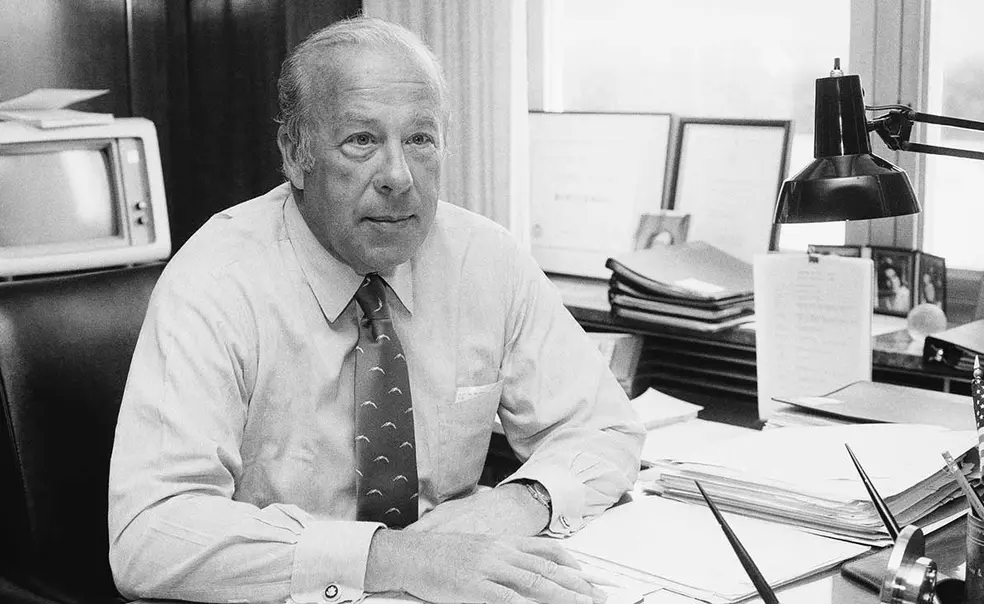

A Personal Tribute To a Public Man: George Shultz ’42

Editor’s note: George P. Shultz ’42, a titan of diplomacy, died Feb. 6.

George Shultz ’42 was the consummate public servant. When he died, The New York Times devoted two full pages to an account of his career. As every article has mentioned, he held four Cabinet offices over a 20-year span from 1969 to 1989: director of the Office of Management and Budget, secretary of labor, secretary of the treasury, and secretary of state. The only other person in history to hold four Cabinet positions was Elliot Richardson, who earned his place in history during the Watergate scandal by resigning rather than firing special prosecutor Archibald Cox at Nixon’s direction. Distinguished company indeed.

Shultz’s devotion to Princeton was legendary. I remember vividly his returning for one of his later reunions in a very proper blue blazer that he would open with delight to flash a bright orange lining. Rumors also abounded about a certain tiger tattoo he supposedly acquired to demonstrate his enduring love for his alma mater. Once when I was at his house in California, I saw a stuffed tiger that a friend had sent him with a tiny picture of Shultz affixed to its posterior.

In this brief tribute, however, I wish to remember a different George Shultz — if not exactly the private man, then at least the man who took the time to reach out to the new dean of the School of Public and International Affairs. He himself had been dean of the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business for five years in the 1960s.

On one of my early trips to California as dean, George invited me to lunch in Palo Alto. We ate outside on a glorious day. George had assembled a remarkable group of scholar-administrators. I recall how firmly but deftly George directed the conversation, raising questions about how to encourage interdisciplinary work, how to marry academic scholarship with policy expertise, and how to navigate the competing pressures of students, faculty, staff, alumni, and university leadership.

Throughout it all, his wife, Charlotte, was the perfect hostess. She served for many years as chief of protocol for the state of California and then for the city and county of San Francisco. For dessert she brought out a cake with the cover of my first book, which had just come out, miraculously rendered in icing. I’ve never forgotten the touch.

In retrospect, I should not have been surprised at the care and attention both Shultzes paid to relationships. In 2004, I co-taught a Princeton freshman seminar called “So You Want to Be Secretary of State?” (It may not surprise you that it was oversubscribed!) George — Secretary Shultz for those purposes — came to speak to the class, an extraordinary experience for all of us.

George also took on big challenges ... . He used his century on this Earth to make as much of a difference as possible.

