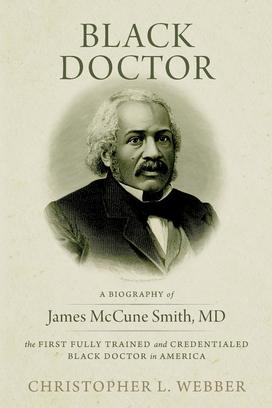

Christopher Webber ’53 Explores History of Key Abolitionist

The Book: Dr. James McCune Smith is an understudied figure of American history. He was born into slavery in New York City but managed to receive a good education at a Quaker school. He was turned down by colleges because he was Black, and so, supported by funds from his pastor, he studied in Scotland, where he earned a B.A., M.A., and M.D. Upon his return to New York, he established a medical practice that treated Black and white patients. In addition to this role, Christopher Webber ’53 explores how Smith played a pivotal role in the abolition movement, working with people like Frederick Douglass. Smith even came to chair the Radical Abolition Party, the country’s first Black American to hold such a position at a national convention. Black Doctor (Western New Mexico University) is a close look at one of the most important — and overlooked — voices of the abolition movement.

The Author: Christopher L. Webber ’53 is a priest of the Episcopal Church, having served parishes in New York and Japan. He obtained his degree from Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs. His writing career began much later in his life, and he has produced a wide range of books, from hymnals to prayer collections to his most recent book on Dr. James McCune Smith.

Excerpt:

Chapter One

Growing Up Black in New York

1813-1832

Born in Slavery in New York

Lavinia realized she was pregnant in mid-October 1812. She was only surprised that it hadn’t happened sooner. Her owner had brought her and her three older sisters north as his slaves eight years earlier, but one by one the three older women had left, fleeing south to be with family. North or south made little difference in those days since slavery was still as legal in New York as it was in South Carolina. So Lavinia, at age eighteen, was left alone with her owner, Samuel Smith, who had come to New York to make money buying and selling cotton. Unfortunately, he wasn’t very good at his trade. After eight years, he was living in a battered apartment in the worst part of the city and coming home drunk to beat Lavinia. She could put up with it for herself, but she had made up her mind not to raise a child in that environment.

He came home drunk the day she knew she was pregnant and went upstairs to get his whip. “Come up here,” he yelled. She faced him from the bottom of the stairs. “If you dare touch me with that lash, I will tear you to pieces,” she said. He stopped, stunned, but he could see she meant it. He was a good deal bigger than she and could whip her easily, but he wouldn’t fight her. He slunk down the stairs and out the door, dropping the whip on the doorstep. She found out later that he had rented another apartment a few blocks away, but she never saw him again.

James McCune Smith was born six months later on April 18, 1813. Technically, he was a slave and so was his mother, but his father knew better than to assert any claim to ownership. He may never have known that he had a son. But James knew who his father was and entered the name “Samuel Smith, merchant,” when he arrived at the University of Glasgow and had to provide his father’s name on an official form.

So Smith’s father was white and so was his mother’s father and, of course, his father’s father. Years later, when Horace Greely, a well-known New York publisher, wrote that Black Americans should go back to the land of their “forefathers,” Smith corrected him. Referring to “the hundred thousand whites who will pass this night in the embrace of Black women,” Smith asked, “Did you mean ‘foremothers?’” Smith’s mother and grandmothers were Black, but his forefathers were white and of European ancestry.

James McCune Smith described his mother as “self-emancipated.” Some slaves managed to buy their freedom. Lavinia simply asserted hers. But if she was to be free, Lavinia Smith had to find a way to make a living. Samuel Smith had not been a great breadwinner, but he had kept a roof over their heads and food on the table. Lavinia, at age eighteen, had never had to support herself; she did the laundry and the cooking, but she was a slave and she worked for her owner without being paid. What could she do now with a child on the way?

Lavinia talked to her friends about it. The Five Points neighborhood had a reputation as the worst in New York, but friends in such a neighborhood support each other, and Lavinia had friends who told her she could make some money by taking in other people’s laundry. She also knew how to mend clothes, and she could do that for pay as well. New York City was growing fast and some people were getting rich. They could afford to pay someone else to do their laundry and mending. It wasn’t easy work, especially in the months just before and after James was born, but Lavinia could do it and she could eke out a living for herself and for the baby.

