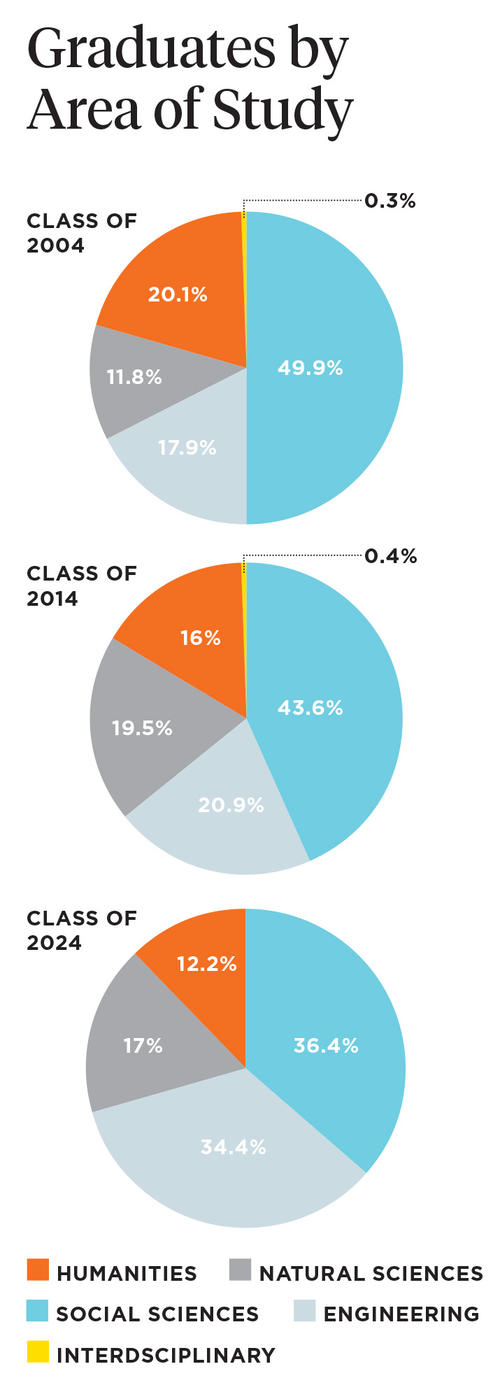

Humanities Are Alive and Well at Princeton. So Where Are the Humanities Majors?

In Princeton’s Class of 2024, just 12.2% of graduates majored in humanities departments

On April 11, members of the Class of 2027 flocked to Cannon Green in the rain to celebrate “Declaration Day.” While students lined up to take pictures behind the black-and-orange ECON (economics) and COS (computer science) banners — where 164 and 165 sophomores, respectively, declared a major — the SLAV LANG & LIT banner stood lonely. In fact, no sophomores chose to major in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures this year.

At Princeton, fewer students are majoring in the humanities, mirroring nationwide trends. An oft-cited American Academy of Arts and Sciences study found that the number of humanities majors nationally dropped by a third between 2012 and 2022. While many humanities departments at Princeton, including English and classics, have experienced consistent interest, some are in a more precarious position. In the Class of 2017, the French and Italian department, for example, had seven majors; one member of the Class of 2027 declared a major in the department. Near Eastern studies and East Asian studies have seen similar declines. In the Class of 2024, 12.2% of graduates majored in humanities departments, according to the University’s latest Common Data Set.

But the humanities are alive at Princeton. In 2024, the Humanities Initiative was established to sustain the excellence of the humanities while envisioning new models to “invigorate and make even more vital” humanistic study, in the words of Rachael DeLue, an art and archaeology professor and the initiative’s director. Building on the strengths of the Humanities Council, the initiative aims to eventually transform into a Humanities Institute, which will provide funding and other forms of support for humanities research and teaching.

Humanities courses remain popular among students. Hundreds of undergraduates take Chinese and Spanish language classes. Courses such as the Slavic department’s Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky class and the German department’s Learning (and Teaching) New Languages routinely send students to a waitlist to enroll. So why hasn’t this interest translated into more majors?

Many professors attribute this trend to the misperception that majoring in a subject like economics is a professional necessity. Professor Federico Marcon, chair of the Department of East Asian Studies, said that in today’s world, students increasingly believe that it will be difficult to acquire a stable job post-graduation, despite the United States’ relative economic stability. Students’ academic choices sometimes constitute “an emotional response to an irrational misreading of the economic, social situations of the United States,” he said.

