Essay: Remembering Mercer Street

Norman L. Cantor ’64 recalls noteworthy people and scenes from 1950s Princeton

From age 12, I lived at 243 Mercer St. My mother built our family house there in 1954 at a prime location, the corner of Lovers Lane, about a quarter mile from the legendary and bucolic IAS and about a mile from Nassau Street, Princeton’s main drag. Mercer Street has a few impressive institutional presences like Trinity Episcopal Church and the Princeton Theological Seminary. But my personal recollections are most aroused by certain noteworthy people who lived on Mercer Street.

The most distinctive resident of the period was Albert Einstein. His modest single-family home on Mercer Street was across from a park where I occasionally played softball or touch football. I spotted him several times ambling along Mercer Street in a ratty maroon sweater with his unmistakable white coiffure exposed to the sun. It never occurred to me to approach Einstein. He might have been docile-looking, but I had no particular topic to address with him. Commentary on the weather would have been presumptuous with this renowned genius.

By contrast, my father Manny Cantor once entered Einstein’s Mercer Street abode and spoke with him. My father was then (1939) chair of the Mercer County Communist Party. He knocked on Einstein’s door seeking his signature on a petition urging America to avoid war in Europe. The housekeeper started to turn my father away, but Einstein heard the conversation and let him enter. Einstein listened to my father’s anti-war spiel and politely declined to sign the petition.

Another public figure who lived for a time near me on Mercer Street was a prominent historian of the Middle Ages, Norman F. Cantor *57. At that point in time (1958), Norman F. had completed his Ph.D. and was teaching at Princeton University. I, Norman L. Cantor, was then a 15-year-old prep-school student living down the same street. The two Norman Cantors did not know each other, but their similar names and street addresses led to occasional communications issues. I would occasionally get his mail, including notes congratulating me on publication of an erudite article or book. Once, Norman F. got a call from the organizer of the annual Christmas dance for Princeton teenagers. When the organizer asked him if he was coming to the Christmas dance, he replied that he would have to check with his wife. That response clued the organizer into realizing the identity error.

Though Norman L. never met Norman F. during their time of common residence on Mercer Street, that omission was cured years later. By 1978, Norman F. had become a distinguished medieval historian on the New York University faculty and I was an aspiring law professor at Rutgers. By coincidence, a woman who had served as a student research assistant for Norman F. in the history department at N.Y.U. became my student research assistant at Rutgers Law School. Deborah thought that it would be cool if the two academic Normans met, and she organized a dinner meeting at a Manhattan restaurant. While neither of us was enthused by the idea, both Normans agreed and the dinner took place. It was a polite occasion, memorable only for the impression that Norman F. was a rather dour individual. He didn’t suffer gladly people whom he thought were fools, and apparently the burden was on his interlocutor to dispel an initial presumption of foolishness.

The Norman Cantor coincidences didn’t end with Mercer Street or a common research assistant. Ten years later, in 1988, Norman F. turned up as a Fulbright visiting professor of history at Tel Aviv University where I was then serving as an associate professor on the law faculty. When I learned that Norman F. was present in Tel Aviv, I invited him to lunch. That both historian Norman F. Cantor and lawyer Norman L. Cantor had pursued an interest in Israel seemed like a striking coincidence and a catalyst for bonding. Yet the dynamic of that Tel Aviv meal mirrored our prior repast in Manhattan. That is, I recall the conversation as desultory and Norman F.’s disposition as grumpy.

Of course, my negative appraisal of Norman F. might be tinged by sour grapes, i.e., by professional jealousy. Norman F. was one of the most widely read medieval historians and his textbook, The Civilization of the Middle Ages, sold over a million copies. None of my four books ever generated sales of more than a few thousand copies even though there was burgeoning interest in my scholarly field, the moral and legal aspects of end-of-life medical care. I could only envy, not replicate, Norman F.’s appearances on the New York Times bestseller lists.

My last noteworthy recollection of Mercer Street in Princeton flows not from prominent neighbors, but from a notorious episode in that town’s history. I knew the white frame house at 34 Mercer St. well. It was the home of the Emily Stuart family. Emily “Cissy” Stuart was the divorced mother of two sons, one of whom — Donald (Jeb) Stuart — was a good friend of mine during our middle and late teen years. Jeb and I were part of a triumvirate of four youths who often hung out at Jeb’s house. Jeb’s mother was sometimes present in the house. We called her “Mrs. Stuart” not “Cissy,” and we appreciated her not so much for her articulate insights as for the snacks she frequently offered. We did know her as a strong-willed, independent woman who loved gardening and could split her own firewood.

The distinction of 34 Mercer St. stems not from any connection to me or Jeb’s other friends, but from the catastrophe occurring there on April 2, 1989. On that Sunday afternoon, Emily Stuart was murdered in the basement to which she had descended after finishing her gardening. Jeb’s 74-year-old mother was stabbed five times in the back. Despite a $50,000 reward offered by the family and despite a prolonged investigation that continued for many years, the crime was never solved. Emily’s murder constitutes one of the most notorious episodes in the history of a university town that perennially prided itself on its rarified, nonviolent atmosphere. I knew well both the victim and the crime scene.

McPhee convincingly explained the impetus for old writers to persist. (I just reached age 79.) Continued jottings, even without a consistent theme, provide a good way for writers to reassure themselves they are still alive. McPhee observes that Mark Twain wrote 750,000 words as an aging relic and that if he had stayed with it, he might still be alive. I used to think that the way to reassure myself that I was still alive was to read the morning obituaries and confirm that my name had not appeared. More fun to continue reflecting about the highlights of a bygone era.

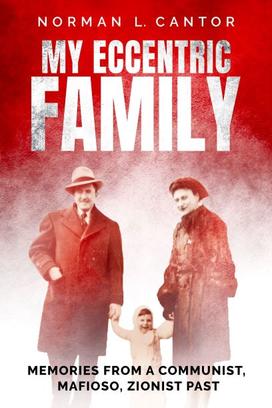

Norman L. Cantor ’64 is a distinguished professor of law, emeritus, at Rutgers University Law School. His recently-published memoir is My Eccentric Family: Memories from a Communist, Mafioso, Zionist Past.

No responses yet