Essay: Meeting Malcolm X

‘I discovered how wrong my preconceptions about Malcolm had been’

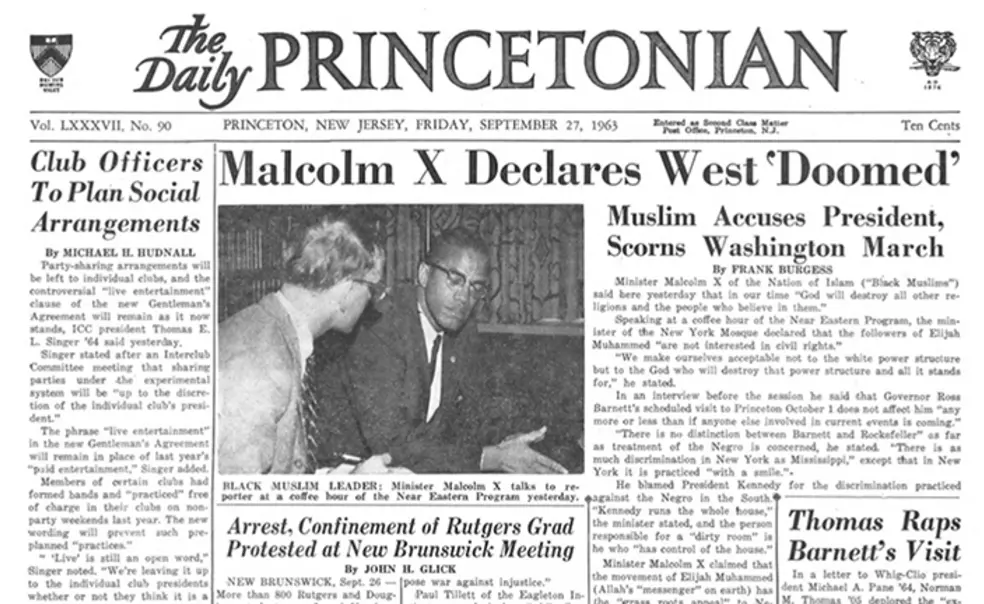

The certainty of meeting celebrities is that, sooner or later, you will find out how little you know about them. For me this happened the first time I interviewed someone of consequence. In the fall of 1963, I was an anxious sophomore trying out for the staff of The Daily Princetonian. On Wednesday, Sept. 25, the editor said, “Jones! How would you like to interview Malcolm X?”

Malcolm X? I could not imagine anything more difficult. At the time, Malcolm was perhaps the most controversial man in America. He was the charismatic public face of the Nation of Islam (NOI), the Islamic religion generally known as the Black Muslims. He had denounced all white people as evil-doers. He would be coming to Princeton that afternoon from his home in New York to speak at the coffee hour of the Near Eastern Studies Program on the second floor of Firestone Library.

This had already been a tumultuous year in the history of race relations in America, with explosive events tumbling one after another:

- On April 16, Martin Luther King had written his Letter from the Birmingham Jail.

- On June 11, Alabama Gov. George Wallace had attempted to block Black students from integrating the University of Alabama.

- On June 12, the NAACP leader Medgar Evers was shot in the back and killed in Jackson, Mississippi.

- On Aug. 28, civil rights leaders organized their first March on Washington and King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

- On Sept. 15, just 10 days before Malcolm’s visit to Princeton, four young Black girls were killed when the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed.

- The white supremacist Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett was scheduled to give a talk in Alexander Hall on Oct. 1. More than 3,500 protesters would greet him.

Everyone focuses on 1968, but the seeds of the civil rights conflict were planted in 1963.

This was the environment in which I walked into Firestone Library with Frank Burgess ’65, who was the official Princetonian reporter and a very good one. I could not imagine that the fierce Malcolm X was looking forward to talking to two preppy white kids from the Ivy League.

I could not have been more wrong. The man we met was tall, with a reserved bearing, and not angry. He sat with us and answered all of our questions thoughtfully and uncompromisingly. He did not sugarcoat his beliefs. He told us that the March on Washington was a “bourgeois” event conducted “by middle-class Negroes who aren’t unemployed and aren’t living in slums and ghettoes.” He said that the forthcoming visit of Barnett to Princeton did not affect him “any more or less than if anyone else involved in current events is coming.” He said he saw “no distinction between Barnett and [Nelson] Rockefeller as far as the treatment of the Negro is concerned.” In his view, there was as much discrimination in New York as in Mississippi, except that in New York it is practiced “with a smile.” He rejected any hope of integration with America and its fate and concluded that the U.S. government should finance the return of Black people to Africa or give them a state of their own.

What we did not know was that, at the time of our interview, Malcolm was at a turning point. He had become disillusioned with the NOI leader Elijah Muhammad and was disassociating himself from his movement. He was hard at work writing The Autobiography of Malcolm X, driving three times a week to Alex Haley’s apartment in Greenwich Village for late-night interviews for the book published after his death. Two months after our interview, President Kennedy was assassinated. Malcolm’s comment that it was “the chickens coming home to roost” led to the final break with Elijah Muhammad in March 1964. Malcolm made his own pilgrimage to Mecca a month later. At a time when his own views were becoming more moderate, Malcolm himself was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem.

Today we see Malcolm’s life through the filter of popular culture. Spike Lee’s 1992 film, Malcolm X, won Denzel Washington an Oscar nomination for best actor. Regina King’s One Night in Miami explores Malcolm’s relationship with Cassius Clay, Jim Brown, and Sam Cooke on the evening before Clay announced his conversion to Islam and took the name of Muhammad Ali.

In these movies Malcolm is portrayed as a hero. His life had played out before the celebrity era seized the public imagination. One shudders to imagine what would have been the verdict if he had lived into the age of social media. It is as a hero he is remembered.

After meeting Malcolm, Frank Burgess and I wrote up our interview for The Princetonian. I worked the night shift for the newspaper, helping prepare the article to be printed the next morning. But my life had already been changed. I had discovered not only how wrong my preconceptions about Malcolm had been, but also that journalism would be my career.

Malcolm’s funeral took place on Saturday morning, Feb. 27, 1965 at the Faith Temple Church of Christ in Harlem. Giving the eulogy, the actor Ossie Davis said, “Malcolm was our manhood, our living Black manhood!” He concluded with words that would be repeated often over time: “We shall know him then for what he was and is — a prince, our own Black shining prince, who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so.”

Author’s Note: After finishing this article, I discovered that Malcolm X’s ties to Princeton continued posthumously. His daughter Quibilah matriculated at Princeton in 1978 but dropped out. Another daughter Ilyasah spoke here in 2015, his daughter Attalah spoke in 1989 and 2003, and his late wife Betty Shabazz spoke in 1991.

Landon Jones ’66 was the head editor of People magazine at Time Inc. from 1989-97. He edited the Princeton Alumni Weekly from 1969-74.

1 Response

Carl “CB” Gebhard

1 Year AgoInteresting Story by an Impressive Alum

Lanny told me as well as other classmates from St. Louis Country Day School (now MICDS) about his interview with Malcolm X. We correspond in a monthly Zoom meeting. I knew about it already but did not realize he was an underclassman at the time. Lanny has had an impressive career as a journalist with Time, Inc. and is the author of several books. Then there is Mike Witte, who surfed in his wake as an illustrator. Our headmaster was Ashby T. Harper, a Princeton graduate as well, bringing fellow Princetonians with him to teach. As a result, my class of ’62 sent an abundance of members to your institution. Kudos also to Mike for his video sent upon his 50th reunion entitled The Serendipity of Failure.