What I remember most from his remarks and responses to questions was his metaphor of “gardening” for the conduct of foreign affairs. His point was that national interactions, like personal ones, are relationships that need to be carefully tended. Watering and weeding are particularly important, he noted: ensuring that you pay enough attention to keep them flourishing and to observe and remove any problems that might arise early on.

I have heard other leaders and entrepreneurs describe leading as gardening, in the sense of growing talent, but the Shultz view was far broader. I can just imagine him sitting in the grandeur of his office and reception room on the seventh floor of the State Department, surveying the world and tending U.S. alliances, friendships, and even rivalries with care.

Perhaps the most important exchange I had with George was when he gave me advice I didn’t follow. In November 2008, just after Barack Obama was elected president, I wanted to serve in his administration. I had wanted to go into government since I was an undergraduate, but my party’s fortunes and my own had never aligned. I called George for advice. When I mentioned that I was interested in the Office of Policy Planning (an internal State Department think tank founded by George Kennan ’25), George demurred. Take a line job, he said, one with direct responsibility for results. Academics always want advisory positions, he elaborated, but you should get into the fray.

I did end up as director of policy planning, but I now give George’s advice to many of my mentees who are seeking positions in government. He was no slouch as a professor, holding positions at MIT, the University of Chicago, and Stanford, but he was an academic who loved action, a relatively rare breed.

George also took on big challenges: managing U.S.-Soviet relations, promoting democracy, reducing the threat of nuclear war, and toward the end of his life, combatting climate change. He used his century on this Earth to make as much of a difference as possible.

George Shultz’s life embodied Princeton’s motto: In the nation’s service and the service of humanity. Still, behind his grand public persona, he was a lovely, slightly gruff, no-nonsense, witty, devoted, and caring man.

3 Responses

George Dies ’73

4 Years AgoHumorous Encounter with Shultz

Re: Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80’s remembrance of George Shultz ’42, I had a memorable encounter with him in Paris during his stint as Secretary of State in the mid-1980s. Prior to his giving a speech at a Stanford Business School alumni event, I managed to get a former Foreign Service colleague to introduce me. I reminded him that a portion of my class walked out when he was awarded an honorary degree at my graduation in June 1973 (in protest of the Vietnam War). Secretary Shultz smiled and replied, “Oh, that was a pretty minor protest — I have been the target of much bigger ones since then.”

The same former colleague told me about the plush tiger with a small portrait affixed to its posterior, mentioned by Dean Slaughter. It apparently was left on the Secretary's airplane seat by one of the press corps during a trip abroad. Secretary Shultz lifted it up, turned it around, and promptly moved the picture from one side of the posterior to the other, saying to his staff assistant, “Tell them to do their homework next time.”

Sara Judge ’82

4 Years AgoA Chance Encounter in China

The tribute to George Shultz ’42 by Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 (Princetonians, April issue) brought back memories of my conversation with Secretary Shultz in 1984. Learning of President Reagan’s plans to visit China, I wrote a letter to request a meeting. With the incredible gumption of a 24-year-old who had traveled halfway around the world to live and work in Beijing, I thought it would be interesting for Reagan to hear about China through the eyes of a young American. To my surprise, I received word that the president would like to meet.

On the day of Reagan’s reception with the U.S. business community, I was ushered into a room next to the ballroom at Beijing’s Great Wall Hotel. Perched on the edge of a table was Shultz, also waiting for Reagan to arrive. Although shy by nature, I realized that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Princeton was the conversation opener, of course. When he learned I’d been living in Beijing for two years, he asked all of the questions I had prepared to speak about with the president: impressions of the people I interacted with, the lingering impact of the Cultural Revolution, the slow opening of markets and loosening of economic restrictions, the progress of American companies seeking to gain a foothold in China, the social campaigns attempting to influence behavior and thought, the restrictions on my movement and travel. He was authentically curious and kind. And, yes, I did find myself wondering about whether the story of the tiger tattoo was true.

Kim Howie *78

4 Years AgoNaming Opportunity

I recently spoke with a junior who said she was in the “formerly Woodrow Wilson” program. I assumed it was because it was so much easier to say than the School of Public and International Affairs. Princeton needs to find a easier-to-say and more distinguished name for the School. The last paragraph of Anne Marie Slaughter’s article succinctly makes the case for naming the School after George Shultz; both as a statesman and personally.