the fourth great-grandson of Emmons. Several members of his family had collected scrapbooks, a common form of memorialization in Black families in America, about their connections to Burr.

One of the Burr descendants who had accumulated such scrapbooks was Louella Allen, a retired nurse from Philadelphia. In 2005, Allen attended the Aaron Burr Association meeting in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, with five members of her family and scrapbooks of information connecting them to Burr. The Aaron Burr Association is a group of 50 dues-paying members, comprising Burr descendants and history buffs who meet annually in different cities across the U.S. Its president since 1995 has been Stuart Johnson, a lawyer based in Maryland who is descended from a cousin of Burr.

Johnson says members of the association were split on whether to recognize Burr’s non-white descendants.

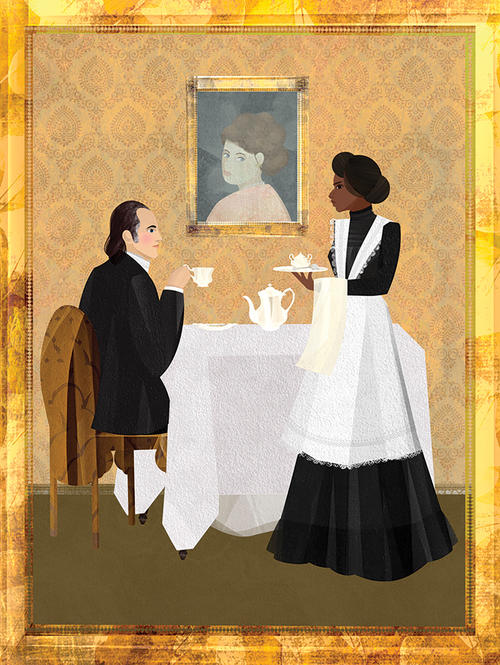

“It was kind of controversial,” Johnson says, “For one thing, Burr was cheating on his wife. His wife, Theodosia Prevost, was dying of cancer and he was having an affair with a servant in the household.”

Burr had two children by his marriage with Theodosia. Only one, a daughter also named Theodosia, survived to adulthood. Her only son died when he was a boy. As a result, Burr had no direct descendants through his children by marriage. The white relatives of Burr, like Johnson, who are members of the association, are all descended from Burr’s cousins. As Johnson explained, the only known direct descendants of Burr are Black, from the two children with Emmons.

Louella Allen died soon after the 2005 meeting. The question of Burr’s Black descendants lay dormant for more than a decade until September 2018, when Sherri Burr attended the association’s meeting in Morristown, New Jersey. She collected DNA samples from Burr’s white relatives, including Johnson. An autosomal DNA study — usually used to trace distant relatives — of the Black and white family members showed they shared common English ancestors. As a result, the Aaron Burr Association unanimously voted to recognize John Pierre and Louisa Charlotte as the children of Aaron Burr.

A few months later, in August 2019, the association erected a tombstone upon the unmarked grave outside Philadelphia where John Pierre was buried. It read: “Champion of Freedom and Justice, Conductor on the Underground Railroad, Son of Vice-President Aaron Burr and Mary Eugenie Emmons … .”

John Pierre’s father was one of the most written about men in American history. But Emmons appears in no census record, no birth, marriage, or death certificates, nor tombstone.

“We know Mary Eugenie exists because John Pierre exists,” says Sherri Burr, but there is no mention of her by name in any record. “She’s a secret.”

I WENT TO KOLKATA TO TRY TO FIND HOW Emmons’ story had started. It was August, monsoon season, muggy and wet. The colonial-era buildings with broad verandas and crumbling alabaster columns and the post-colonial concrete apartment blocks all seemed tinged sepia, as if the city was set in a flashback from a film. Until the mid-20th century, when the British left India, Kolkata was the largest city in Asia, the fourth largest in the world. From the 18th century to the 20th century, Kolkata was the capital of British India, a metropolis of tremendous wealth and misery, of lavish mansions and slums. From here, cotton, jute, silk, opium, and people were shipped across the world.

In the mid 1700s when Emmons was born, the era of colonial expansion in India had just begun. The European trading posts were villages along the Ganges River. For the next few decades, a global conflict would be waged between the British and French colonial forces for control of India’s resources. That war would stretch from India to Africa to the Caribbean to the U.S.

