From the Archives

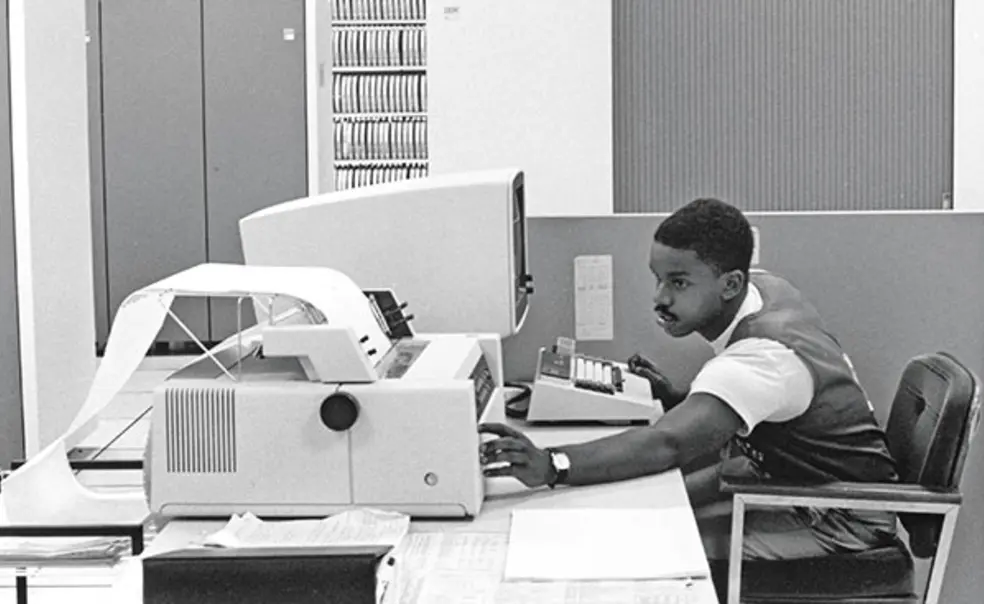

Before the days of home or personal computers, Princeton students had to trek to the Computer Center to create their work and print it on dot-matrix printers with perforated continuous-feed paper, as the student in this undated photo is doing. Do you have an interesting story about early computing at Princeton? Let us know in the comments below.

7 Responses

Rick Ross ’85

7 Years AgoStumped by a Seventh-Grader

In response to your request for an interesting story on early computing, I have an anecdote.

I was a consultant at the Computer Center from 1981 to 1985. Around 1982, a seventh-grade class from a local school came for a tour, and I was asked to lead it. I took them into the basement to see the “computer,” an IBM mainframe, but knew they would be bored to see little more than red- and white-paneled boxes. The tape drives, spinning forward and backward, intrigued them a little. Then I shared with them the statistic that a computer could do an operation in the time it takes light to travel one foot – having some idea of the speed of light, this blew my mind, but again, I realized that they would be nonplussed.

Finally, I thought I could show them a simple multiplication. We went back upstairs and sat around a terminal, and I loaded an early program called APL (which stood for “A Programming Language”). I asked them for a large number. They all volunteered their biggest numbers, and I typed one in. Then I typed the multiplication sign. Then I asked them for another big number, and I typed that in. Realizing that the program would return the product in scientific notation, I paused to explain that the computer would give the answer in a strange format with an E in it, but that it would be correct. I then hit the enter key, and the answer immediately appeared on the screen. “Wows” went all around, except one. He exclaimed, “Uh, uh. You cheated. The computer had time to think about it while it was on the screen!” At a loss for how to explain myself out of that, I accepted defeat.

Richard Sobel ’71

7 Years Ago‘A Long-Standing Reminder of Murphy’s Law’

The photo and request for recollections of early Princeton computing brought several RAMs from this former late-night denizen of the Computer Center down Prospect Avenue.

First, introduced to the computer for a statistics course senior year with Albert Beaton, it was amazing to punch an equation onto computer cards and see the answer jump out shortly afterward on green-lined sheets of computer paper. No calculator or hand-figuring needed!

Second, as a grad student doing a thesis in social sciences at UMass while coaching part time on the inaugural Princeton women’s track team, I was eligible for a computer account, based on my old U-Store number. I frequented the below-ground keypunch and ready-rooms late into the night (when computer time was cheaper) with a number of obscure and future notables.

One was John Nash *50, later Nobel Prize winner for game theory, who hung around nights at the Computer Center, perhaps partly from isolation before becoming famous. Another was a group of Italian musicologists who were apparently pioneers in computer music, which they occasionally played for listening pleasure. And still another was Kibbie (Qubilah) Shabbazz ’83, daughter of Malcolm X and Betty Shabbazz, whom my former professor Jan Carew, a friend of Malcolm’s, had also mentored (Carew later wrote a book about conversations with Malcolm).

Third, after asking so many questions (what’s a crosstab?) and learning so much from the Computer Center’s Social Science User Services, the head, Judith Rowe, offered me a job as a counselor for social science computing. This led to precepting a politics department public-opinion course.

Fourth, having succeeded in drafting my thesis on white-collar work on computer cards, I often marveled each time I needed a copy that, by simply giving one command, I could generate and print a complete copy of the 300-page tome! And I mused that if I had only figured out long ago that single command (which I’ve now forgotten), it would have saved a lot of time.

