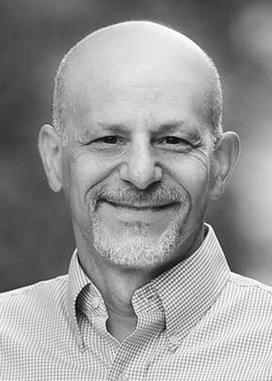

For the vast majority of us who ever played the game, the prospect of a missed college football season has absolutely nothing to do with lucrative TV contracts, bowl games, or NFL draft picks. My own playing days on Princeton’s now-defunct varsity lightweight football team were as “small time” as it gets. But while I applaud the Ivy League’s wise early decision in July to put all intercollegiate sports on hold because of COVID-19, more than four decades after my own last season on the field, I also appreciate in a very personal way what today’s students have lost to the pandemic.

After spending more than a decade of autumn afternoons and evenings watching me from the bleachers, my parents had to miss that last season of mine in the fall of 1979. My father was in the final painful months of an inexorably losing battle with pancreatic cancer and was in too much pain to travel to games from our Manhattan home.

Of course, it’s not as simple as it once was to write about football as a joyful, life-affirming experience in light of all we now know about its impact on so many players’ long-term health. Yet I still feel grateful not only for the many seasons of sandlot, high school, and college game days that we shared as a family, but even for the ones we didn’t share once my dad fell ill, dramatically enough, on the day of our big Army game the previous fall of 1978.

Playing football was hardly the most likely passion for those of us who grew up in the progressive, apartment-dwelling enclaves of financially strapped New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For some of us, in between going to Hebrew school and Broadway shows, our extracurricular lives revolved around the autumn, when we could knock one another down with great enthusiasm, if somewhat limited impact. Few of us ever went on to play even at the small Division III college programs that occasionally sent me recruiting letters.