For clues about Emmons, I had contacted Sue Peabody, a professor of French colonial history at Washington State University who published Madeleine’s Children in 2017, an account of a Bengali woman named Madeleine, who was born around 1759 and traveled from Chandannagar, a French colony along the Ganges, about 20 miles north of Kolkata, to France in 1771, around the same time as Emmons was believed to have migrated. Madeleine was a domestic slave to a Frenchwoman, who moved to France and then to a French colony in Reunion, off the coast of east Africa. Madeleine’s story became known only because her son, Furcy, sued for his freedom in the Royal Court in Paris, and won.

The passengers of ships across the French colonies are listed in logbooks, many of which are now digitized, as are French colonial census records. But the names of passengers who are servants, slaves, or stowaways are rarely provided. The documentation on Madeleine in ship records and census records was sparse. And the documents regarding her status as a slave that were subsequently produced in court by her owners may have been falsified years later.

As Peabody wrote: “This project has taught me more deeply than I ever realized before how vast is the slippage between written evidence and historical truth. So many things have happened that were never recorded on paper. So many written records bend the truth for posterity.”

From Kolkata, I went to Chandannagar and the Dupleix House, home to the Indo-French Cultural Centre and Museum. The building had been the residence of French Governor Joseph Francois Dupleix and then home to a line of French administrators of the colony until Indian independence. The history of Chandannagar, as preserved in this museum, was the history of European trade, French rule, and subsequent Indian nationalist resistance. But how would a girl in the late 1700s travel from here to America?

One of the museum officials recommended talking to Kalyan Chakraborty, a local historian who had his own museum. I met Chakraborty at his large two-story family home, which doubled as a museum of Chandannagar heritage.

Chakraborty, 80, is a former mountaineer who scaled the Himalayas. His museum highlighted several local luminaries, such as Radhanath Sikdar, the first person to correctly calculate the height of Mount Everest. Chakraborty made Darjeeling tea and we drank out of matching ornate mugs while he wondered about what may have happened to Emmons.

“There was a slave trade here,” he said. “The Portuguese were notorious for it, as were the Dutch and the British.”

There were slaves being trafficked in Southeast Asia to work in French colonies in rice cultivation. People were abducted from the nearby villages and sold to the Portuguese and then to the English, who would ship them around the world, he said.

"The French stopped the slave trade. They passed a law that there could be no slave trade in their colonies,” he said. “We have no record of the slave trade here. We have only the record of its end, when the law was passed.”

Chakraborty began to make some phone calls. He said he had a network of young amateur historians; among them was Subham De. “He can look at a chair and say, ‘That used to belong in the chapel’ just by looking at the markings. He has that kind of eye,” Chakraborty said.

De arrived by motorbike dressed in a kurta pajama. He was a college graduate in science with a passion for history.

“1760,” he said, considering Mary Eugenie’s purported year of birth. “So in 1770, she would have been 10 years old, in the year of the famine.”

The famine of 1770 is an infamous calamity in Bengali history. In 1757, the British East India Company had conquered Bengal and imposed a tax system that forced peasants to pay their share of rents even if crops had failed, as they did in 1770 during a drought. This led to a widespread famine across Bengal in which 10 million of the 30 million locals are reported to have died. Many also fled or sold their children so that they might survive.

“There are three possibilities,” De said. “One, she married someone here and went with him. But if she was born in 1760, she would be 10 in 1770. She could have been married, but it’s unlikely. Two, she was sold as a slave, in which case, there would be a bill of sale, and the name of the buyer would be named; and she would have been baptized as a Catholic, and that record would be in the church. We have records of such sales and baptisms. Three, she was taken by someone or was a stowaway with no documentation.”

The name Mary Eugenie Emmons, as a wife or relative, appears on no ship record or census record of the time. But not all names are recorded.

That night De sent the article in Bengali, written nearly 100 years ago, which he had discovered at the public library and showed the bill of sale from 1735 of a slave, Chama Bagdy. I read the article and wondered if Emmons had a name and background like Bagdy’s.

The same year that Atmaram Bagdy sold his son, 12,000 people were taken prisoner in a war between two Indian kings in Patna, a town farther upriver along the Ganges. The governor general in Chandannagar, Dupleix, asked his agent in Patna to buy 300 people who had become prisoners of war.

