Essay: Shockley Comes to Princeton

In the last six months, there have been heated discussions on campuses throughout the United States about the tradeoff between free speech and respect for all members of campus communities. Princeton faced the issue in November, when a group of students calling themselves the Black Justice League took over President Eisgruber ’83’s office and made demands related to training on racial sensitivity, race-focused housing, and the racially charged legacy of Woodrow Wilson. An article in the Nov. 11 issue of PAW highlighted the difficulties in drawing boundaries for campus conversations, and faculty expressions of opinion have come under fire at Yale, Claremont McKenna, and elsewhere.

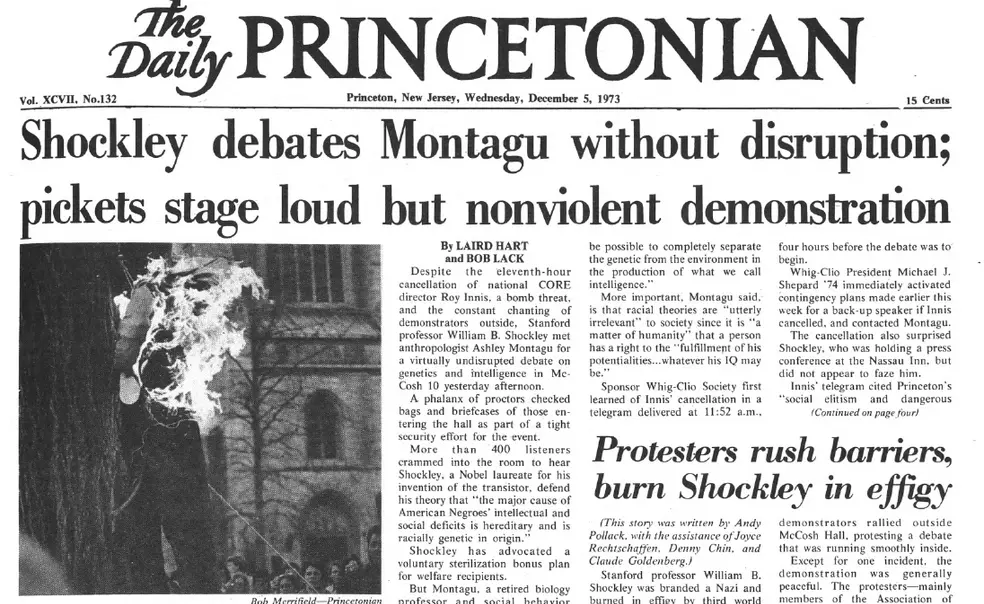

As the PAW article noted, Princeton faced a very-public example of the tradeoff between free speech and respect for minority students when William Shockley was invited to debate on campus in December of 1973. I was a sophomore member of the Governing Council of the American Whig-Cliosophic Society at the time, and the event attracted interest from news outlets throughout the United States.

William Shockley had won a Nobel Prize in physics earlier in his career as one of the inventors of the transistor. Late in life, he ventured outside of physics to study the relationship between intelligence and heredity. While the “nature vs. nurture” issue has engaged scholars for many decades, Shockley went well beyond the academic content of that debate. In a U.S. News & World Report article in November 1965, he suggested that “ inferior strains [of the population] have increased chances for survival and reproduction at the same time that birth control has tended to reduce family size among the superior elements.” In Shockley’s view, “welfare and relief programs” were counterproductive, and would only increase the disparity between the “superior [white] race” and the “inferior [black] strains.” No wonder he was controversial.

Dr. Shockley was scheduled to debate these issues at Harvard Law School against Roy Innis, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), but Harvard withdrew its invitation in response to pressure from members of the law school faculty and the Harvard Black Students Association. Whig-Clio’s Governing Council immediately extended an invitation to hold the debate at Princeton.

In truth, I was probably the least important member of the Governing Council at the time. While some GoCo members were responsible for bringing Supreme Court justices to campus or winning Model U.N. awards around the world, my role was to run the James Madison Humorous Debating Society. Our debates on topics like “Resolved: The president of the United States needs the services of a female vice president under him” and “Resolved: Nixon should have held on to Cox” featured bad puns, flowing beer, and the occasional streaker.

