I have asked all sorts of people who know Bradley, or know about him, what they think he will be doing when he is forty. A really startling number of them, including teachers, coaches, college boys, even journalists, give the same answer: “He will be the governor of Missouri.” The chief dissent comes from people who look beyond the stepping stone of the Missouri State House and calmly tell you that Bradley is going to be President…Edward Rapp, Bradley’s high school principal, once said, “With the help of his friends, Bill could very well be President of the United States. And without the help of his friends, he might make it anyway.” –John McPhee, ’53, A Sense of Where You Are, 1965

June 16, 1999 At 10 A.M. on a Wednesday morning, I’m standing on a street corner in one of the blighted sections of East Los Angeles awaiting the arrival of presidential candidate Bill Bradley ’65. Two minivans swing around the corner, and a group of reporters and cameramen, gathered in a nervous huddle on the sidewalk behind me, break for the lead van, arriving just as the side door slides open. Bradley is still unpacking himself from the van’s middle seat when the first reporter calls his name. He doesn’t flinch.

“No questions,” an aide says. Bradley emerged from the van and lopes through the small crowd, his head on a different plane from the cameras and microphones, to an open door across the sidewalk. A moment later, the entire group has squeezed itself into the colorful main room of Para los Niños, a bilingual childcare center for low-income families. As Bradley disappears into a back room, the cameras establish a tight perimeter around a little group of children and their parents who have come to hear Bradley speak about child poverty.

Para los Niños is the kind of site that most serious presidential candidates dutifully visit in states like Iowa and New Hampshire and ignore in states like California. Modern presidential campaigning follows a predictable formula: run ads, raise money, and hold big speeches in the largest states; hold discussion groups and interact with the voters only in the states where word of mouth can make a difference. But on this, Bradley’s first campaign trip to California, he has spent a majority of his time in groups this size or smaller. And while the broadcast media have been present at every event, Bradley has seemed reluctant to play for the camera. In San Francisco, for example, Bradley rebuffed a reporter who asked him if he could answer a quick question for the early news.

By the time Bradley reenters the room to give his speech, the rows of telegenically arranged children near the podium have been reduced to a squirming, bilingual mass. After the children sing a song, they are herded out so that the adult section of the program can begin. Bradley strides to the podium, takes out a pair of reading glasses, and then proceeds to read his speech with the intonation of a prosaic professor. His ideas are inspiring—his premise being that we can do better for our children—but his delivery is not made for this era of sound bites. The camera crews filming the event are wasting their time; not one second of the speech will appear on even the local news that night.

Early in a presidential primary, candidates usually occupy their time by trying desperately to get their faces in the paper. After all, according to a CBS news poll conducted in early August, only 9 percent of registered voters admit to paying “much attention” to the presidential race, and most voters heat tar and gather feathers for any candidate who comes around a year before the general election. But Bradley has the unusual luxury of being in a field that has already been whittled to two: him and Al Gore. Therefore, unlike non-Bush members of the Republican field, Bradley doesn’t have to bungee jump or shampoo a goat to get in the paper—although most reporters, who seem to think that Bradley is playing the Washington Generals to Gore’s Harlem Globetrotters in this primary, sometimes wish he would. After all, a Bradley-Gore race promises to hold all the no-holds-barred excitement of a debate between economists.

The children are herded back into the room at the end of the speech, and a few of them soon cluster around Bradley’s knees, gawking at this tall man in the dark suit. As Bradley bends down to talk to a little girl, the television crews pounce, and the entire group is quickly surrounded by a tight ring of camera lenses, sound booms arching like boughs in a forest canopy. The kids aren’t quite sure what to make of the cameras, but Bradley’s focus never wavers. He listens to these children with the same level of rapt attention that he has shown thousands of strangers in airports and the counties of constituents he used to greet during his annual walks down the Jersey beaches as a Senator.

This Bill Bradley, the public servant and public figure who has always somehow seemed better than his surroundings, is the Bradley that Princetonians have followed for almost 40 years. From a distance, Bradley’s life seems so anointed, so Hollywood perfect, that it’s easy to forget how much effort has gone into his achievements. The young Bradley may have been blessed with height and athletic talent, but he also spent an inhuman number of hours shooting baskets and dribbling around chairs. He earned his Rhodes scholarship with countless long nights in Firestone Library after basketball practice, and Bradley the Senator was known on Capitol Hill for working 18-hour days. It’s going to take a lot more hard work if Bradley is going to become our next President.

