Princeton Aerospace Alumni Stick a Lunar Landing on First Attempt

Tom Markusic *02 co-founded Firefly Aerospace, whose Blue Ghost lander carried 10 payloads to the moon

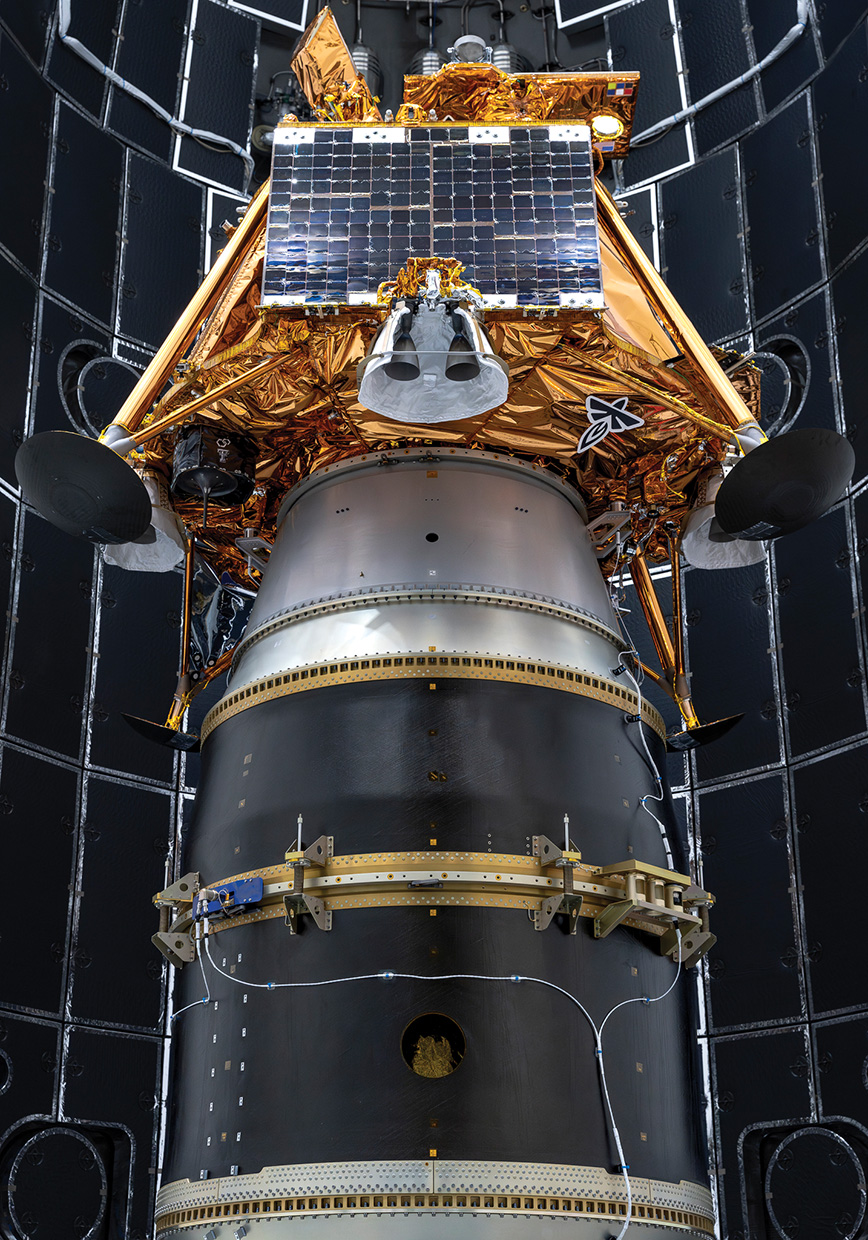

Kevin Tong ’22 was understandably delighted as his team prepared for the March launch of the lunar lander Blue Ghost. Just a few years out of Princeton and now working for Firefly Aerospace, he was one of two propulsion systems engineers at Cape Canaveral in Florida who completed the final checks on the lunar lander. “It was pretty cool that I was one of the last people to touch it before it went to space,” he says.