Although I was not involved in the decision to invite Dr. Shockley to campus, I was at the GoCo meeting where the invitation was discussed with a delegation of black student leaders. The black students were polite, but firm, and argued that it was not appropriate to invite a speaker whose purpose was to question the intelligence of African Americans as a group. They felt the entire event would be offensive and dehumanizing, and asked Whig-Clio to rescind the invitation.

A lively discussion followed, and I believe the Governing Council was unanimous in contending that free-speech concerns outweighed the need to respect the rights of any single group. There were no black members on the GoCo that year, but I was surprised to hear one Whig-Clio officer claim that another GoCo member could understand what it felt like to be a member of an oppressed minority group “because he was Jewish.” I doubt that argument would carry much weight today.

Princeton’s black community also appealed to the University administration to call for the Shockley invitation to be rescinded. In a carefully worded defense of free speech, President William Bowen *58 declined to intervene. Bowen wrote that, in his view, “neither Mr. Innis nor Mr. Shockley seems to have much in the way of professional credentials when the subject to be discussed is genetics.” He went on to argue that free speech on college campuses is critical and “although Black Americans carry with them a particular history of victimization,” no group should have “the power to determine who may not be heard or what may not be said on this campus.” Although he might find some speakers “revolting, foolish, or just plain wrong,” Bowen felt it was important “for each of us to decide individually” what we thought about a speaker’s views. The invitation would stand.

The debate itself was anticlimactic. Roy Innis of CORE dropped out, under pressure, on the morning of the event, and world-renowned anthropologist Ashley Montagu was a last-minute substitute. Professor Montagu was witty and entertaining, although not really much of a debater. In fact, the “debate” was more a case of two speakers making their separate arguments, neither with much concern for what the other speaker had to say. The packed McCosh 10 crowd cheered loudly for Professor Montagu, but it was more as a statement against Shockley’s views than in favor of any particular arguments from the anthropologist.

Outside of McCosh 10, several hundred students – both black and white – chanted and carried signs to protest the debate. The protests were respectful, and no one was prevented from entering the building or from speaking. Terry Robinson ’76, a former president of our class, stood during the debate with his back to the podium to protest the event, then walked out silently when the debate was concluded.

Virtually all of the students in attendance thought Shockley was wrong when they entered McCosh 10, and virtually all felt the same way when they left. The debate did focus attention throughout the campus on the issue, and increased intellectual engagement with the policy implications of genetic profiling. The respectful protests led by the campus’ black community reinforced that protesters also deserve free speech, and that they strengthen their own cause when they protest without disrupting others.

That was the end of the event, as reported by the press, but there was a coda for the Whig-Clio Governing Council. After the debate, the GoCo was invited to dinner in a private room at the Nassau Inn, and I am pretty sure the dinner was paid for by Dr. Shockley. I was one of about 10 GoCo members who could not turn down a free meal at the Nassau Inn, so I went. During dinner, Dr. Shockley continued to pull out charts and graphs from his various studies, to reassert his arguments about nature vs. nurture. In a room full of liberal-minded students, he generated plenty of discussion, but convinced no one.

When the dinner was over, most of the students headed back to campus. I and another sophomore somehow ended up walking Dr. Shockley back to his room at the inn. He invited us in, then spent an additional 45 minutes sitting on the edge of his bed, trying to persuade the two of us all over again that his data were correct and that their many implications should not be ignored.

To be honest, by the end of the 45 minutes, I felt nothing but pity for Dr. Shockley. Here he was – a brilliant, Nobel-prize-winning physicist – and it was somehow important for him to keep trying to convince a couple of Princeton sophomores that his controversial theories were correct. As I walked back to campus, I could only feel sorry for him.

Josh Libresco ’76 p’17 p’19 works for the OSR Group, an international marketing research company. He lives in San Rafael, Calif., just north of San Francisco.

No responses yet