“These 300 slaves will be very suitable for [Mauritius]; it looks like they will be cheap,” he wrote.

In the early 1700s, the French had seized control of two islands off the east coast of Africa that are now known as Mauritius and Reunion and turned them into sugarcane plantations. They needed slaves to cut down forests and cultivate sugarcane.

There are records of extensive communication between the French colonies in India to coordinate the purchase and transport of slaves to the plantations in Mauritius and Reunion. Wars and famines were particularly lucrative for the slave traffickers because the number of people sold in the slave markets grew, and as Dupleix noted, slaves became very cheap. But we have no idea what happened to Chama Bagdy after his sale, or whether he ended up on the other side of the world like Mary Eugenie Emmons.

The French had colonies from Chandannagar to New Orleans. The jewel in France’s empire was Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean Sea, today known as Haiti, then the most profitable colony in the world. The island produced 40% of all the sugar consumed in Europe. Sugarcane was grown on large plantations mostly owned by a few thousand white landlords and worked by several hundred thousand Black slaves. According to Ballard’s account and those of others in the family, Emmons was believed to have been in Haiti in the 1770s before going to Philadelphia, and again in 1791, when slaves began a revolution to overthrow the French plantation owners and establish a new state. Her son John Pierre was born on a ship returning from Haiti to Philadelphia in 1792.

Most of the slaves who were brought to work in the sugar plantations in Haiti came from Africa, but there were also Indian slaves. Haitian newspapers mention Indian slaves and free people, and there is a record of at least one ship, Le Cibele, that brought 386 Indian slaves to Saint-Domingue in May 1778.

Across the French colonies, people who were enslaved were designated on census records and ship records as “Negre” or “Noir” for “Black,” irrespective of whether they came from Africa, India, or elsewhere in the colonies. In the French system of chattel slavery at that time, “Black” designated the kind of person who could be enslaved and transported like raw materials according to the needs of the empire. By French law, each sale of a slave had to be recorded by the state to be taxed, and each slave had to be baptized, his or her name changed to a Christian one. But these rules were not always followed; the illegal sale and transport of slaves was common.

In Chandannagar, census reports from the 1760s show that the average age of sale was 7, because younger slaves were easier to train than adults. Perhaps Emmons had been sold for a few rupees as a girl during the famine of 1770. But no scraps of paper, like Chama’s bill of sale, could be found to illuminate her past.

It was as if Chama and Emmons were on two sides of a mirror. Chama appeared in the historical record at age 8 as an object of sale, and then disappeared forever. Emmons emerged on the other side of the world, on the center stage of American history.

I NOW LIVE IN PRINCETON, on Witherspoon Street, a few blocks past the cemetery where Burr and his father are buried. During the 1800s, this street — which begins at Princeton University’s entrance at FitzRandolph Gate — was called Guinea Lane or African Lane because of the ancestry of the people who lived here. They were the descendants of Africans, enslaved and brought to North Carolina, who fled or became free. Some labored in the dining halls and dormitories of the University. One in five people in Princeton was Black, and they mostly lived in this neighborhood, stretching from Nassau Street all the way down Jackson, John, and Witherspoon streets, to where I now live. Many of the elderly homeowners in our neighborhood are part of that historic Black community.

Until the 1940s, Princeton was segregated. Restaurants, hotels, bars, and even the public high school were for whites only. There was a separate elementary school for Black children. One afternoon, I was walking past the former Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children, where a young Paul Robeson went to school, when I ran into one of my daughter’s friends, a 7-year-old girl with a Black father and a white mother. She was standing outside the gate of the former Colored Cemetery on Witherspoon Street with her family, reading the placard and trying to imagine a past when even the dead were separated by race.

Then she turned to me and asked: “If you were living here in the time of slavery, then would you have been a slave?”

I had never asked myself that question. What would I have been if I had been here, like Emmons, more than 200 years ago? I certainly would not have been designated “white,” so I suppose I would have been “Colored,” I said.

