The President’s Bookshelf: Two Selections for This Fall

As the fall semester began, a Princeton junior emailed asking whether I might recommend books to him. His message reminded me of how special Princeton students are; some people worry that young people no longer read books, but this Tiger wanted suggestions to supplement his already heavy classroom assignments.

Princeton alumni also ask me for book recommendations occasionally, so I thought that I would pass along the two that I offered to our student. Both books make valuable arguments not only about the specific topics they address, but also about the mission of research universities and a liberal arts education.

In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us, Stephen Macedo *87 and Frances Lee (Princeton University Press, 2025)

In Covid’s Wake, coauthored by two Princeton politics professors, is a scathing critique of America’s response to the pandemic. Macedo and Lee demonstrate how groupthink—and sometimes outright censorship—led policymakers and academics to make bad choices with lasting costs to the country.

In Covid’s Wake is essential reading for many reasons, including the light it sheds on arguments about the conditions required for robust, truth-seeking scholarship and debate at universities. Too often, people who talk about “viewpoint diversity” in higher education assume that it means having a balance of liberals and conservatives, or that it requires universities to mirror disagreements from the political realm.

That is the wrong way to think about scholarship. Macedo and Lee, who describe themselves as “liberal democrats,” have harsh words for “the Blue-state policy orthodoxy” about masking, school closures, and other nonpharmaceutical interventions.1 Their argument defies categorization as “progressive” or “conservative”: they are skeptical about masks but bullish about vaccines, for example.2

Macedo and Lee warn us against “the premature moralization of disagreements,” and they insist on “the willingness to entertain doubts, listen to other points of view, and revise our own commitments.”3 That—not some sort of statistical liberal/conservative balance—is exactly what “viewpoint diversity” ought to mean in the context of a great research university.

I am persuaded by much of In Covid’s Wake but disagree with aspects of it. You might too. Good: thoughtful—and evidence-based—argument about what worked during the pandemic, and what did not, is exactly what America needs. We need to identify our mistakes now and correct them, before another virus engulfs the globe.

George Will *68 wrote in The Washington Post that In Covid’s Wake represents “social science at its finest.” 4 I concur enthusiastically.

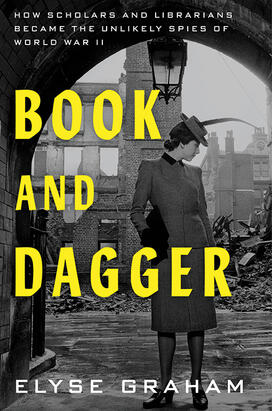

Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II, Elyse Graham ’07 (Ecco, 2024)

PAW’s loyal readers may recognize Elyse Graham as the author of lyrical, illuminating essays about Princeton’s history that appear regularly in these pages. Her recent book tells an amazing story: how humanists from America’s research universities rebuilt the nation’s espionage operations and helped win World War II.

Book and Dagger introduces some fascinating characters, like Joseph Curtiss, a young Yale English professor who becomes agent 005 (I’m not kidding) based in Istanbul for the Office of Strategic Services.5

More generally, it describes how modern intelligence operations draw on core humanistic skills: the abilities required to translate, interpret, and find meaning in reams of text drawn from newspapers, dispatches, and other messages. No wonder the American and British governments recruited agents from universities and libraries.

While reading Graham’s book, I could not help but recall that when General Mark Milley ’80 visited Princeton during his service as Chair of the Joint Chiefs, he met with Professor Ekaterina Pravilova, a specialist on the Russian Empire and early Soviet history, so that he could learn more about how Russians viewed their history.

I remembered, too, that General Christopher Cavoli ’87, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (and, like Milley, is a recipient of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson Award) has a graduate degree in Russian and East European Studies and speaks four languages: English, French, Italian, and Russian.

As Graham notes, American lore, including movies like Oppenheimer, gives bomb-making scientists credit for winning World War II. She argues persuasively that humanists deserve far more credit than they get.

