Hidden Chapel Pulpit Honors a Civil War Friend of America

The imposing University Chapel that dominates Princeton’s central plaza was built between 1921 and 1928. It was designed by the great architect Ralph Adams Cram to replace the old Marquand Chapel and its 104-foot tower, which had burnt down on May 14, 1920, in a fire that also devoured Dickinson Hall. The new chapel was the largest such building on any American campus at the time and cost $2.3 million to build — which meant that President John Grier Hibben 1882 had to embark on a major fundraising campaign. As a result, scattered throughout the chapel’s immense collegiate Gothic spaces are memorials to its numerous donors — the Braman Transept, the Milbank Choir, even the Hibben Garden.

One of the easiest of these memorials to miss, however, appears on the chapel’s south side, where a door opens to an exterior stone pulpit bearing on one face this inscription:

IN MEMORIAM

JOHN BRIGHT

1811-1889

THE GREAT BRITISH

COMMONER AND

FRIEND OF AMERICA

IN HER TIME OF NEED

FLORENCE BROOKS-ATEN

Florence Cornelia Ellwanger Brooks-Aten was in many ways the classic wealthy eccentric. Born on Christmas Day in 1875, she spent lavishly on projects that ranged from sponsoring a contest to write a new national anthem to building a woodland estate near the Monadnock Region in New Hampshire. One of her projects in 1924 was the creation of the Brooks-Bryce Foundation for the Furtherance of Friendly Relations between Great Britain and the United States, the Brooks half of the title coming from her great-great-grandfather, a soldier in the American Revolution. And since the purpose of the foundation was to promote “Anglo-American amity,” she made the name of a famed 19th-century parliamentarian, John Bright, the center of her bequest to the new chapel — and therein lies one of Princeton’s most unsuspected connections to Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War.

Nothing held out greater possibilities for the success of the Confederacy during its brief years of life from 1861 to 1865 than the sympathies it generated in Great Britain. Britain was, after all, a monarchy, albeit a constitutional monarchy, and it looked deeply askance at the example the American democracy was setting for the peoples of Britain’s empire around the world. No sooner had the Civil War begun than British aristocrats rushed confidently to predict that the breakup of the United States would offer proof-positive of the instability of democracy. The Earl of Shrewsbury eagerly prophesied in 1861 in the Nottingham Daily Guardian that the Civil War “would show that the separation of the two great sections of that country was inevitable, and those who lived long enough would ... see an aristocracy established in America.”

Besides, Britain’s economy fed ravenously on Southern cotton, and an independent Confederacy would guarantee the flow of that cotton — all of which meant turning a blind eye to the fact that the cotton was the product of nearly 4 million enslaved African Americans. But the Navy’s blockade of the Confederate coast imposed a stiff cost on Britian’s cotton economy. For the first three years of the war, there were numerous proposals in Parliament and in the cabinet of the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, for British intervention and mediation, proposals that everyone knew would be pointed toward securing independence for the Confederacy.

