Essay: Thank you, Ed Holmes *80

Princetonian recounts transfer student experience and the positive impact of her ‘Brain and Behavior’ preceptor

I can never forget my first day of class in September 1977. Our family had relocated from Cranford to Princeton and my 7-year old twin boys were not adjusting well to their new environment. I cautiously approached the classroom. My heart pounded so fast, I feared the other students would detect my heaving chest and labored breathing. I asked myself, as I had many times before, what right did I have to attend this Ivy League university? My primary job was to be a wife and mother, not to attend school and prepare for a career. My husband and children were destined to suffer because of my selfishness. These beliefs were embedded deep in my psyche.

As I entered the classroom, heads turned and I heard a student whisper, “Not just a female, but an older woman, what’s next?” I quickly slumped into the nearest available seat and tried to remain inconspicuous.

Desperately seeking comfort and any sign of affirmation, I glanced in the direction of the instructor. His face hid behind a thick, dark, unfriendly black beard. When our eyes met, his frown and look of disgust were unbearable. He quickly turned away and I surrendered to the anxiety.

The lecture was on the brain and how neurotransmitters conduct signals across synapses. I listened attentively but was lost. I raised my hand and asked the professor to define synapse. The students’ laughs, jeers, and glances stung. The professor quickly explained its definition and returned to his lecture. I asked no more questions.

My memories of that first class are few, but I do recall my tears and confusion upon arriving home that evening. I had crossed a bridge from the safety and comfort of the familiar roles of wife and mother to a world of the unknown. I came from a middle-class family and had not experienced the world of affluence and privilege from which so many of my fellow Princetonians came. They wore designer clothes that I couldn’t afford, spoke of vacations I could only imagine, attended the best prep schools, and didn’t struggle to pay for books and tuition.

As a child raised a strict Catholic in the Bronx, New York, tradition and Catholicism were the cornerstones of my family’s existence. Choices for women were limited. Like every female in my family before me, I was to graduate from high school, get a job as a secretary, find a husband, and have children. My father had told me not to study too hard because I should never let a man know I was smarter than he. My aunt Eleanor said my grades didn’t matter because no one would care about them when I walked down the aisle. I sobbed as I realized that my beloved family, no matter how well-intentioned, had buried me in their religion and choked me with their traditions.

Three weeks into that first semester, my anxiety turned to terror. My boys were still struggling and acting out in school, and our handyman’s special home needed some attention. However, I was so overwhelmed with school, I had little time for anything else. After consulting with the dean, I decided to drop the course, but needed the preceptor’s permission.

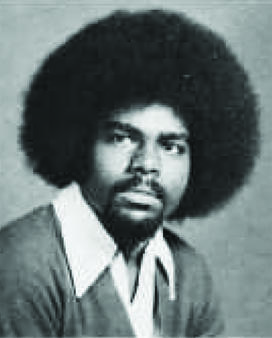

So, I scheduled a meeting with Ed Holmes *80. Upon entering his office, I was surprised to see an African American man with a huge afro. I’m embarrassed to admit that his appearance and color frightened me. Ed sat behind a large desk surrounded by books and several models of brains. I sat opposite him and waited for him to speak.

“How can I help you?” he asked. I began my plea for his permission to leave the course. As I spoke, his eyes were downcast and his face frozen, but he listened intently to each word as it spilled from my lips. He remained silent, for what felt like an eternity.

“You think the admissions committee made a mistake when they accepted you, don’t you, Ellie Vaughan?” he asked. I was stunned, shocked; not sure what to say. After a long pause, I replied “Yes.”

“And, you think everyone on this campus is smarter than you?” I again answered yes. “Well, my job is to tell you that the Princeton University admissions committee doesn’t make mistakes,” he said. “You’re here because a lot of people believe you have what it takes to succeed, and perhaps it’s time for you to believe it too.”

Ed spent the next 30 minutes telling me about what I have come to call “the Princeton mystique.” His words were kind and his empathy comforted me. He spoke of the fierce competition and enormous pressure on the students, and assured me I was not alone, as many students struggle but are not willing to admit it. His words soothed and calmed me. I wondered if he had similar experiences, but I was reluctant to ask.

As a child raised a strict Catholic in the Bronx, New York, tradition and Catholicism were the cornerstones of my family’s existence. Choices for women were limited. Like every female in my family before me, I was to graduate from high school, get a job as a secretary, find a husband, and have children.

Then he said that he would not give me permission to leave the class. It didn’t matter if I got an A, B, C, or D. I needed to complete the course for reasons other than the ultimate grade. He wished me well and assured me of his confidence that I would prevail.

I expected to be devastated, but to my surprise, I felt relief. The decision was no longer mine. Ed Holmes had realized that my reasons for leaving were just excuses. Knowing that I wasn’t alone and that I was experiencing the same doubts and fears as others brought me comfort and renewed vigor.

Ed’s kindness motivated me and I became more determined than ever to succeed. I studied relentlessly, brought books to soccer games, parties, and temporarily alienated a few of my friends. My efforts were rewarded. I got an A-plus, the second highest grade in the class behind another female student.

Unfortunately, I never personally thanked Ed Holmes for the profound difference he made in my life. I’ve enjoyed a successful career as a licensed clinical and a certified school psychologist. I became so mired in my efforts to succeed at Princeton and missed my chance. So, I’d like to do that here: Thank you, Ed Holmes, for your kindness, your wisdom, and for your refusal to allow me to make a big mistake.

2 Responses

Lita Diamond

3 Years AgoKudos to Ellie and Ed

I came to know Ellie today. We have been playing tennis together for many years and never spoke about our backgrounds. She is to be praised for her stamina and fortitude. What a wonderful article. This will be the start of her writing career. Where is Ed?

Floyd Caldwell

3 Years AgoHow a Response of ‘No’ Yielded Success That ‘Yes’ Never Could Have

Ed Holmes used resources far beyond his response to the young wife, mother, and student who was ready to give in to traditions, attitudes, and beliefs and drop a course.

Ed invoked his own life experiences, forward-thinking mentality, confidence, and mature knowledge to yield a student reborn with a sense of confidence, self-worth, purpose, and success — and he did it all with a “no.”

We so need Ed Holmes’ mentality in today’s world.