Battle to control the Texas frontier

S.C. Gwynne ’74 traces the life of a Comanche warrior

Imagine writing a book on Thomas Jefferson and stumbling upon Monticello, intact but abandoned. Sam Gwynne ’74 had such an experience when researching his book about Quanah Parker, the legendary leader of one of the fiercest Native American tribes. Wandering back roads in Oklahoma, Gwynne stopped at a dusty Indian trading post and eventually found the 10-room “Star House” Parker had built on a reservation in 1890.

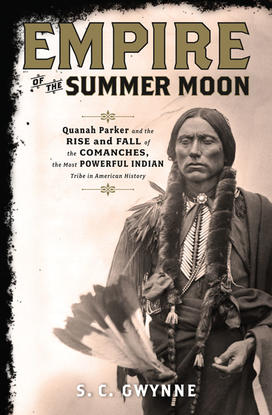

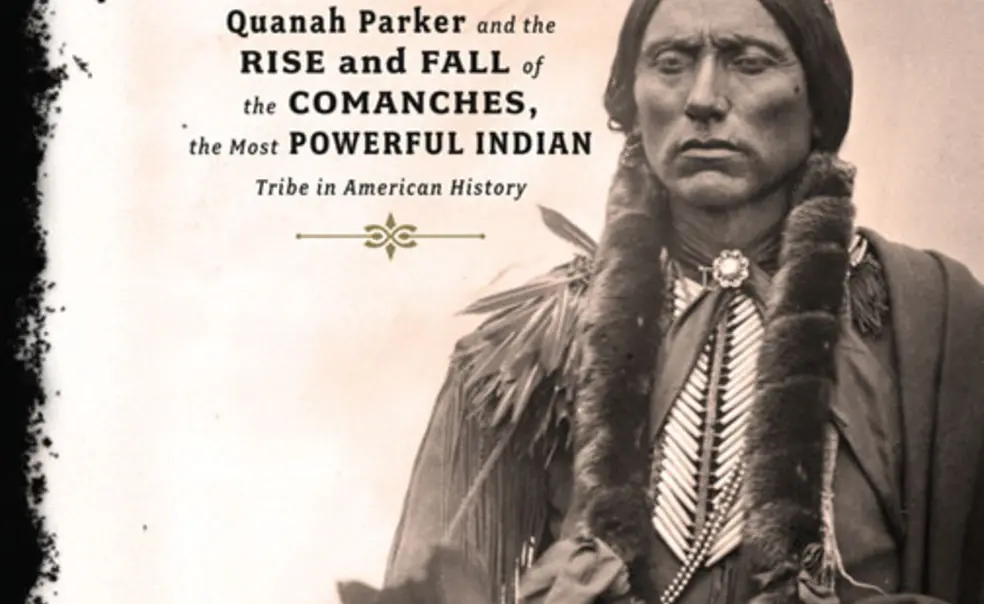

In Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History (published by Scribner this month), Gwynne tells the story of Parker, the last chief of the Comanches, and his nomadic tribe. The tribe controlled a quarter-million square miles of Texas and the Southern Plains for about two centuries, until the late 1800s. With their fast horses and deadly bow-and-arrow weaponry, they stopped the Spaniards, Mexicans, French, and Texans from expanding into their territory, and their raids depopulated parts of Texas as settlers fled east for safety, says Gwynne, a special correspondent for Texas Monthly and Time magazine’s Austin bureau chief in the 1990s.

Born in 1848, Quanah Parker became an imposing, charismatic war chief, leading raiding parties that Gwynne recounts in gruesome detail. The Comanches’ war with the Texas Rangers and the U.S. Army involved mostly guerrilla warfare, merciless encounters in which Comanches tortured their captives and the U.S. military wiped out Indian villages.

“We have a romanticized version of the West through movies,” says Gwynne. “I wasn’t prepared to learn how brutal the frontier was, and yet the white settlers kept on coming.” What drove them? “Eternal optimism,” Gwynne says: “The neighbors’ place was burned down and the women raped, but that won’t happen to us.”

By the 1870s, the Comanches reluctantly surrendered to life on reservations. They were worn down by disease, the slaughter of the buffalo herds essential to their nomadic lifestyle, and the improving weapons and tactics of Civil War-hardened army commanders who would accept massive casualties to defeat the Native Americans.

No responses yet