Book and Dagger is also a potent antidote to noxious claims that describe universities or professors as hostile to our country. The vast majority of the students and professors I meet on the Princeton campus love America and want to make it the best it can be. As Graham reminds us, we need their talents, not only in the STEM disciplines but also in the humanities, to build the future that our children deserve.

I’ll conclude (self-indulgently!) by mentioning one more book: my own Terms of Respect: How Colleges Get Free Speech Right (Basic Books, 2025). I’ll be talking about the book with Princeton alumni at events around the country during the year ahead.

3 Responses

Ralph J. Bulle ’72

2 Months AgoA Sobering Read About COVID Policies

As a hard-core member of the progressive, educated elite, I fully subscribed to the efforts to suppress “fake conspiracy theories” about the COVID virus, its origins, and the necessary shutdown of U.S. society, excluding of course essential workers. I read in The New York Times the disdain within the scientific community for “crack” academics who challenged this thinking. And then I read In COVID’s Wake by Princeton professors Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee, and recently recommended by President Eisgruber. It was a sobering realization of the dangers of groupthink, class biases, and vested interests to which we are all subject. Next year’s pre-frosh read?

Mike Stoto ’75

2 Months AgoOn Politics, Policy, and Public Health

Macedo and Lee are right about the failure of the political system, but as I show in a research paper posted on SSRN, their review of the science is seriously flawed.

The authors use a simple statistical analysis to argue that “lockdowns” did not work. The global literature, however, shows that control policies were effective in reducing transmission. In the U.S., 300,000 deaths could have been averted before vaccines became widely available. This suggests that choices by policymakers and the public — generally short of lockdowns — did save lives.

Macedo and Lee’s concern about viewpoint diversity relates to the Great Barrington Declaration, which emphasized the harms of lockdowns and called for protecting the most vulnerable but offered no concrete plans for implementing these ideas. The response from public health scientists, however, explicitly recognized the social and economic costs and critiqued the declaration on scientific and practical grounds.

They have a more compelling case regarding schools, which were slower to reopen in some cities. They attribute this to liberal Democrats, but the scientific and general literature published in the summer of 2020 is remarkably well balanced, with the likely harms and limited public health benefits both clearly identified. Policymakers were balancing benefits and harms, as they understood them.

Macedo and Lee are right to call for a policy process that respects evidence, recognizes uncertainty, and acknowledges legitimate differences in values and preferences. There will always be uncertainty about the epidemiological facts, but public health agencies should be more proactive in generating the information needed to inform policy choices.

Rick Mott ’73

3 Months AgoMisunderstanding How COVID Spread

In President Eisgruber’s review of In Covid’s Wake (President’s Page, November issue), the authors are said to be “skeptical on masks.” That skepticism is justified. In late 2020 Scott Duncan's Canadian military chemical/biological defense group rigorously tested many ear-loop mask types and found them on average to be only about 1% as protective as N95s.

The public health establishment’s initial beliefs about COVID’s spread can be traced to a scientific error of proof by authority figure six decades ago. Alexander Langmuir, legendary CDC epidemiologist, disparaged and ignored the work of William Wells, an engineer (yay!) from Harvard (boo!) who published proof that tuberculosis was transmitted by air in 1962. Sadly, Wells died in 1963 and was unable to carry on the fight. A 5-micron size limit became the public health definition of “airborne” to this day. The history was dug up by Katie Randall, then research assistant to Virginia Tech air pollution scientist Linsey Marr, who had convened a call in collaboration with Australian air-pollution researcher Lidia Morawska with the WHO and CDC in April 2020. They argued that COVID was in fact airborne and 6-foot separation was useless, but were ignored just like Wells. Randall and Marr published in December 2021, and their story should resonate with Macedo and Lee’s audience. An excellent and readable summary can be found in a Wired article written by Megan Molteni entitled “The 60-Year-Old Scientific Screwup That Helped Covid Kill.” As the phrase goes, those ignorant of history are doomed to repeat it.