Of Bouncing Balls and Politics

In the car on the way to our next event one of the staff members turns to me and asks, “Do you aspire to be a journalist?” This does not qualify as flattering the press. Then again, it’s still early in the campaign—everyone needs work—and Bradley’s staff is far less experienced than that of his Democratic rival. In fund-raising, for example, Gore has enlisted big Washington names such as Terence R. McAuliffe and Tony Coelho. Bradley, on the other hand, relies heavily on a Princeton Borough resident named Betty Sapoch, who first became affiliated with Bradley’s campaign 25 years ago when she used to organize $15 dollar all-you-can-eat pasta and meatball dinners at the Italian American Sportsmen Club in Princeton. Today, running her office from her New Jersey home, Sapoch has played a key role in raising $11.8 million through June of this year, just under $8 million behind the vice-president.

Bradley is scheduled to host a quiet event to promote women’s basketball at the Santa Monica Boys and Girls Club, but everything changed about two hours earlier in the day when one of the panelists, Bradley’s friend and former teammate on the Knicks, Phil Jackson, was announced as the next coach of the Los Angeles Lakers. Our van pulls up to a genuine media circus. Everyone is here: ABC, NBC, CBS, ESPN, maybe even the cartoon network. We all pack into a small gymnasium, and the thick stand of cameras in the back of the room and rows of tape-recorder-bearing reporters make it look as though the Bradley campaign has made it to the last weeks of the general election. Of course, everyone’s here to see Jackson—offseason basketball still outdraws early-season politics.

When it’s Bradley’s turn to speak, he begins with a joke. “Some people,” he says, “think Phil signed in Los Angeles because he wanted to win another championship. Some think he signed here because of the money. But that’s not true. He accepted the position because he agreed with me that it would be part of my strategy for southern California.” It’s the second time he’s told this joke today, and it won’t be the last. Bradley then speaks for several minutes, mostly in the kind of short, snappy statements that can be easily excerpted for the evening news.

Jackson speaks next, and his tone and expression make it clear that he is amused by the irony of a basketball coach bringing attention to a presidential candidate. “Bradley’s campaign is something I’m dropping now that I have a job,” he says. The audience, which was already primed to be charmed, goes giddy. Jackson, however, speaks seriously for a moment about his friend. “When we were roommates on the road we were talking about aspirations. He mentioned politics and I gave him some grief—it was right after Watergate. ‘It’s such a dirty business,’ I said. And he looked at me and said, ‘That’s because they’re not public servants.’”

