Alumni Day: Pathways to Better Lives

Honorees Noor ’73 and Eakes *80 address national and global concerns

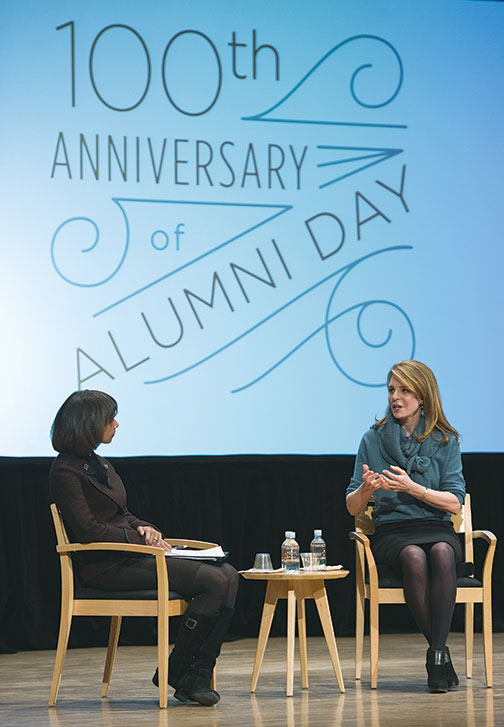

Social justice and gender equality were central themes of many Alumni Day speeches and forums, as alumni and students called for empowering women, addressing racial injustice, and using homeownership to break the cycle of poverty. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Alumni Day, the event was held over two days, Feb. 20 and 21, and though a storm brought several inches of snow, more than 1,000 Princetonians made it back to campus.

In her speech Saturday morning, Queen Noor of Jordan (formerly Lisa Halaby ’73), winner of the Woodrow Wilson Award, said that women should play a more prominent role as policymakers in the Middle East: “Women are not just a special category of problems to be addressed or ignored. They are the key to the solution. ... Opposed to violence, whether by tradition, temperament, or training, they have long relied on creative strategies to stop war and nurture peace.” The Woodrow Wilson Award is Princeton’s highest award for an undergraduate alum.

Though many people believe the oppression of women in parts of the Muslim world is a result of Islam, Noor explained that some practices seen as coercive by Western nations stem from ingrained social traditions and are not mandated in the Quran. Seventh-century Islam granted women political, legal, and social rights that were unheard of at the time, she said.

Noor also reflected on her time at Princeton, where she was a member of the first undergraduate class that included women for all four years. She developed “the diplomacy and survival skills required in a class of 92 women on a campus of 3,200,” which prepared her for challenges she faced as queen, she said. Activism on and off campus, including her experience in civil-rights marches, exposed her to a variety of people and ideas, some of which inspired her to work in the Middle East, she said.

“Every aspect of Princeton life can provide pathways to the truth,” she said. “Those pathways lead out through FitzRandolph Gate, thrown open to the world by the Class of 1970 and never again closed.”

Noor’s talk followed an address by Martin Eakes *80, CEO of Self-Help and the Center for Responsible Lending, who described his work offering fair loans to poor borrowers. He received the James Madison Medal, Princeton’s highest honor for a graduate alum.

Eakes launched Self-Help in 1980 with $77 earned from a bake sale. Today, the nonprofit community-development lender and credit union has $2 billion in assets and 43 branches in several states. It has made loans of $7 billion to people, businesses, and nonprofits deemed too risky by banks.

“I made a bet on African American single mothers,” said Eakes, who was raised in a rural North Carolina community whose population was nearly all black. “If they had a chance to own a home, they would pay back any loan that was given to them on fair terms. I had faith that poor people were better borrowers than rich people, and over 30 years, they have proven me right.”

He added, “Homeownership is the single best tool for breaking the cycle of poverty. Not because it’s an asset, but because it changes the psychology of a family. It stabilizes the family, it changes what they think is possible, and it changes the neighborhoods they live in.”

Among other activities, a Friday forum on women and the eating clubs drew more than 250 alumni and students (see page 10). A panel discussion about recent activism on campus was prompted by student protests about the decisions not to issue indictments in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, unarmed black men who were killed by police. Hundreds of Princeton students participated in the demonstrations.

Students on the panel discussed how some professors have made racially insensitive comments in class. The students said they would like University employees to undergo mandatory training on interacting with people of different cultures.

Naimah Hakim ’16, one of several students on the panel, said, “I did not fully understand the many ways that racism can manifest both covertly and overtly until I came to Princeton.” At the start of her college career, she said, “I identified as a student first, but over my few years here, I identify as a black student.”

Several former student activists in the audience, including Sally Frank ’80, whose lawsuit forced the all-male eating clubs to accept women as members, offered support. Frank told the panel she had donated her notes from her time protesting apartheid in South Africa to Mudd Library and encouraged students to use them to find names of alumni who may be interested in helping them.

“I hope there are ways that those of us who can’t just hop over here — I live in Iowa — can provide support to you in other ways than our physical presence,” Frank said.

Alumni Day — always more sedate than Reunions — had many celebratory moments as well. It opened Friday afternoon with special anniversary offerings: a reception and an event at which a dozen professors and students gave rapid-fire lectures and performances — including slam poetry and Taiko drumming — related to language. There were the Alumni Day staples: the moving Service of Remembrance, the luncheon at Jadwin Gymnasium and recognition of award winners, a talk by Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye on college admission, and a chemistry demonstration based on the experiments of Professor Hubert Alyea ’24 *28, aka “Dr. Boom” (see page 64).

“Alumni Day has historically been a time for Princetonians to come back to campus when it is in session, participating in lively conversations on a variety of topics,” said Associate Vice President of Alumni Affairs Margaret Miller ’80. “We thought that alumni would be interested in these topics, which are being discussed by students today, and they were.”

No responses yet