Princeton Fights Opioid Crisis With Resources and Student Activism

‘The truth is that college campuses are often the first place that students start experimenting with drugs,’ said Vinayak Menon ’27, founder of the Princeton Overdose Project

The number of people who died from an opioid overdose in the U.S. in 2022 (more than 81,000) is about 10 times the number in 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In January 2023, the opioid crisis touched the Princeton University community directly when Maura Coursey, a School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA) graduate student, was found dead due to mixed drug toxicity, including fentanyl, a potent yet inexpensive synthetic opioid.

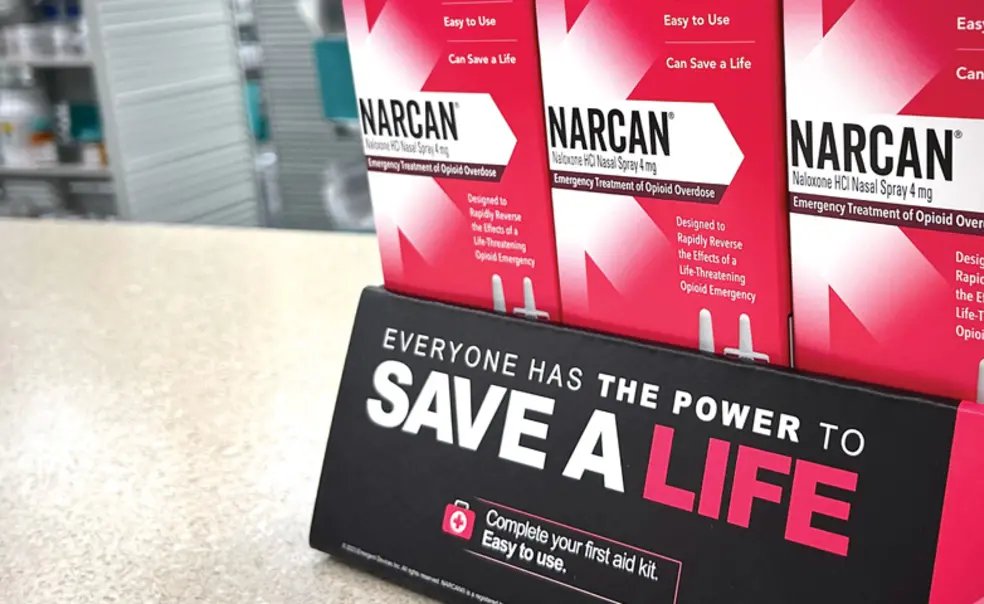

Since then, in an attempt to address the issue, the University has made resources available, and students have been proactively meeting to volunteer locally, discuss harm reduction strategies, and participate in trainings on topics such as how to use naloxone — a medicine that reverses or reduces the effects of an opioid overdose.

“The truth is that college campuses are often the first place that students start experimenting with drugs, and it’s a time of great vulnerability,” said Vinayak Menon ’27, president and founder of the new Princeton Overdose Project, a student volunteer group that falls under the Pace Center for Civic Engagement. “What we want to do is try to ensure that students are as safe and secure as possible, and that we’re doing everything that we can to meet their needs.”

Menon has been volunteering for drug overdose prevention initiatives since a string of overdoses occurred at a high school near his hometown of Suwanee, Georgia. When he arrived at Princeton, he couldn’t find any student groups focused on tackling the opioid crisis, so he started the Princeton Overdose Project.

Menon was surprised by the level of student interest. The group, which was established this fall, has 60 members, mostly undergraduates, who meet weekly and interact with organizations like the Princeton First Aid & Rescue Squad (PFARS), develop ways to broaden campus awareness, research policy initiatives, and volunteer off campus to make kits containing naloxone with the New Jersey Harm Reduction Coalition.

The coalition is headed by executive director Jenna Mellor *20, who received her master’s in public affairs from SPIA and credits her time there as integral to establishing the organization.

Mellor joins the CDC “and so many public health experts” in calling for saturation of naloxone, because “we want naloxone to be nearby, and that means we have to have it out in communities in incredibly large volumes.” She recommends visiting NEXTDistro.org to find out where to locally request supplies.

Her advice for the University is two-fold: “making sure that harm reduction is part of campus culture and these supplies are as easy to get as condoms,” as well as “leveraging its reputation and academic pedigree to make harm reduction and drug policy reform more socially acceptable.”

In 2023, Princeton received naloxone from the state and began distributing it to anyone who requested it, according to Kathy Wagner, associate director of health promotion and prevention services at University Health Services. Beginning in January 2024, McCosh Health Center made fentanyl testing strips — which check other drugs for the presence of fentanyl — and naloxone available in an open-round-the-clock vestibule.

According to University spokespeople Jennifer Morrill and Michael Hotchkiss, 340 naloxone and 226 fentanyl testing kits were distributed between the start of the program in November 2023 and the end of the 2023-24 academic year; as of early December, 85 naloxone and 78 fentanyl testing kits had been distributed this adademic year.

Vincent Jiang ’25, president of Tower Club and of the Interclub Council, said Princeton should include overdose prevention information with the alcohol training mandated for freshmen, as well as provide training to eating club officers. At least one representative from every eating club attended a fall naloxone training — which the Princeton Overdose Project helped arrange — conducted by an EMT from PFARS.

“We are trying to be as proactive as possible with this issue,” said Jiang.

The Princeton Overdose Project has requested that the University provide naloxone in campus AED cabinets, and the group is also considering requesting naloxone at all blue light emergency phones.

No responses yet