In Memoriam

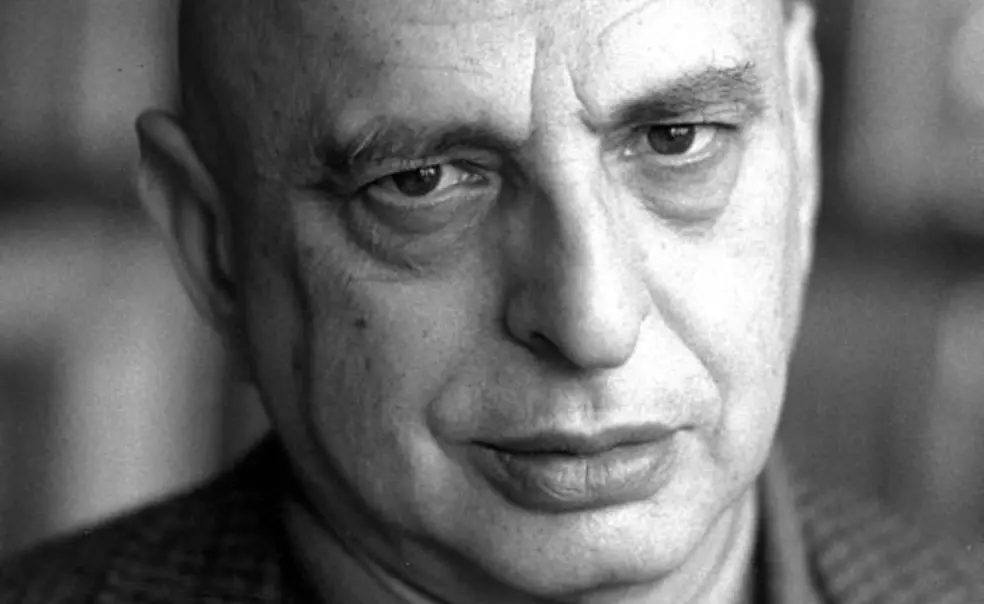

MARVIN BRESSLER, a popular teacher and adviser in the sociology department who left his mark on the University’s curricular and extracurricular offerings, died July 7 in Skillman, N.J. He was 87. A faculty member from 1963 to 1993, Bressler chaired the Commission on the Future of the College, which in 1973 produced a review of educational and social opportunities for undergraduates. The report envisioned “a place where students can learn from one another,” and made recommendations that included enhancing interdisciplinary studies and expanding new facilities like the Third World Center (now the Fields Center for Equality and Cultural Understanding).

Bressler also chaired the sociology department for 20 years. As a scholar, he devoted much of his research and writing to higher education and also studied health care, cultural pluralism, and the moral implications of sociobiology. A close friend of basketball coach Pete Carril, Bressler served as a mentor for generations of Princeton men’s basketball players and inspired the Academic-Athletic Fellows Program, which connects faculty and staff with varsity sports teams. Three Princeton classes — 1968, 1971, and 1982 — named Bressler an honorary classmate.

[A memorial service for Bressler will be held Oct. 10 at 3 p.m. at Robertson Hall's Dodds Auditorium. A reception will follow from 5 to 7 p.m. at Prospect House.]

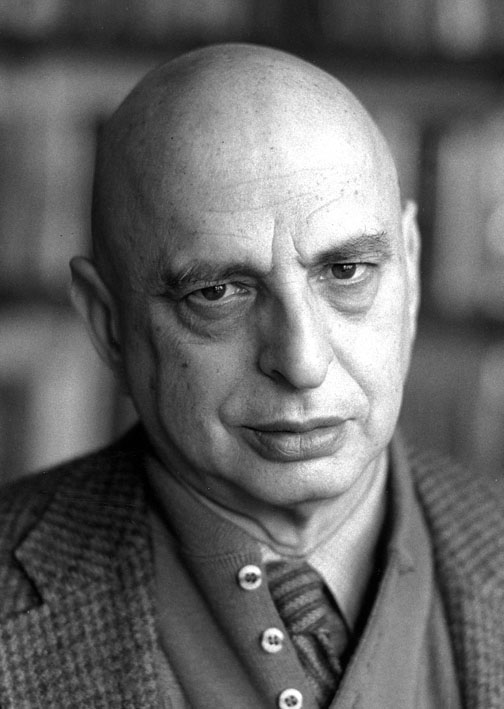

NORMAN RYDER *51, a sociologist and demographer best known for his studies of fertility in the United States, died June 30 in Princeton at age 86. As a Princeton graduate student, he established the “cohort” approach, studying a group of people born in the same period of time who go through life together.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Ryder and Princeton sociologist Charles Westoff co-founded and co-directed the influential National Fertility Studies. Through thousands of interviews, the studies documented attitudes and behavior toward childbearing and contraception. Ryder and Westoff later assisted in the development of the World Fertility Survey. Ryder taught at the University of Wisconsin for 15 years before joining the Princeton faculty in 1971. He retired in 1989.