It was never easy. Years later, James would write an essay about a washerwoman that would give readers a glimpse of his life in those days. He didn’t identify his mother as the washerwoman, but it seems to be her life that he was exactly describing. He wrote like an eyewitness about a woman whose apartment was filled with wash tubs and drying clothes. He wrote about the sound of the iron being dunked: “Dunk! Dunk! Goes the iron, sadly, wearily, but steadily, as if the very heart of toil were throbbing its penultimate beats! Dunk! Dunk! And that small and delicately formed hand and wrist swell up with knotted muscles and bursting veins!”

Smith also described a “good-for-nothing looking, quarter grown bushy headed boy” in the apartment, “a shade or two lighter than his mother,” who had to be called several times before he sprang into action to put more wood on the fire, light another candle, or bring a pail of water. It is not hard to imagine that the boy’s name was James and that the scene witnessed by that boy was the scene remembered and described in an essay some 40 years later.

The Neighborhood

Hester Street, where James and Lavinia lived, was in the Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan, named for the way several streets came together and made five corners instead of the more usual four. There had once been a small pond there that was a source of water for the city. Tanneries and similar businesses that needed water had been built on its shore, but gradually the pond was filled in and houses were built there. As time went by, the houses built on the soft soil of the former pond shifted and sank and were abandoned by people able to afford something better. That left the sagging remnants to the poorest residents of the city: the free Black population and a growing Irish population. Contemporary observers commented on “the crowded and filthy state” of the area and “the intemperate, dissolute, and abandoned, habits of the inhabitants . . . the proverbial filth of the streets, as well as the houses” or, in summary, the “appalling environment.”

Charles Dickens visited the Five Points on his American tour in 1842. He climbed up dark staircases, opened doors into dismal apartments, and he wrote that “all that is loathsome, drooping, and decayed is here.” Lydia Maria Child, who served as editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard from 1840 to 1843, visited the Five Points at about the same time, not long after James and Lavinia had moved elsewhere, and compared it to an “open tomb.” “How souls or bodies could live there I could not imagine. . . . There you will see nearly every form of human misery, every sign of human degradation . . . oh, it made my heart ache for many a day. . . . What a place to ask oneself, ‘Will the millennium ever come?’”

None of that, of course, tells us anything about the residents themselves who would certainly have preferred to live elsewhere had it been possible. But it was not possible, and the inevitable frustration was expressed in a variety of ways. For James McCune Smith and his friends, one way was to form alliances with friends and clash with rival groups. Children growing up in the Five Points had to fight to survive. Parents often accompanied their children to school to protect them, but the children also learned to defend themselves and some of those who survived the challenge of such a childhood went on to make a difference in the world outside the Five Points.

The Five Points was a dreadful neighborhood, but years later what Smith remembered about it was the thrill of competing to survive. Smith was never a big man, but he had friends who were older and bigger and stronger, and he was happy to go into battle with them on his side. Philip Bell was five years older and would be a lifelong friend. He would grow up to be a newspaper publisher and editor. George Downing, who later built up one of the best-known restaurants in the city “fought his way through gangs of insulting white children, and leading other colored boys he sometimes drove the white fellows from the street.” Ira Aldridge, who would become a famous Shakespearean actor, was six years older than James and apparently a leader in those neighborhood clashes.

Smith recalled a knock-down, drag-out fight on a corner of Hester Street between Aldridge and a boy called Joe Prince in which one — probably Prince, but he doesn’t say — was badly beaten. There also seem to have been clashes between neighborhood gangs, sometimes Black versus Irish, “sprinkling our young, hot blood along the streets of New York.” Smith recalled how he and Aldridge had been involved in “many a heady fight amid the memorable marshes of the classical Collect [Street]. Little did I think when his fine eye flashed and his trumpet voice cheered us on to the conflict of stones and clubs, that the same eye and voice would one day raise a shrill of admiration in an enlightened and polished audience.” To use a well-worn phrase, it was “a rough neighborhood” and one not likely to produce polished actors, successful restaurant owners, and skillful doctors. But environment can work to shape character in a variety of unexpected ways. Smith and his friends learned early on to enjoy the challenge of a fight and not to worry about the odds.

Excerpted from Black Doctor by Christopher L. Webber. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“This is an important book.” — John R. Kaufman-Mckivigan, professor of history at Indiana University Indianapolis

“A thoroughly griping life story of rising from ashes and becoming a true trailblazer. This is the important unsung history of Dr. James McCune Smith — READ IT.” — E. Lisa Forte-Mason, warden of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church

No responses yet