International Standouts Make a Big Impact in Ivy League Field Hockey

There are 53 Ivy field hockey players whose listed hometowns are outside the United States

When Princeton field hockey plays host to Harvard Oct. 14 in a matchup of preseason Ivy League favorites, a whopping 24 of the 48 players involved will hail from outside the United States.

The programs, which have split the last six Ivy titles and appeared in four NCAA Final Fours in that span, have taken different paths to building rosters that can compete with the nation’s best. But both paths involve international recruiting, and the rest of the conference has followed.

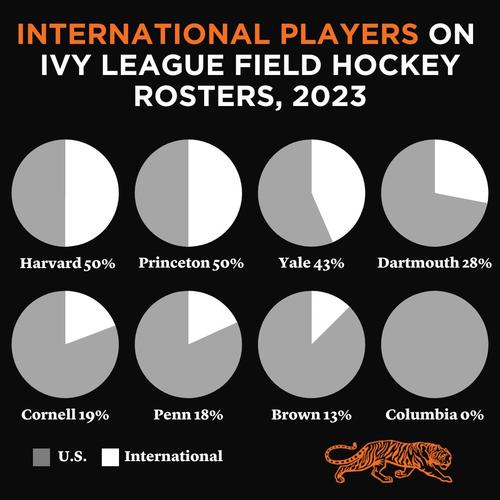

This season, there are 53 Ivy field hockey players whose hometowns, as listed on team rosters, are outside the United States. They comprise 29% of the league’s players, and Harvard (50%), Princeton (50%), and Yale (44%) have even higher international representation. Columbia is the only Ivy team without an international player this season.

Princeton continues to attract elite American players, which historically has helped it dominate the Ivy League (27 championships in 43 seasons). But recruiting top international players as well, head coach Carla Tagliente said, “puts us more on a similar playing field to the Marylands and the UNCs,” two of the nation’s top programs.

Recent examples include Hannah Davey ’23, the reigning Ivy League Defensive Player of the Year from England, and Clara Roth ’21, the 2018 Offensive Player of the Year from Germany. Both players started in Princeton’s 2019 national championship game loss to UNC.

For Harvard, international recruiting has been foundational to its success since head coach Tjerk van Herwaarden’s arrival in 2012. As he built the program, it was sometimes easier to sell Harvard to elite international players than to elite domestic ones.

Dutch midfielder Bente van Vlijmen, who graduated in 2020 as a four-time All-American, was pivotal to Harvard’s rise. She and classmate Maddie Earle, who is from New Zealand, “changed this program from a culture perspective and from a ranking perspective,” van Herwaarden said. “I think that eventually made it easier for us to have other people buy in and now get all the top Americans [to] look at Harvard also.”

“Our [international] players that come in are very much blended into the family of Princeton field hockey. They’ve really added a lot to the game; they’ve added a lot to the culture, not just in our program, but in college hockey altogether.”

— Carla Tagliente, Princeton field hockey head coach

International recruiting has long existed in the Ancient Eight: For example, Canadian Amy MacFarlane ’97 won two Ivy League Player of the Year awards at Princeton in the mid-1990s. But it has increased in popularity over time, coaches say, just as it has throughout Division I. U.S. coaches took notice of how international players could beget team success, and early international players created a blueprint for younger ones.

International recruiting in the Ivy League has particularly accelerated in the past decade, aided by some newer head coaches. Harvard’s van Herwaarden (the Netherlands), Cornell’s Andy Smith (England), and Dartmouth’s Mark Egner (Ireland) are all from outside the U.S., and Smith and Egner were hired in the past four years. Coaches with international playing experience, such as Princeton’s Tagliente (hired in 2016) and Yale’s Melissa Gonzalez (hired in 2022), have also embraced recruiting globally.

“It’s definitely grown significantly during my 14 years,” said Penn’s Colleen Fink, the league’s longest-tenured head coach. “Right now, we’re probably at an all-time high.”

Coaches often recruit international players through showcase events, which are tournaments or practices held in the players’ home countries and hosted by companies that connect international talent with U.S. college coaches. Club and high school play also provides exposure. England has been a recruiting hotbed, as many elite players there are interested in NCAA field hockey. That includes national-team-level talent in a country that was sixth in the International Hockey Federation’s world rankings as of Sept. 1, 10 spots above the U.S. In countries such as the Netherlands and Germany, which boast top-five teams, the top players often stay home to train with their national team.

Ivy programs seeking to challenge Princeton and Harvard have embraced international recruiting, too. Four of Yale’s six freshmen this season are international, including three from England. Penn has two international captains, Lis Zandbergen and Allison Kuzyk, for the first time in Fink’s tenure.

“If Harvard and Princeton are prioritizing it,” Fink said, “then I think yes, everybody else needs to be taking a very close look at it.”

International recruiting has paid dividends leaguewide, even for programs that haven’t challenged for titles. Since 2017, 23 international players have made at least one All-Ivy first or second team, including at least one player from every program. Seven have won Player or Rookie of the Year, including Davey, Roth, van Vlijmen, and the reigning Rookie of the Year, Harvard’s Bronte-May Brough. International players comprise one-third of the All-Ivy selections and nearly half of the major award winners in that span, and English players have been particularly well represented.

International players have also had a broader impact, adding diversity to a sport that is relatively homogeneous in the U.S. and bringing styles of play and cultural influences from around the world. The result is a richer and more competitive field hockey experience in the Ivy League.

“Our [international] players that come in are very much blended into the family of Princeton field hockey,” Tagliente said. “They’ve really added a lot to the game; they’ve added a lot to the culture, not just in our program, but in college hockey altogether.”

1 Response

Mirna Goldberger ’88

2 Years AgoInternational Students and Field Hockey in the ’80s

In reading your article on the impact of international athletes on the game of field hockey (Sports, October issue), I wanted to add that the tradition at Princeton of recruiting foreign players started before the time frame mentioned in the story. I think that I was the first foreign recruit in 1984.

I clearly recall meeting coach Betty Logan way back in 1983, as I was initiating my life in the U.S. as a newcomer from Argentina. It was a brief encounter at the tournament she used to run in Port Jervis, New York.

Little did I know that a year later, I would be enrolling at Princeton and starting in the first game of the 1984 season. I had developed as a player at the Northlands School in Argentina, where my team had won the national championships a couple of years in a row. My stickwork was European style, where the hypotenuse ruled whenever you could find the gap, and transitioning to playing on a U.S. field of the ’80s with all the “flat and through set plays” was horrifyingly predictable and hard to adjust to. I am glad the art of field hockey at Princeton is now a gratifying sight.

Princeton had its worst record during my time as a field hockey player there, but I do not regret it one bit — it was the opportunity of my life being able to attend the “best place of all.” I will always cherish my experience as a college athlete.