Firestone phasing out a uniquely Princeton way to classify books

Three-quarters of a million books in Firestone Library will be reclassified over the next 15 months as the library completes a switch to the Library of Congress classification system. The switch, which is part of a broader, multimillion-dollar renovation of Firestone, will erase one of the last vestiges of Princeton’s unique book-classification system, which dates to the turn of the 20th century and is named for its originator, former University librarian Ernest Cushing Richardson.

A century ago, when collaboration among libraries was more difficult, many major research libraries adopted their own book-classification systems. Harvard and Yale each had its own, said University Librarian Karin Trainer, and eventually so did Princeton. The Dewey Decimal System, which dates to 1876, was considered by many at the time to be too simple for research libraries.

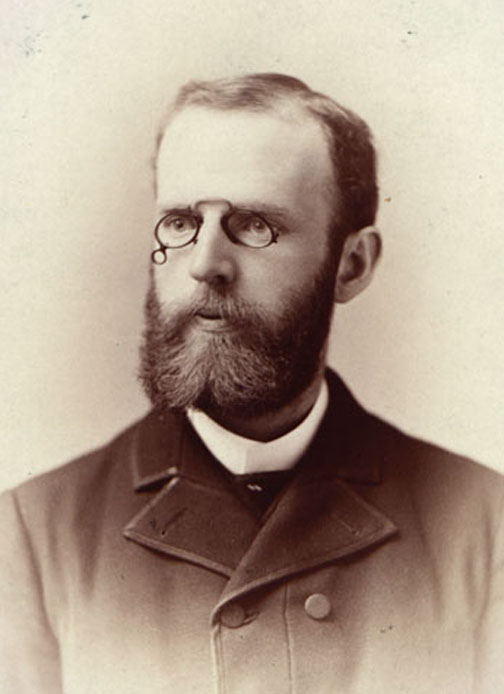

Richardson — “a librarian’s librarian,” in the words of Stephen Ferguson, the assistant University librarian for rare books and special collections — became Princeton’s librarian in 1890 and immediately set about revamping its haphazard classification system. The system that bears his name was laid out at the end of his 1901 classic, Classification, Theoretical and Practical, a book that has led library historian W.C.B. Sayers to call Richardson “the real founder of the modern study of library classification.”

The Richardson classification system, which never was emulated elsewhere, is strictly numerical, whereas the Library of Congress system, which was created in 1897, classifies books using a system of letters and numbers. Although the Richardson system was praised for its precision, it could be too precise, producing overly long classification numbers. Over the decades, the Library of Congress system has come to predominate, in part because having a single standard makes sharing books between libraries easier. As early as 1902, Richardson himself wrote that he thought most libraries in the country eventually would adopt the Library of Congress system, and that he would have done it himself had that system been invented three or four years earlier.

Princeton stopped numbering new acquisitions using the Richardson system during the late 1960s, switching to the Library of Congress system instead. One consequence is that books on the same subject, such as American history, often are shelved in different parts of Firestone. The switch, said Trainer, “will mean that students browsing in the stacks, which is something we strongly encourage them to do, will be able to see an entire subject area at once.”

Yet, as Richardson himself observed in an assessment of the Princeton classification system toward the end of his career, “Reclassification is a very expensive luxury.” The current project, which is expected to be finished by the fall of 2011, will cost $1.6 million. Work already has begun, starting with the classics section, located on the third floor, and in the Scribner Room, located on B floor.

1 Response

Benjamin R. Beede *62

10 Years AgoBrowsing at Firestone

Firestone Library users received the welcome news that the Richardson system for classifying books is on the way out (Campus Notebook, Nov. 17). The Richardson system is an inconvenience to users and probably an equal inconvenience to the staff. As the article said, Richardson deserves credit for having been a pioneer in the classification of library books, but the system’s time clearly has passed.

Even more welcome news was University Librarian Karin Trainer’s acknowledgement of the importance

of browsing in the book stacks. The organization of materials in libraries is not perfect, nor can it be. Browsing remains a highly useful tool for using library materials. Within the past few years I have made several “discoveries” at Firestone that greatly facilitated several research projects of mine. I have had similar experiences at various units of the Rutgers University Libraries.