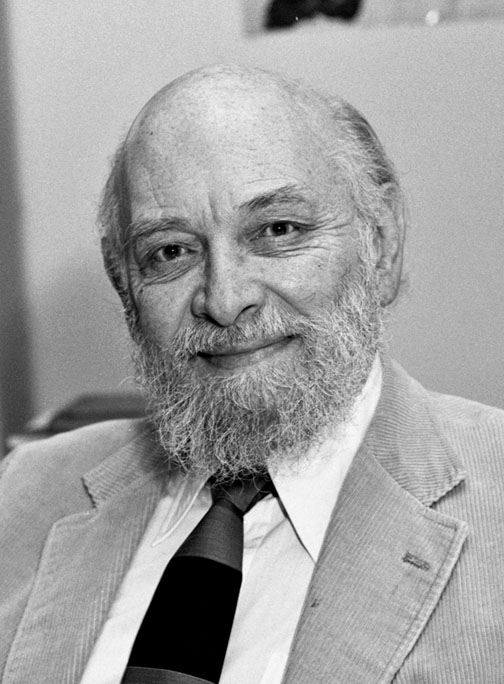

ROBERT C. TUCKER, a professor of politics and international affairs who wrote two widely read biographies of Joseph Stalin, died in Princeton July 29. He was 92. Tucker gained his expertise on the Soviet Union firsthand, traveling to Moscow in 1944 for what would be a nine-year stay at the U.S. embassy. He entered academia soon after his return to the United States.

Tucker served on the Princeton faculty from 1962 to 1984, founding the Program in Russian Studies. He wrote extensively about Marx before beginning his work on Stalin. Cold War diplomat George F. Kennan ’22 called Tucker “one of the great students of Stalin and Stalinism,” according to The New York Times.

3 Responses

Christine Moses-Egan ’84

10 Years Ago'A passion for intellectual pursuit'

Professor Marvin Bressler was one of the most compassionate people I have ever met. He knew how to get the best out of his students. I will always be grateful for his passion for intellectual pursuit and his ability to inspire me to think critically about the world. I truly appreciated his sense of humor, his dedication to his students, and his intellectual rigor. He was an amazing man.

M.J. Andersen ’77

10 Years AgoTalking with Bressler

I was inexpressibly saddened to read about the passing of Marvin Bressler (Notebook, Sept. 22). Somehow, this prominent professor always managed to find time for a scared girl from the sticks. He was kind, brilliant, thoughtful, on to himself (“excuse the pomposity”), and extremely funny.

Shortly before I graduated, a friend and I stopped by his office to say goodbye. We ended up in another of the long, rambling conversations I had grown to treasure. Finally, he opened a file drawer and pulled out a glossy photo of a handsome, curly-haired youth –– himself, as it turned out. Without a trace of regret, he noted: “I was a scourge.” That he was.

Richard Ostrow ’71

10 Years AgoFaculty remembrance: Marvin Bressler

Professor Marvin Bressler (In memoriam, Sept. 22) was a great teacher and an even better friend. For me, he personified liberal academia. But for his wise counsel, I would not have made it through the turbulence of the late ’60s. Our frequent meetings through the years, when he was either on an admission tour or accompanying the men’s basketball team in his role of “academic adviser,” never failed to help clarify issues in my adult life. If there were ever a better conversationalist, I never met him.

As the biographer Liva Baker quoted a disciple of Justice Oliver Wendall Holmes: “[He] talked a great deal, as the natural center of the company in which he found himself ... There was an almost impish charm to the fluency with which he would catch a subject, toss it into the air, make it dance and play a hundred tricks, and bring it to solid earth again. There was ... a sense of enjoyment even in the serious treatment of a serious subject. ... As he talked, he drew inspiration from his company; he challenged and desired response, contradiction, and development. He liked to have the ball caught and tossed back to him, so that he could send it spinning away again with a fresh twist. Talk was a means of clarifying ideas, of moving towards the truth, but it was a great game, too.”

Holmes once admitted that if he lost both arms and both legs and had to be carried every day into the marketplace and allowed to talk, he would have all that he wanted out of life. Add a pipe and an audience, and the same could be said of Marvin Bressler.

[node:field-image-collection:0:render]