Princeton’s ‘Freedom Libraries’ Deliver Books to Incarcerated Readers

These were the first libraries opened in the New Jersey correctional system

Two years ago, Dean of Libraries Anne Jarvis saw a one-man performance at Princeton that revealed the power of books to her in a new way.

That show was Felon: An American Washi Tale, which Reginald Dwayne Betts performs in correctional centers and also performed at Princeton in 2023. Betts, a poet and lawyer and MacArthur fellow, is also founder and CEO of the group Freedom Reads, which puts libraries in prisons.

Along with his own books, including a memoir and poetry collections, he created the theater piece about his time in prison and the role books played during his incarceration.

“I was moved by Dwyane’s story and how access to books changed the trajectory of his life,” Jarvis says. “It was clear to me that the library and the University should support this initiative.”

Last year, in a collaboration with the Princeton University Library, the University’s Lewis Center for the Arts, and its Prison Teaching Initiative, nine Freedom Libraries were placed in the Garden State Correctional Facility, a New Jersey Department of Corrections state prison. These were the first libraries opened in the New Jersey correctional system. Betts notes that not every prison has a central library; having multiple libraries within a system ensures access as well as community building around the books. Their hope is to create a library in every cell block in every prison in the U.S.

“It felt important to underscore how books can have such a positive impact on a person’s life — stimulating imagination, improving communication skills, expanding knowledge, and supporting continuous learning and growth,” Jarvis says.

She adds, “Being able to play a small part in transforming the lives of incarcerated persons in New Jersey through increased access to books reflects both the library’s and the University’s missions.”

Jarvis believes Princeton is the first academic library to support Freedom Reads, adding, “and I am hopeful that we won’t be the last.”

Freedom Reads is inspired by Betts’ own experience serving a nine-year sentence in prison as a teenager after pleading guilty to carjacking. When he was sent to solitary confinement, he says, he could not have books.

But the men there had created a way to read anyway, through dropping books by rope in a pillowcase.

Through this, Betts learned how powerful storytelling can be. Books help people tell a story to themselves and to the people they love, “not just about the content of the books, but about why books matter,” he says, “and why they connect you to strangers.”

Betts’ Princeton connections include being in residence as a guest artist in 2021 at the Lewis Center for the Arts, where he created his one-man theater piece, which was adapted from his poetry collection Felon. The play touches on a handful of topics like fatherhood and experiencing life with a criminal record. Like much of Betts’ work, which spans multiple artistic endeavors, this play uses a variety of methods to get themes across, including theater, poetry, and Japanese paper making.

Jarvis said the Freedom Library books are selected by Freedom Reads and include poetry, novels, essay collections, and classic works like Homer’s The Odyssey and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

The New Jersey libraries were placed in housing units with a 500-book collection.

The nonprofit has opened more than 413 Freedom Libraries in 44 adult and youth prisons across 12 states, according to the group. The purpose is to give incarcerated people some freedom of mind to imagine new possibilities for their lives, and to empower people through literature.

For the New Jersey libraries, Princeton’s contributions were “vital,” Betts says. Through their support, especially at the Garden State Youth Correctional Facility, “We brought Freedom Libraries to the lives of young people, some who may read their first book from the library.”

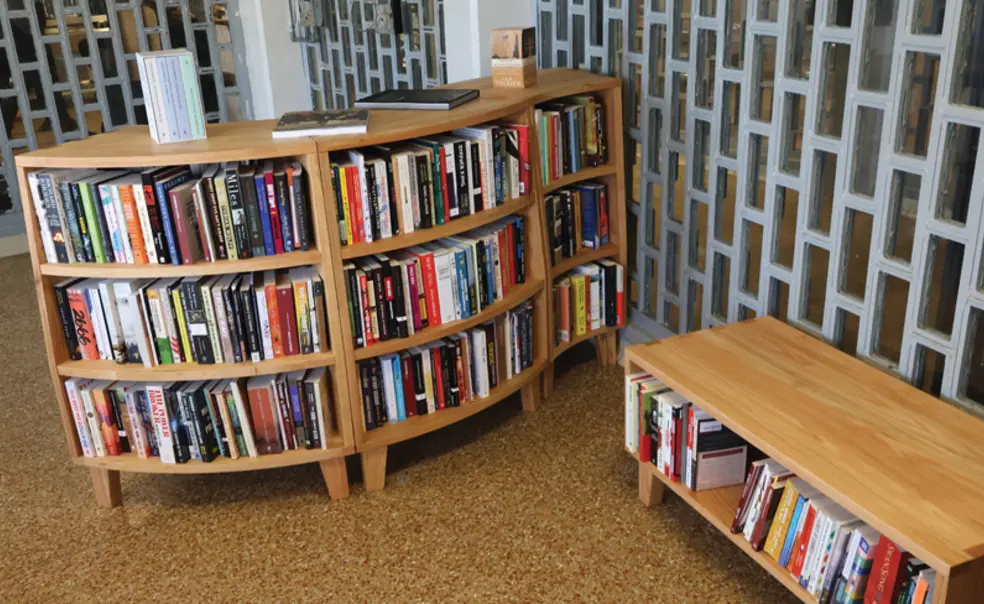

Freedom Reads brings not only books into prisons but also handcrafted bookcases, designed to stand in opposition to chaos. They are made out of maple, cherry, oak, or walnut and curved to be able to be in the middle of the space, to inspire conversation and community building.

According to the group’s website, “The library is a physical intervention into the landscape of plastic and steel and loneliness that characterizes incarceration.”

“Beauty and care matter in the same ways that it matters to all of us,” Betts says. “Aesthetic beauty is healing, is a relief against the extreme pressures of our lives, [and] allows us to discover ourselves.”

The bookshelves’ design, he says, “gave us a pathway toward what we consider a profound physical disruption of the harshness of prison.”

No responses yet