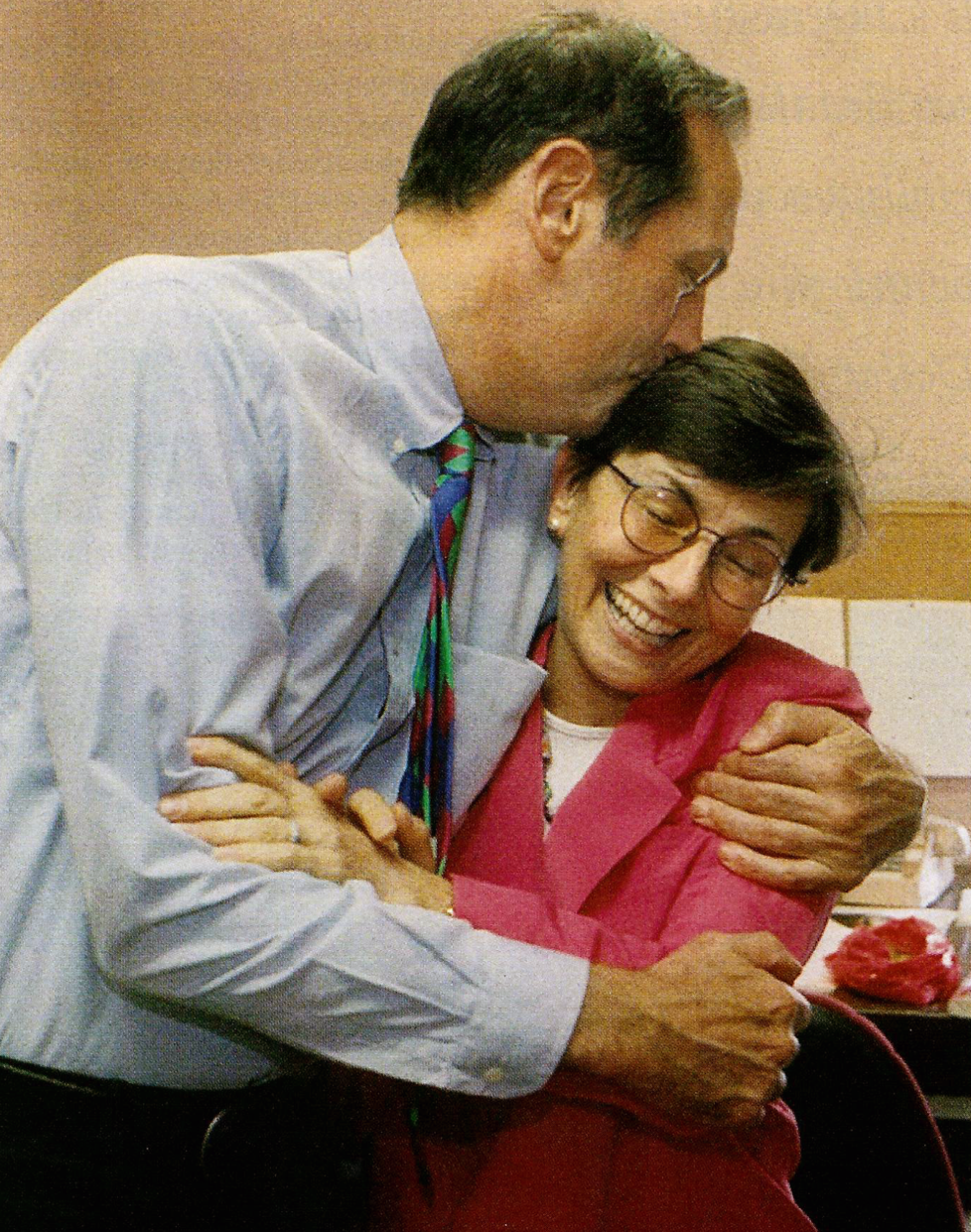

A moment later, Jackson is an entertainer again, and he jokes about how women used to throw themselves at Bradley when he played basketball, despite his ratty clothes. As Bradley playfully kicks him, I look over at Ernestine Bradley. The Bradleys met while he was still on the Knicks. At the time, she was only vaguely aware that people played professional basketball— perhaps, for Bradley, that was part of the attraction—and the two married in 1974. Ernestine is a modern political spouse: She is a college professor in comparative literature, a German-born naturalized citizen, and a breast-cancer survivor. Campaigning alongside her husband, she is intelligent and independent, and later on the trip, at a Mexican Cultural Center in San Jose, she will introduce her husband in Spanish. Today, however, she just smiles.

At Sea With the Sharks

June 17, 1999 Dinnertime in Hollywood, and a room filled with faintly recognizable faces is waiting for Bradley. Barry Diller is hosting the fundraiser, and each of the guests has paid $1,000 dollars for the privilege of drinks and dinner at the Hollywood Hilton. Despite the “little guy” rhetoric, the majority of the money for campaigns comes from a relatively small number of zip codes. Tonight’s fund-raiser will raise $800,000 for Bradley’s campaign. Bradley needs more nights like this—he has pledged not to take either any “soft money” or money from Political Action Committees. Explaining his apparent financial suicide, Bradley says, “I’m doing things a different way to restore people’s faith in politics itself.”