Princeton today is a town of 30,000 residents. Its population is about the same as that of Philadelphia in the 1770s. In such a small place, Burr’s “Colored” family and its Indian roots likely would have been known to many people. President Thomas Jefferson, Burr’s rival, had six children with Sally Hemings, a slave on his plantation. Their relationship was widely known even though there is little written record of Hemings.

There was a second person in Burr’s household who came from Kolkata. Azar Le Guen was at least a decade younger than Emmons and began working as Aaron Burr’s servant around 1799.

Le Guen had come from Kolkata with François Joseph Paul de Grasse, an admiral in the French navy who spent several years in Kolkata before arriving in America. He fought against the British in the American Revolution and was friends with Burr. Perhaps after his death, the boy became a part of Burr’s household. After the “gradual abolition” of slavery was introduced in Pennsylvania in 1780, many former slaves became servants in the households where they had been enslaved. It’s unclear if de Grasse was the owner and/or the father of Le Guen. What is known is that Burr gave Le Guen property in New York City, and Le Guen went on to become a prominent member of the free Black community in New York. He changed his name to George DeGrasse and was among the first people of Indian descent to become an American citizen.

There were other Indians like Emmons and Le Guen who lived in the “Colored” communities in New York and Philadelphia. Many of these people, like John Pierre and Louisa Burr, married partners of African heritage and merged into the community of free Black people.

Emmons’ daughter Louisa and her husband were active in the support for the revolution in Haiti and lived there for two years to help build the first free Black state in the Americas. One of her sons, Frank Webb, authored the second novel ever written by a Black person in America, titled The Garies and their Friends, which contains the fictionalized love story of Burr and Emmons.

There are no known written records of Burr and Emmons’ relationship or of any part of Emmons’ personal life, no way to know her thoughts and feelings towards Burr or her new homeland. The last mention of her is on a church receipt from 1826 at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the first Black Episcopal church in the U.S., which was founded in Philadelphia. At the time, families would reserve pews in church with annual donations. John Pierre’s pew receipts from 1818, 1822, and 1826 reveal cash payments of $5 a year to reserve a pew for “self, wife and mother.”

No one knows when Emmons died or where she is buried. The gravestone erected in 2019 to honor John Pierre sits above the remains of several other members of his family whose graves are unmarked. Stuart Johnson and Sherri Burr both speculate that among them are Burr’s wife, some of their 10 children, and Emmons. Burr, the retired law professor, says the DNA from those bones could prove Mary Eugenie Emmons’ identity “beyond a reasonable doubt” and complete her story.

But there are no plans to dig up the dead. Sherri Burr recognizes that some truths have been lost to history. She says, “You’d need a court order, and some would view that as sacrilegious. Plus, it’s expensive! I’m definitely not going to go there.”

Kushanava Choudhury ’00 is a writer based in Princeton. He is working on a book on slaves, runaways, and fugitives who shaped the New World. He can be reached at kushanava@gmail.com.

5 Responses

Terry L. Burr

2 Weeks AgoHistory Lesson

I have received in-depth clarity on my family history. Thanks.

Penelope Rowlands

1 Year AgoAn Intriguing Piece of Scholarship

A fascinating piece! As someone with an academic/journalistic interest in Aaron Burr Jr., I’ve long wondered how a servant of Indian origin ended up in his household. In this intriguing piece of scholarship, Kushanava Choudhury gives a plausible, if horrific sense of the twists and turns that could have brought Emmons from Kolkata to the New World.

Suzanne Geissler Bowles, historian, Aaron Burr Association

1 Year AgoFantastic Research and Detective Work

This was a fantastic piece of research and detective work. I look forward to meeting the author in September at the Aaron Burr Association meeting.

Editor’s note: The writer is a professor of history, emerita, at William Paterson University and a contributor to the Princeton & Slavery Project.

Stuart Fisk Johnson, president of the Aaron Burr Association

1 Year AgoImportant Research Findings Concerning Aaron Burr Jr. and Others

Congratulations to Professor Kushanava Choudhury for his new research on this subject, which is important to our members of the Aaron Burr Association. We are pleased that Professor Choudhury will be the featured guest speaker at our annual meeting and luncheon on Sept. 7. I invite responses from readers.

Frederick Beavers ’87

1 Year AgoWell-Researched Article

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this well-researched article. It reminds me why Princeton’s students and alumni are special. Keep up the excellent work.