Tong is one of several alumni of Princeton’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Firefly, co-founded by Tom Markusic *02. Will Coogan *18 is Blue Ghost’s chief engineer; Mike Hepler *20 helped the team meet NASA requirements for contracts; and Candace Do ’24 contributed to the Blue Ghost lander through an internship at Firefly.

Blue Ghost completed more than 14 days of surface operations (346 hours of daylight) and just over five hours of operations into the lunar night. The lander carried 10 payloads that conducted experiments for the length of a lunar day. Among the payloads: a drill looking at thermal gradients below the surface and tests for a sample collection mechanism. Though several moon-landing attempts have been made by commercial companies, only Firefly’s Blue Ghost stuck the landing without tipping over on the first attempt.

This is no small feat because while simulations can give engineers a close approximation of what to expect, testing lunar landing technologies on Earth does not cover every eventuality. For example, the shadows cast by the lander weren’t as crisp as the team expected because it’s hard to predict how shadows play across the lunar surface and difficult to test behavior accurately. Fortunately, this didn’t trick Blue Ghost’s navigation system.

Preparing for their first successful lunar landing took close to four years of work, and the last few minutes of descent were especially suspenseful, Coogan says. “Once you start coming down, there’s not really a whole lot you can do to successfully intervene if anything goes wrong because there’s about a three-second delay between getting data and issuing a new command to the vehicle,” he says. Most of his job was to make sure everything’s well balanced so one system is not over-optimizing to the detriment of the overall vehicle. For example, adding materials to the lander’s structure can make it stronger, but also adds to the weight. “We can make a structure that’s almost invincible, but which is too heavy to land,” Coogan says. “One of my responsbilities is to make sure that no one system is so good that it hurts another.”

Before the Blue Ghost missions could even get going, the Firefly team had to go through the long, complex, and difficult process of submitting proposals to NASA. “We needed to show what the vision was and that we were technically credible to carry out the mission,” Hepler says. The mission was one of three that Firefly was awarded through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative. The others are scheduled to launch in 2026 and 2028.

The challenge of synchronization might have been massive, but Firefly team members solved it with a very human-centric approach, Hepler says. A weekly “Moon Walk” update about the various pieces of the project broke up the pace of what was otherwise a very intense and demanding technical and organizational challenge. “You really feel like, when you’re in the middle of a team who are all building something ambitious, there is a sense of wonder and an idea of service that are integral to building something big,” Hepler says.

Markusic, who was CTO at Firefly, is a SpaceX alumnus. He says space ambitions can’t find velocity until you actually go to space. The key is to make the process more economical and reliable, which is Firefly’s primary focus. Markusic has moved on to found Frontera, where he hopes to work on the next generation of aircraft, transitioning away from conventional vertical rockets.

The CLPS program helps NASA by providing some near-term capability to return to the moon ahead of the more ambitious human space flight mission. “It allowed us, as a nation, to get some early data that would be supportive of human missions,” Markusic says. The program is about incubating the next Boeing or Lockheed Martin.

Hepler says CLPS is a great example of public-private partnerships done well. Since NASA wants to focus on new knowledge from lunar experiments, it can contract companies to do the work of sending a lunar lander and piggyback on such missions. In turn, small companies get a seat at the table. They can raise money, build a team and hardware, and prove that they are not a startup company anymore.

“If done right, there’s a beautiful synergy between the government and the private sector, and neither can really do well without the other,” Markusic says. “The government excels in establishing the fundamental research and development projects that undergird the next generation of technology.”

In the meantime, Tong and Coogan are looking forward to Firefly’s next mission, which will be a two-stage spacecraft configuration. One component, the Blue Ghost lander, will touch down on the far side of the moon and operate government and commercial payloads for more than 10 days on the surface. The other module will function as a lunar satellite relaying communications from the lander back to Earth.

1 Response

Tim Barrows ’66

5 Months AgoCongrats — and Future Steps for Lunar Landers

Congratulations to Firefly! However, this achievement leads to a question. What are the prospects that we could have a lander that can survive the long lunar night and operate for months and not just two weeks?