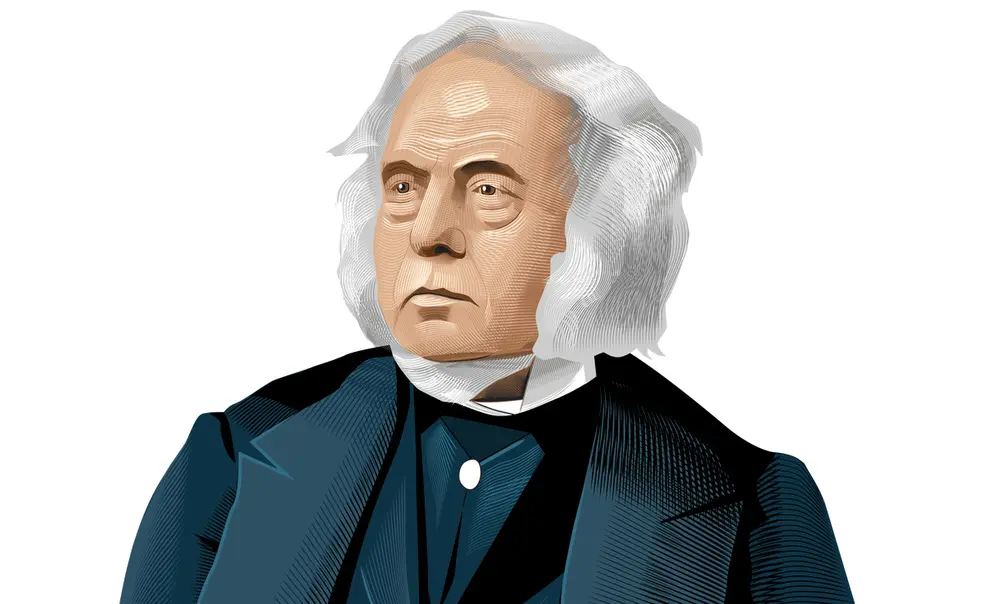

No one stood more firmly in the path of those plans in Parliament than Bright, the member for Birmingham. Born in 1811 to a Quaker cotton mill owner, Bright’s Quakerism made much more of a difference as he matured than his family’s involvement in the cotton business. Bright was drawn into politics by his longtime friend and ally, Richard Cobden, of Manchester, and won a seat in Parliament in 1843. (He would serve in Parliament, with only one brief interruption, until his death in 1889).

An egalitarian to his Quaker core, Bright shook his head in dismay over the British class system. “What a country we live in,” exclaimed Bright, “where accident of birth is supreme over almost every description and degree of merit.”

The great contrast in his view was with the United States: “Everywhere there,” said Bright about the United States, “is an open career; there is no privileged class; there is complete education extended to all; and every man feels that he is not born to be in penury and in suffering, but that there is no point in the social ladder to which he may not fairly hope to raise himself by his honest efforts.”

On those terms, he had no interest in protecting an economic system built on slavery, or in seeing Britain throw its influence behind the Confederacy. If anything, Bright maintained that the South’s attempt at secession had unwittingly placed both secession and slavery in the path of destruction, and Bright did not want Britain to do anything that might prevent that.

“I believe that in the Providence of the Supreme, the slaveholder” has been “permitted to commit ... the act of suicide upon himself,” Bright said in 1864. “He must be deaf and blind, and worse than deaf and blind, who does not perceive that through the instrumentality of this strife, that most odious and most indescribable offence against man and against heaven, the slavery of the South — the bondage of our fellow-creatures, is coming to a certain and rapid end. And Britain must not in the remotest manner, by a word or breath, or the raising of a finger, or the setting of a type, do one single thing to promote the atrocious object of the leaders of this accursed insurrection.”

No wonder Bright and Cobden were known in Parliament as “the Members for the United States.” And no wonder Lincoln’s diplomatic envoy to France, William Dayton 1825, believed that “our only real friends are men like John Bright ... who believe that we are fighting for freedom as well as for our national union.”

Lincoln particularly noticed Bright’s championing of the Northern cause. Rep. William Kelley of Pennsylvania remembered Lincoln greeting a visiting delegation of “English friends” with “an inquiry as to the health of John Bright, whom he said he regarded as the friend of our country, and of freedom everywhere.” Lincoln kept a picture of Bright in his White House office, and in April 1863, he had Charles Sumner, the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, forward to Bright a series of resolutions Lincoln hoped Bright would promote in Parliament, refusing diplomatic recognition to any “new nation” formed anywhere “upon the basis of, and with the primary, and fundamental object to maintain, enlarge, and perpetuate human slavery.”

Bright was, almost literally, on Lincoln’s mind right up to his death. Lincoln had a newspaper clipping of an endorsement speech, given by Bright in 1864, in his pocket the night of his assassination. And in 1871, Bright inherited Lincoln’s gold-headed walking stick from its first recipient, Rev. James Smith, a Scots Presbyterian who had pastored the Lincoln family’s church in Illinois and who served the Lincoln administration in his retirement. “I may mention,” wrote the executor of Smith’s will to Bright, “that the late president’s family are much pleased at Dr. Smith’s bequeathing it to you as it was the president’s wish that you eventually should get it.”

In the process, Bright never lost his interest in American affairs, and in March 1882, even composed an introduction to a British edition of the autobiography of Frederick Douglass. He applauded Douglass for demonstrating “what may be done, and has been done, by a man born under the most adverse circumstances — done, not for himself alone, but for his race, and for his country.” But, Bright added, the Civil War also had a lesson, for the war had shown “how a great nation, persisting in a great crime, cannot escape the penalty inseparable from crime.”

The Bright Pulpit is one of the more easily missed points of Princeton’s architecture. It shouldn’t be. It memorializes one of the closest and most sincere friends of freedom and liberty that Lincoln and the Union had.

1 Response

Franklin Kemp ’62

2 Months AgoPossible Roots for Bright’s Stance

This is an interesting footnote to Princeton’s Chapel and John Bright’s anti-slavery stance, which may have something to do with Britain’s anti-slavery movement and John Newton’s “Amazing Grace.”