Kamila Isaieva, a sophomore from Ukraine, expressed her interest in anthropology and comparative literature but was worried about career prospects in those fields. She chose to major in the School of Public and International Affairs.

“My parents think that if I go into humanities, I would waste my degree in a certain way,” she said.

Princeton professors told PAW that, with very few exceptions, there is no substantive correlation between major and job prospects. Andrew Feldherr, a professor of classics, suggested that the University’s lack of early career advising means that “students have a lot less awareness of what the professional consequences of their intellectual choices are, and they create false dilemmas for themselves as a result.” Feldherr, who is his department’s director of undergraduate studies and a former Mathey College academic adviser, elaborated that “there are very, very few majors that give you a directly employable skill.”

According to statistics from Princeton’s Center for Career Development, humanities majors go on to pursue a range of careers. For example, directly after graduation, 24% of English majors in the classes of 2016 through 2024 went on to business or law, as did 29% of classics majors and 26% of East Asian studies majors.

In a written statement to PAW, the Center for Career Development noted that “major does not dictate career path, and Princeton students pursue a wide array of careers after graduation, regardless of major. A Princeton education provides students with knowledge, skills, and opportunities to enable them to pursue careers they find meaningful in any field.”

Departmental websites feature profiles of alumni who pursued career paths unrelated to their major. The French and Italian department highlights alum Khameer Kidia ’11, a global health physician at Harvard Medical School and the University of Zimbabwe. Former classics major Kevin Moch ’10 is now a software engineer. Slavic major Alan Kashdan ’75 pursued international trade law after graduation.

Princeton’s single-major policy poses additional challenges. Professor Göran Blix, chair of French and Italian, said that this policy is “to the detriment of the humanities departments.” He added that “colleagues at other institutions have pretty healthy enrollments in their majors, largely because they allow double majors so students can pursue a safe major and at the same time major in a field that they’re more passionately attracted to.”

“I really want to do things that I’m passionate about that fulfill me academically. But at the same time, I want to be pragmatic,” said Ariana Loughlin ’27, who is majoring in economics. “I want to set myself up to be able to have as many opportunities as I can. I feel like economics does that.”

Loughlin said that if she wasn’t worried about her career path, “I would just be side-questing all the time,” taking classes in classics and Slavic literature. She plans to pursue minors in both classics and Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian studies.

Similarly, Rohan Sykora ’27 lamented that demanding requirements for his economics major and computer science minor prevent him from pursuing his other interests, like Arabic language. Sykora said that career prospects did not drive him to declare an economics major. He plans to apply the analytical frameworks economics has taught him to thinking about how to create “better, more ethical policy.”

Unique challenges faced by international students are also calling some to question the University’s ban on double majors. Feldherr said that he recently advised two students who would have majored in classics if not for requirements that steered them to STEM subjects. The United States’ Optional Practical Training program requires international students who intend on working in the U.S. after graduation to go into a field related to their area of study.

Several undergraduates majoring in the humanities reflected on the benefits of smaller departments, including a small student-to-faculty ratio.

“Since I’m the only person, they’ve been super attentive to whatever I need, trying to help me with anything. It’s been great,” said Jack Feise ’26, the only current major in the Slavic department.

“We’re kind of like a small family,” said Laura Kalin, an associate professor of linguistics in the Council of the Humanities. “The students know what I’m working on. I know what all of our students are working on.”

Majoring in a small department also provides practical benefits. Professor Ilya Vinitsky, chair of the Slavic department, noted that regional specialists are needed in a plethora of fields — including law, journalism, and the private sector. Moreover, in smaller departments, students have “more contact hours with professors, which can result in better letters of recommendation” in addition to deeper professional experience.

Learning a language like Russian — and having the opportunity to study its literature and culture — is “practical and for the soul at the same time,” Vinistky said.

A Princeton liberal arts degree can give students the toolset to pursue any career. DeLue underscored the importance of the humanities in teaching “information in context, cross-cultural dialogue, and empathy.”

Darena Garraway ’27, who just declared a classics major, said that learning Latin and Greek has strengthened her analytical skills. “The way I think totally changed, structurally, in a way that can help me in a career in consulting,” she said.

While humanities programs are being defunded on the federal level, Princeton has maintained a strong commitment to its humanities departments. Kalin shared that the University has committed to expanding the Program in Linguistics. The classics and Slavic departments have recently hired new faculty.

“Higher education is currently facing a lot of questions. Humanities at Princeton is leading the effort to answer those questions,” said DeLue. “Princeton is meeting the moment.”

No responses yet