Fund-raising aside, it’s interesting to see Bradley in Hollywood, penny-pinching Dollar Bill in the capital of excess. In a town where people are judged by the wax jobs on their European cars, where Barbara Streisand is sometimes considered a deep thinker and a possible senatorial candidate, Bradley might be expected to play like a revival of Antigone. After all, to properly fit in with that crowd he needs a facelift and an idea drain. Two of our three recent presidents had some of that Hollywood flair. Clinton, for example, has a talent for show business—he knows how to bite his lip. Bradley, on the other hand, only bites his lip when the sheer of exhaustion of speaking gets to be too much for him to bear.

After the crowd has percolated on half an hour of cocktails, Bradley, illuminated by the white light of a television camera, comes through the door. A sound boom marks his progress through the crowd, a periscope amid the sea of Armani. While Bradley works his way around the room, I talk with an aide. Near the end of the conversation, I ask him if he has noticed a Princeton network during his time on the campaign staff. “Well,” he says, “it seems like every event we do there’s some tall guy from Princeton who played basketball.”

One of those guys is Matt Henson ’91, who played basketball under coach Pete Carril and is Bradley’s body man—basically the Jeeves of the campaign staff. Another of those guys— albeit not so tall—is Richard Wright ’64, the national finance director for Bradley’s campaign. Wright played with Bradley on the Princeton basketball team, and the two have remained close. Like Betty Sapoch, Wright has raised money for several statewide candidates and possesses a squeaky-clean reputation, but he has no experience in a national race.

Henson and Wright represent the two most visible pieces of the Princeton net, which together with Bradley’s basketball connection has helped Bradley overcome some significant obstacles. Candidates, like Bradley, who play by the letter of the law in campaign finance, need a lot of people to give the $1,000 maximum. That Bradley can host a fund-raiser in Michael Jordan’s restaurant may mean a lot of money for his campaign, but being attached to the Princeton Rolodex can pay big dividends. After all, Princeton’s unusually high annual-giving rates prove that graduates are willing to give money to causes they consider worthy.

Dinner is in the Hilton’s ballroom, which, with its mix of glittering chandeliers and slablike sound tiles, looks ready to host a Teamster convention. As dessert is being served, Barry Diller, Phil Jackson, and Ernestine Bradley introduce the candidate from a podium at the front of the room. All of them try to capture part of this man who would be president, and their efforts are refreshing. Diller, speaking first, says, “We are here to follow a good and decent man who is comfortable in his skin and certain of his moment.” Jackson, who earns a round of enthusiastic applause from the audience, tells a story about working with Bradley at a basketball camp for the Oglala Sioux in 1972. “I knew then,” Jackson recalls, “that he was going to be a person who used government to help the poorest and neediest in our society.” Ernestine, despite sharing one adjective with Diller, is the most direct of the three. “Bill,” she says, “hasn’t lost his goodness and kindness. He is sincere—his positions come from his heart, not focus groups.”

When the introductions are finished, Bradley stands to warm applause. For the fourth time that day he tells the Jackson joke, which doesn’t endear him to the press corps, but earns polite laughter from the audience. The remainder of the speech goes brilliantly. Bradley has worked hard on improving his speaking style—especially since his somniferous, C-SPAN-ready performance at the 1992 Democratic National Convention—and tonight it shows. Near the end of the speech, he reaches for eloquence. “I’ve been on the road in America for 30 years,” he says. “Over those years, I’ve gone up to strangers and asked them to tell me their stories. And those stories have told me who the American people are. The American people are a good people— there is goodness in each of us.”

Bradley has obviously thought about the role of the media in a modern campaign. Henshon will later tell me, “We want to avoid that thing where the press builds a candidate up and then tears him down,” and Bradley himself, in his book Time Present, Time Past, writes “Too many reporters think the search for the lurid and the sensational is their job…Write a thoughtful analysis of the American predicament, and it will be reduced to 30 seconds, if it makes the TV news at all.” Given that he understands the realities of that environment, it sometimes seems curious that Bradley decided to run. In 1996, when some people thought that Dick Cheney might run for president, a friend of his, explaining why he wouldn’t run, said, “You have to be a little crazy to run for president. And Dick Cheney doesn’t have a crazy bone in his body.”

Neither, of course, does Bradley. When reporters ask him—as they do at every possible opportunity—why he’s running for president, he usually gives the same response. “You run because you think you can improve the lives of millions of Americans.” And sometimes he says it in such a way that you know he realizes exactly how high the cost of running might be.