Fifth, as an assistant professor at Smith, I would return to the familiar haunts of the Princeton Computer Center when the sophisticated computing – e.g. discriminant analyses – needed for my first book on the white-collar working class required more computing capacity than the Smith or UMass machines could as quickly handle.

Finally, when I was teaching social science statistics, I would always remind my students to be fearless of using the computer: Their programs could not break the million-dollar machine. Yet one night the IBM 360 went down, and checking the bulletin board for the posted report on breakdowns, I found a cryptic comment: The cause was a program by a user – yours truly. Fortunately, it was fixed shortly afterward, just a long-standing reminder of Murphy’s law.

Susan P. Chizeck *75

7 Years AgoLate Nights and Punch Cards

The Computer Center was in the basement of a building on Prospect, and women were not allowed in after 11 p.m. But I had work that could only be done at night when rates were much lower, so a few of us women got them to rescind the rule, since it made little sense. At that point there were mostly punch-card machines and a few terminals that were little used. I had my data on big reel tapes that had to be mounted for my programs to run. It made sense to make friends with the computer operators, so they would see that my tapes stayed mounted. Also, the geologists were using huge amounts of run time with their geophysical fluid dynamic analyses (which was climate science), so you had to make friends with them. Then they would allow you to run your punch cards through before they submitted their jobs that would take up the machines for hours. When the results came through, they printed out on green-striped paper with spool holes.

Many of us worked all night, then the center closed at 6 a.m. We went out for breakfast and back home to sleep a lot of the day in preparation for the next night’s computer work. The night denizens were mostly consultants buying time on the University computer, students with lots of data like me, and scientists needing long run times.

Vance W. Torbert III ’68

8 Years AgoComputing Center’s Early Days

Re the Dec. 6 From the Archives photo: Back in the early 1960s, there was great excitement when the EQuad got a new IBM System 360 (they put a sign on it that referred to it being “très sexy”). As a politics major, I got access to the IBM 7094 by doing some fairly interesting multi-dimensional scaling from Professor Harold Schroeder in the psychology department, who was studying the structure of (political, among other) decision-making. I remember carting an entire 2,000-card box in the front basket of my bicycle from Blair Hall across the campus in the cold winter, hoping the data would load and the program compile. When we finally got things ready to go, we had to run it “overnight” because it required four hours to produce a carton and a half of data. Great stuff, of course, but substantially different than a K&E slide rule.

Martin Pensak ’78

8 Years AgoComputing Center’s Early Days

Back in those “good old days” of computing, a lot of the small computing jobs were too small to bother accounting for, e.g., no account required to run them. The University was very obliging to allow some local high school students to use the Computer Center as well. Not only did I go on to become a University student, computers became my entire career — so that early start was a wonderful thing for me. I have fond memories of the place!

David Hochman ’78

8 Years AgoComputing Center’s Early Days

In the mid to late ’70s, campus computing for the most part was already on an IBM 370 mainframe that fed hundreds of dumb terminals, via a time-sharing operating system. However, there was also a legacy computing environment still in use: an IBM 360 mainframe that ran in “batch” mode. You submitted a “job” not at a terminal but instead via a deck of punch cards. The Computer Center included a room full of keypunch machines; a common area with an IBM “line printer” fitted with cheap, large-format paper; and a closed room where the operators could fit a printer for special jobs.

Any student qualified for unlimited time on the 360, and so that’s what I used. As a history major, I didn’t have much need for computer programming, but I was interested in word-processing my thesis, thinking it would give me flexibility to edit up to the last minute. So I have the unique experience of having assembled an entire history thesis from text entered on punch cards in a long-defunct word-processing language.

I transported my “deck” between dorm and Computer Center in a cardboard card box stuffed in my backpack. Then, as now, backups were important, and every few days I instructed the system card punch to generate a complete set of backup cards. When my thesis deadline arrived, and my text was final at last, I ordered a custom print run on white paper, and that’s what I took to the thesis bindery on Witherspoon Street.

Steve Sashihara ’80

7 Years AgoFond Memories of the PUCC

I have fond memories of the Computer Center. I worked from freshman year through graduation in "the Clinic" (aka PUCC aka Princeton University Computer Center Clinic) with fellow undergraduates under fulltime staff managers Liz, Verna, and Diane.

We served from a free walk-in clinic on the first floor. The upper floors were locked to mere mortals like me, as they were the domain of the deities ... uh, I mean the professional staff of the center ... folks like Lee and Malinda, Bob, I.T.C, and others. The basement held our two mainframes: the batch 360/91 and the timesharing 370/158.

Our job was to help users with a wide range of problems -- often related to JCL (Job Control Language) -- the somewhat arcane // and /* cards that surrounded one's program. Users would also ask for help debugging their FORTRAN (and other language) programs. The users were mainly faculty and grad students -- definitely hardcore nerds like us.

I recall falling asleep many times in the basement of the Computer Center waiting for my jobs to run, and waking up not knowing what time it was -- although sometimes other "regulars" would kindly place my printouts from the shared printer next to my sleeping body.

We occasionally have mini luncheon reunions, and if you are a clinic alum, select that on our PU online profile, and one of the organizers may reach out to you.