Perspective

Richard Just is the editor of The New Republic and a member of PAW’s advisory board.

In August, three of my closest friends and I did something that we have done every summer for the past 10 years. We took time off from our jobs and moved into dorms on Princeton’s campus. With us were about 40 other people: the students and counselors of a summer program that we founded in 2002, and have run every year since.

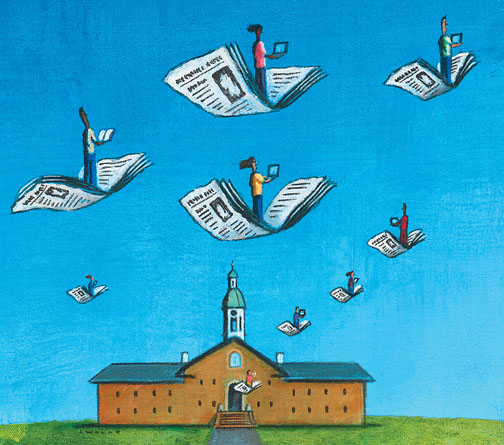

The four of us — Michael Koike ’01, Gregory Mancini ’01, Rich Tucker ’01, and I — had no clue what we were getting into back in 2001. We did have what we thought was a good idea. All of us had been editors at the Prince, which, like most newspapers at elite colleges, was not a very socioeconomically diverse place. During the second half of our senior year, we hatched an idea: What if we founded an all-expenses-paid program that gave high school students from underprivileged backgrounds a crash course in journalism? We could bring them to Princeton, ask professional journalists to teach classes, work with the students to put out a newspaper, and help guide their college-application process during the fall of their senior year. Some of them, we hoped, eventually would end up as writers and editors at the Prince.

It all seemed very straightforward, and, at first, it was. We got seed money from both President Harold Shapiro *64 and Hodding Carter ’57, who at the time ran the Knight Foundation. In the fall of 2001, we bombarded urban high schools with information about our Summer Journalism Program (SJP), and received 33 applications. We recruited friends from Princeton to serve as counselors. In the end, 21 students and about as many counselors attended the program. None of us knew anything about teaching that first year, and, looking back, we probably weren’t very good at it. But at least we were enthusiastic, and the students seemed to get a lot out of the experience.

In succeeding years, a few things happened. First, we realized how little we had understood about the disadvantages low-income students face in the college process. We figured that helping the best students from the worst urban high schools get into Ivy League colleges would be mostly a matter of encouraging them to apply, but we found out it wasn’t that easy. Our students didn’t have the support systems that help wealthier students get into elite colleges — namely, parents who know the college-application system inside-out and savvy, helpful guidance counselors. That first year, not long after the program ended, one of our best students called me in tears because her guidance counselor had told her dismissively that students from her high school should not bother applying to schools like Princeton and Georgetown.

We realized that it wasn’t enough simply to bring a group of students to Princeton for 10 days. If we wanted to make a difference in their lives, we would have to become more involved in their college applications — the way a high-priced private admissions consultant might for wealthy students. Each of us worked with five or six students on their applications. We helped them figure out which SAT subject tests to take and which schools to apply to. We helped with their financial-aid applications. And we worked with them on their essays. This part of the process usually started with a phone call in late August or early September to brainstorm ideas. Once we agreed on a subject, the student would write a draft, and then the back-and-forth of editing would begin, with each student going through four, five, six drafts. Our students’ life stories frequently were both painful and inspiring. They had lived in homeless shelters, emigrated from impoverished countries, and generally grown up with a level of deprivation and difficulty that no child should have to face. And yet, somehow, they had emerged as ambitious, optimistic, kind people. Helping them figure out how to craft these stories into narratives was tremendously rewarding, since the results frequently were not just strong college essays but genuinely moving pieces of writing.

Slowly we started to get results. In our fourth year, a student got into Princeton. By year six, more than half of our students were going to Ivy League or equally selective schools. Many of these students ended up at their college newspapers, but many didn’t, and that was OK with us. Leveling a college-admissions system that was profoundly unfair for the smartest students from the worst high schools had become a goal unto itself.

In 2006, we became part of the University, but we continued to run the program ourselves. Despite a strict combined parental income limit of $45,000, we were receiving more and more applications. By 2007, we were getting hundreds of applications each year for 20 spots. Between reading applications, interviewing the 50 or so finalists, hiring interns (generously funded by the Class of 1969) to help us run the program, recruiting counselors, editing our students’ college essays, and putting together the schedule each year, the program was becoming something close to a second full-time job. The toughest part has been fundraising: Since our original grants ran out, we have had to cobble together from donors the $50,000 needed to run SJP each year. We dreamt of finding someone who might endow the program and give us some financial stability, but we’re still searching.

As the years went on, we accumulated some pretty great statistics: dozens of alumni currently at Ivy League schools and students who have gone on to land internships or jobs at many of the top news organization in the country, from The New York Times to The Associated Press to NPR to NBC. And our original goal of diversifying college newsrooms worked out, too. In the past few years, some of the top editors and writers for the Prince, The Harvard Crimson, The Yale Daily News, and The Columbia Spectator have been SJP alums.

We also managed to create a community of students who didn’t just achieve remarkable things, but who supported those who were a few years behind them. Our volunteer counseling staff this summer consisted largely of SJP alumni from 2005 through 2009, many of whom have been returning regularly to the program. Last year, when our students who had been admitted to Harvard traveled to Cambridge to visit the university, they were met at the train station by a program alum who was a Harvard sophomore. She had taken it upon herself to make sure they found their way to campus because they were all part of the SJP family.

This summer, our 10th, was as amazing as any other. As in past summers, our friends from Princeton and from the journalism world — reporters and editors from The New York Times, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Politico, and CNN — served as volunteer counselors or taught classes.

None of us knew what we were getting into 10 years ago, but looking back, we’re all glad that we gave this idea a shot. The biggest reason, of course, is that we got to make a difference in the lives of some amazing kids. But the journalism program has been a learning experience for each of us as well. All four of us grew up in relatively privileged backgrounds. We had parents who expected us to achieve and helped us along the way. We went to high schools where applying to colleges like Princeton was the norm. I don’t think any of us really understood 10 years ago just how much perseverance it takes to succeed when life has put so many deeply unfair disadvantages in your way. We thank our students for teaching us that.

No responses yet