Global Seminar Students Help Bring African Languages to the Digital Age

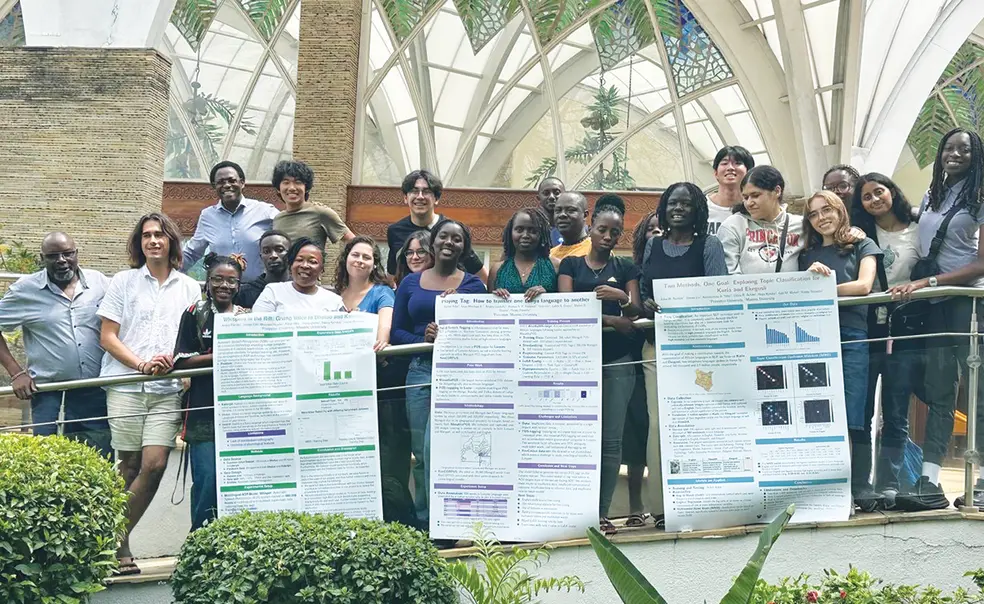

Thirteen Princeton students traveled to Kenya this summer as part of the Global Seminar “Technology for African Languages in the Digital Age,” spending six weeks studying Swahili, collecting and analyzing data in the country, and collaborating with six students from Maseno University to build digital tools for underrepresented languages.

Working in small groups, the students completed three projects related to language models: one on topic classification, one on automatic speech recognition, and one on speech tagging, each focusing on translating to English, Swahili, and one or two of Kenya’s Indigenous languages. The students also conducted fieldwork, where they visited fish markets, beaches, and community centers across the country, and took and captioned photos of culturally significant places, objects, and interactions to generate datasets.

“Not only is having the data in the language important, but having it be culturally relevant is also important,” Rachel Adjei ’28 told PAW. Most large language models (LLMs) rely on automatic translations, but the students conducted manual, on-the-ground work to ensure accuracy and nuance.

“We were really engaging with local people,” said Andrei Florian ’28.

Collaboration with the local students at Maseno was central to the experience, according to Farah Attia ’28. Each of the three groups included two Maseno students, whose linguistic and cultural knowledge shaped the projects.

For the Maeseno students, the seminar offered just as many new experiences. Hope Kerubo, a Maeseno student, found the experience transformational. “I do not think I would have ever been interested in researching on my language before this,” she told PAW. She now hopes to pursue natural language processing with a focus on low-resource languages.

According to Mahiri Mwita, a lecturer in Swahili in the Program in African Studies and one of four instructors for the seminar, the goal was to create data sets that authentically represent African linguistic and cultural identities. “Language is what carries the culture of any society,” he said. “The biggest gap that we have is that even when these large language models like ChatGPT, Gemini, and others are trying to create resources in these local languages, they don’t necessarily go to the culture.”

As the field of artificial intelligence advances, language scholars and technologists alike are growing concerned about the erasure of smaller languages, specifically in Africa.

Srinivas Bangalore, a visiting lecturer and another one of the instructors, explained that today’s technology focuses on “economically viable languages,” which are only a handful of languages out of the roughly 7,000 in the digital space. For him, languages that don’t have significant digital resources need to be brought into the fold; if they’re not, they may disappear in the real world.

“With that disappearance ... we are going to lose a lot of culture and history and traditions and knowledge,” he told PAW.

Global Seminars, credit-bearing courses offered through the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), provide an immersive learning opportunity for students to explore a topic in depth through classroom learning, local guidance and collaboration, and cultural excursions.

This marked the fourth summer that a Global Seminar took place at Maseno University in Kisumu, but the first time that this course was offered. It grew out of the freshman seminar Teaching Computers to Understand African Languages, led by Professor Happy Buzaaba, which focused on introducing African languages into LLMs. About half of the students from the freshman seminar went on to take the Global Seminar.

Mwita has played a key role in the summer program for almost two decades and, after speaking with Buzaaba, decided to center this year’s seminar on language technology in Africa.

Jordan Chi ’28, a student in the freshman seminar, said the idea of going into local communities and learning the techniques to create technologies he hoped would benefit them, even if only for six weeks, struck a chord with him.

“I would have the power to actually make something that would help the lives of people on the other side of the world from me. I think that was the moment where I realized this is something that I really wanted to do,” Chi told PAW.

The curriculum of the seminar was divided into two parts. For the first part, students learned about the impact of language technology on daily life and studied Swahili, along with exploring six other Indigenous languages spoken in Kenya. For the second part, they were introduced to natural language processing concepts and tools, including data collection, transcription, and annotation.

The program was supported by PIIRS, the Beth M. Siskind Global Seminars Fund, the Humanities Council Magic Grant, the Program in African Studies, and the Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication.

1 Response

Judith Ayuko Otieno

5 Months AgoProgram Kudos

My four years in this program have benefited me a lot.