On Top of the Hill

June 19, 1999 On a Saturday morning in San Francisco, roughly 150 people who have contacted the campaign via e-mail crowd into a small theater in the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House to meet the candidate. Bradley, who has worn a dark suit every other day, arrives in a red sweater vest that makes him look a little bit like Mr. Rogers. The discussion that follows is a comforting reminder that despite all the obvious flaws with our political system, democracy isn’t dead yet. The audience is informed, asks intelligent questions, and listens intently. Bradley seems to feed off the energy, and aside from his habitual use of the phrase “quite frankly,” he is more Demosthenes than Dole—Bob, that is—this morning.

Near the beginning of the discussion, he outlines how he thinks the next year will unfold. “This campaign will have three phases,” he says. “Phase one is that ‘Bradley can’t raise any money.’ We’re about to prove that wrong. Phase two, in September and October, will be that ‘Gore is unbeatable.’ But in phase three, around December or January, it will dawn on people that ‘Bradley can actually win this thing.’ That’s what we’re preparing for.”

A few questions later, while answering a question on abortion, Bradley notes that Bush, who is pro-life but claims that the country isn’t ready for anti-abortion laws, is actually straddling two positions. “We need a candidate,” Bradley says, “who is skillful enough to point that out. Like I just did.” He pauses. “Thereby proving…” As a small, wry smile spreads across his face, the crowd chuckles.

When a man asks the inevitable question of why people should vote for Bradley rather than the vice-president, Bradley answers him in several parts. First, he claims that he and Gore have a difference in leadership style. “I try to take a big, complicated issue and put a frame around it,” Bradley says, perhaps referring to his greatest success in the Senate, the 1986 Tax Reform Act. “The vice-president was more cautious.” “

I also take risks,” Bradley continues, “like speaking on race. Sometimes people tell me I should be more cautious, but I say, ‘Yeah, but that’s the risk of leadership.” Another man, this one in his mid-20s, asks Bradley how he can win in an era of sound bites. Bradley smiles, and then gives an unexpected answer. “You can say volumes in two minutes if you think about what you’re going to say,” he says. “The Internet is a secret weapon. It provides a level of communication with politicians that’s the antithesis of sound bites. But I can play the soundbite game—I think you can be authentic, brief, and clear. Not a poll-tested, distilled version of yourself.”

The conversation continues, but I stop taking notes and watch the crowd. As times over the past few days, Bradley’s quest has seemed almost quixotic—that he is more indulging his fantasy of running for president the way he thinks it ought to be done than running to win. But today, listening to him quietly repudiate the Dick Morris method of finger-in-the-wind politics, his campaign seems both nobler and more practical. Whether you agree or disagree with Bradley’s political career has been a model or promise unfulfilled, it is undeniable that he has thought as long, as hard, and as seriously about politics as anyone running for office today.

On the way to the next event, the two vans stop in front of Big Nate’s Barbeque in the Mission District of San Francisco—apparently on the recommendation of a city councilor in Bradley’s van. Henson, Bradley, a strategist for ABC, and I go in. Bradley orders first. He pays with his own money, and quietly takes his ribs to the back of the room while the rest of us wait for our pork sandwiches. I want to make a note, so I open the book I’m holding, Time Present, Time Past. I’ve been reading Bradley’s memoir, widely praised for being a serious examination of American politics, for several days. The book owes much in both writing style and craftsmanship to the writer who once etched an indelible description of the 21-year-old Bradley, John McPhee ’53. Today, more than ever, the two Princetonians—and close friends—seem linked. McPhee writes serious, intelligent, and lengthy pieces for the magazine and book industries that increasingly value flash over substance. Bradley, for his part, is at the mercy of that media, which rather than printing a book-length profile would instead prefer to wait and hope that he does something it can splash across the front page.

Oblivious to my stare, Bradley eats his ribs and enjoys one of those few moments when nobody is asking him for anything. But the unavoidable irony is that with a little help from his friends, this very private man, who has lived his life in the spotlight, might hold the most public of all.

This was originally published in the October 9, 1999, issue of PAW.

0 Responses