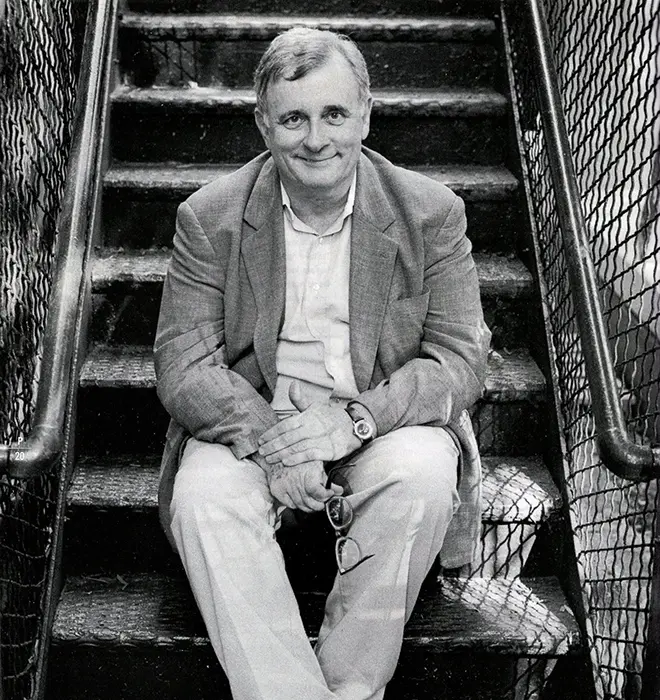

How Edmund White Entered My Life at the Right Time, Several Times

Before he met White, Benjamin Bernard *22 knew him as the writer and Princeton professor who ‘brought gay experience out of the closet and into literature’

The writer Edmund White and I once had a mostly harmless miscommunication with some French diplomats.

In December 2016, when I was a Princeton graduate student in history, White mentioned that he would participate in a panel in New York at the French cultural outpost Albertine. I decided to attend.

I arrived at the venue early but brought White’s new novel to read while I waited.

Just as I reached the stairs to the entrance, a yellow taxi sped to the curb. The door opened and a cane poked out, followed slowly by a leg and then the hefty body of an elderly man: Edmund White. He struggled to lift himself. So, I offered him my arm as we heaved up each step, over the threshold and, finally, into the vestibule.

At that moment, the French diplomatic corps sprang into action. The staff had all been awaiting his arrival. The event manager, lissome and glamorous, stepped forward, cooing: “We are so honored to have you and your friend [she gestured to me] here tonight, Monsieur White.” She assumed we had come together.

I looked quizzically at White, who didn’t miss a beat: “I’m delighted to be here. And this is Ben,” he replied, leaving opaque whether I was his date, friend, or student.

All evening, staff approached me: “Do you need anything, Ben?” “Is there anything we can do for you and Edmund?” Well, of course I went along with it. As for White, my roguish partner in crime seemed delighted to have a young graduate student on his arm — especially in the service of our shared prank.

White died June 3 at age 85. I read that he wrote over 30 books. He brought gay experience out of the closet and into literature. Like many, I knew of him longer than I knew him.

As a closeted suburban teenager in the early 2000s, I first came across White’s byline in the updated edition of The Joy of Gay Sex, furtively spied in the “Gay/Lesbian” section at the Barnes & Noble bookstore. The book offered an affirming account of what had been frightful, taboo subjects for me: gay sex and community. I never imagined that decades later our paths might, briefly, intersect.

The first time I met White was at Princeton, where he taught creative writing. A mutual friend at a book signing offered to introduce me. White smiled, signed my copy of Our Young Man, and wrote his email address on a slip of paper.

When I showed up at his office in November 2016, I took him to task for repeating the debunked canard that Napoleon’s gay consul, Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, in drafting the 1804 Civil Code, was responsible for decriminalizing homosexuality. (Sodomy had already been decriminalized since the 1791 Penal Code.) Well, now I had his attention. We swapped notes on Astolphe de Custine, the gay French marquis beaten by soldiers he was probably cruising in the early 1800s. I had traced Custine’s father’s arrest report in police records from the Terror. As we spoke, a multigenerational psychohistory of sexuality and revolutionary violence unfolded. Now we were cooking.