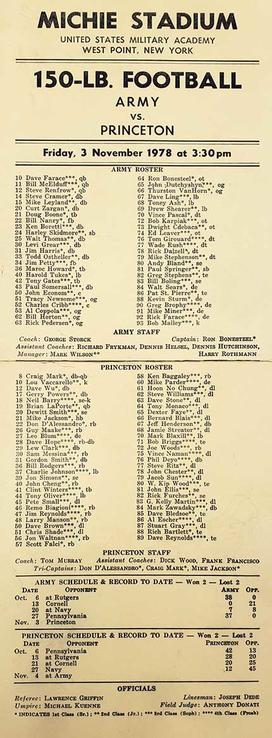

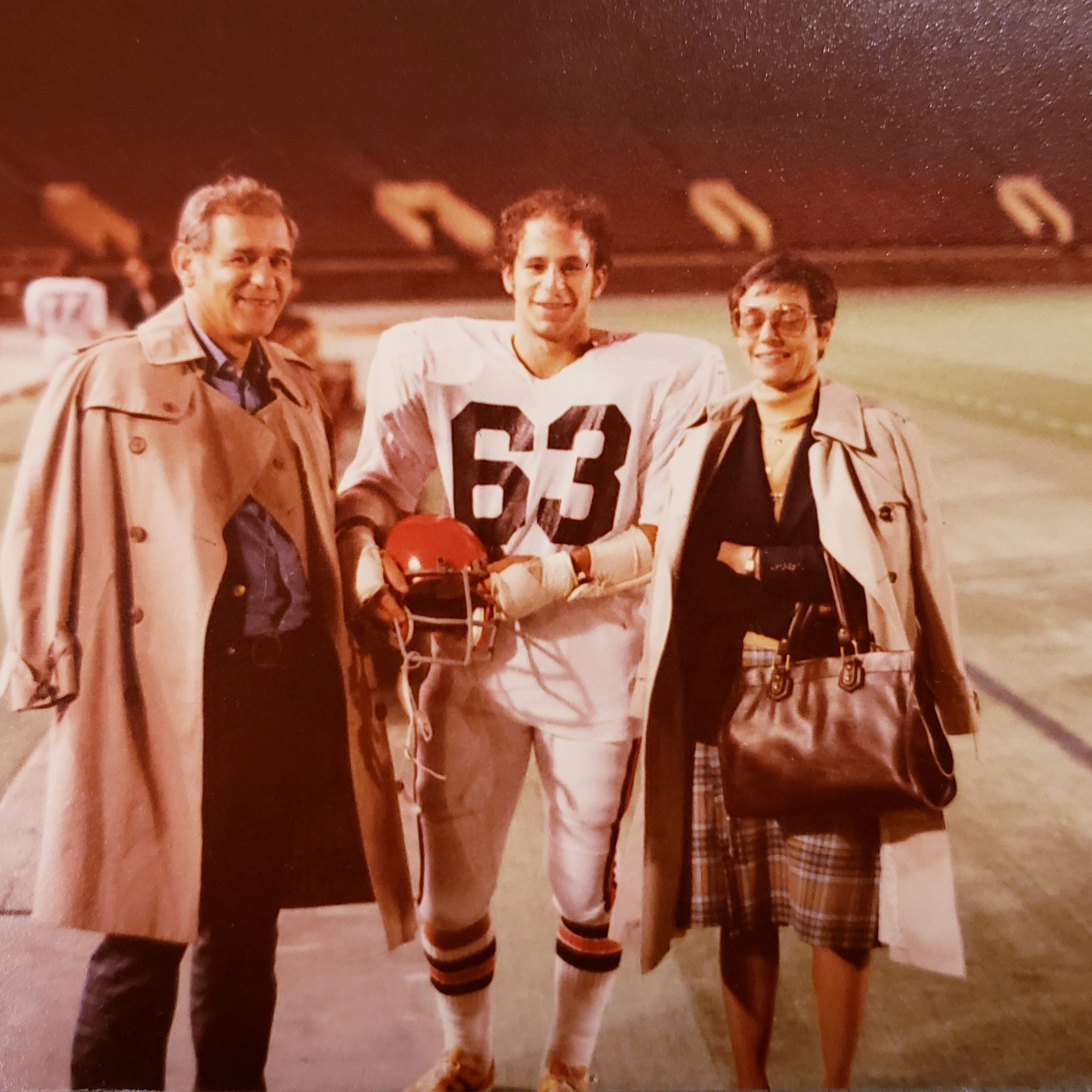

Princeton’s lightweight program offered the chance to continue playing the sport I loved. And it was fun for my parents to see me compete in iconic venues like Franklin Field at Penn, which is where the last photo of us together was taken by my big brother after a winning game. So it was strange and confusing when, near the end of my junior season, my parents didn’t show up on an early November Friday afternoon for a critical game at West Point’s Michie Stadium. In that ancient era before constant connectivity, I could only scan the visitor stands and wonder why they weren’t there with the other team parents on that perfect autumn day barely an hour up the Hudson from our home.

It was especially odd that my dad wouldn’t have come to see me play at Army. Growing up, I often heard him describe his own happy childhood memories of a favorite uncle taking him to see some of the great Army teams of the late 1930s and early ’40s. Even in the mostly empty stands for our lightweight contests, it was always special for my father to see me run into the same stadium as the great Heisman winners of his youth.

As it turned out, my parents missed an exciting late-season contest that included the only touchdown of my collegiate career when I managed to block an Army punt, then pick up the bouncing ball and carry it into the end zone. We nearly pulled off a rare victory over one of the service academies, which had rosters of lean, fit cadets and midshipmen for whom being in fighting shape was literally part of the curriculum.

Only later would my parents get fleeting glimpses of that touchdown moment, courtesy of the blurry snapshots taken by a teammate’s excited father. On the bus back to Princeton that evening, I still had no idea that my father had been rushed to Mt. Sinai Hospital that afternoon with an unknown ailment that would be diagnosed as pancreatic cancer. At age 50, he likely had only a few months to live.

The rest of my junior year would, for my father, be filled with intense physical pain and, for those of us around him, the emotional pain of watching him suffer. I lived at home that somber summer, commuting to exciting days in midtown at a career-shaping internship at public television’s MacNeil/Lehrer Report. I was also preparing for a football season I wasn’t sure I would want to play if my parents couldn’t share in it. Fact is, my father wasn’t expected to live that long. When he did, my parents didn’t want me to miss out on my last season or anything else about my senior year.

So I played, unseen by the two most familiar faces who’d been in the stands for nearly a dozen autumns. And since my father wanted to remain very private about his cancer, only a few close friends and coaches knew. Yet I didn’t feel alone. Because no matter the size of the players or the speed of their times in the 40-yard dash, like any group with an intensive shared experience and purpose, a football team can become an essential emotional support system. Of course, that can be true of any extracurricular group, from a theater cast to the orchestra. But for me at that moment, it was lightweight football.

Though my parents didn’t get to witness our improbable shutout win over Army on a muddy field back in Princeton that October (or my second blocked punt against the cadets), they at least got to hear about it. A few weeks later, I was quietly excused from practice the evening before our final home game against Cornell so I could make a quick visit back to New York. As luck would have it, I was at home the next morning to help my mother rush my dad back to Mt. Sinai for what turned out to be the last time. Then I headed down to Port Authority for the bus back to New Jersey to suit up for that evening. All season I was grateful for the pregame rituals and locker-room camaraderie that had been so much a part of my autumns growing up: the putting on of pads and uniform, the ankle-taping and eye-black (whose purpose, other than the appearance of fearsomeness, seemed limited to me).

A week later we had a final game at Rutgers. My big brother — a solid one-time lineman himself — was there; he had flown in from his first job in the Midwest for his last visit with our father. He was a superb photographer, so I still have great pictures of that final game just the two of us experienced in New Brunswick on a gray mid-November afternoon.

A few days after my own final trip to the hospital, the call I’d been expecting from my mother for the past year came to my Edwards Hall room. At 51, my father was dead. That week, I was scheduled to perform in Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party at Theatre Intime. With no understudies, we went ahead with our first show, on a Thursday, postponing the Friday performance so I could attend the funeral before returning to campus to complete the rest of the weekend run. Like my team, my fellow cast members became another campus family, playing together in an especially emotional performance under the lights of a different kind of stage.

Yes, it was an odd experience shuttling back and forth between two such different realities 55 miles apart on the Jersey Turnpike. In the sadness of my father’s death — when he was more than a decade younger than my old classmates and I are now — life back on campus was full and engaging. Whether on stage, on the field, or in class, it was so helpful to be working together — a team and a cast, classmates and faculty members, and a thesis adviser who endures as a friend and mentor to this day.

Long before the COVID pandemic took away that organic support system of campus life from students at a moment of such challenge for millions of families, I’ve reflected on how, for me and our family, playing football was the furthest thing from “a matter of life and death.” Yet in ways I never would have expected during that last season, it became an essential part of both. Four decades later, I’m still grateful for it. And it reminds me how essential it is for us to do everything we can to ensure that today’s students get to experience their own last seasons together.

1 Response

David Bledsoe ’80

5 Years AgoFootball Memories

Stoney —

Love ya brother. I remember this well. Some great memories, as you say.