Years earlier, my undergraduate adviser had recommended I read White’s The Flâneur while studying abroad in France. The book offered a literary framing for my student gallivanting. The Paris he portrayed was that of the modern dandy, strolling and casting judgment all around, in the service of appreciating the historic roots of the very practices of observation in which he engaged.

Soon I left for Paris again, this time for two years of dissertation research. Through a friend, a French playwright housed me for a few weeks. This writer, it turned out, had known White and appeared in his Paris memoirs — but in an unflattering light. I cracked open Inside a Pearl and found the passage: He was “always charming if a bit too world-weary, too exhaustively social.” Nothing about his plays — a damning omission. I had pursued White’s approval, but a new fear swelled in my stomach: of one day becoming another victim of his barbed wit. Still, I felt like I was living the sequel to his memoirs, learning what became of his characters.

Back in America in fall 2019, I made an appointment with White for lunch on Halloween. I nervously rang the doorbell at his Chelsea apartment. His excitement and curiosity set me at ease. He sauteed chicken breasts in cream sauce and described his newest project, which would become A Saint From Texas: a novel about twin sisters, one of whom marries a French aristocrat while the other becomes a poor Latin American nun. Astonished, I replied that my own twin brother, a wealthy lawyer, lived partly in Latin America while I endured scholarly penury in France. Through twinship, White’s novel recognized how Americans use other cultures as mirrors for our values, identities, and fates. He still had it, that novelist’s power to express truth in fiction.

After lunch, when Ed made a gentle pass at me, I was more taken aback than one of his readers had any right to be. What else should one expect from the elder master of the prose and practice of gay longing? By then, his pen had conquered the shame of desire, his or anyone else’s.

That was the last time we met. COVID lockdowns hit. I defended my dissertation and moved to the University of Virginia. He never saw my latest draft project, which I hoped he would appreciate once it was ready for feedback.

Last summer, again in Paris, I recalled The Flâneur when an acquaintance invited me to the Gustave Moreau museum, where he had secured an internship. In the book, the titular ambling dandy relates how Moreau, a 19th-century Symbolist, inherited his family’s townhouse and transformed it into a peculiar gallery for his own paintings. White criticizes Moreau: for his style (“camp without the humor”), his unfinished paintings, his ill-conceived ego-monument. “Moreau’s museum,” White wrote, “quickly became such a quiet backwater that it was an ideal place for a lovers’ rendezvous.” That line perfectly captures the decadent ethos: eros flourishes in an abandoned ruin.

The day of our date, the museum was packed — too crowded for a “lovers’ rendezvous” — but it was as delightfully eccentric as promised. Thinking of The Flâneur’s detours into Huysmans and Wilde — authors I now teach — I understood that it might be precisely because of Moreau’s failings, not despite them, that White crowns it his favorite public museum.

I now view White’s description of our French playwright friend differently, too. From a student of those latter-day melancholic epicureans of the fin de siècle, the judgment “always charming but a bit too world-weary” might well be the highest compliment.

These passages provide a window onto White. Witness to the Stonewall riots in 1969 and to aristocratic dinner parties; unapologetically erotic, as impish a gossip as he was studied and highbrow: this éminence sleaze served as a transatlantic apostle of libertinism for the age of gay liberation.

And for the AIDS era, too. That disease long since felled his cohort of distinguished gay artists and writers, whereas White defied HIV to write and teach for decades more. His fruitful career shows what might have happened had the Michel Foucaults and Keith Harings lived longer. The meager supply of gay elders surviving from his generation could never meet the demand for mentorship of two generations of father-hungry queer writers. But I think White took pleasure in conjuring the magic of letters for those of us lucky enough to cross his path — or arrive at the venue at just the right moment.

Benjamin Bernard *22 is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Virginia.

1 Response

Leo Racicot

2 Months AgoFortunate to Call Him a Friend

I, too, when out with Ed. On one of our “dates” I would be amused by the responses the public would have when seeing us out together. Ed and I would both play it up to the hilt and derived devilish amusement from seeing people’s reactions. Of course, a night out is a night out, an afternoon at the theater is an afternoon at the theater, a frolic at the ballet is a frolic. Who’s to say what constitutes a date when you’re on the town with the famous Edmund White, who was as recognizable in and around Manhattan as was/is Fran Lebowitz. My, but weren’t we lucky to call him “friend,” even for a brief time.