Professor Emerita Martha A. Sandweiss Uncovers Civil War Mystery

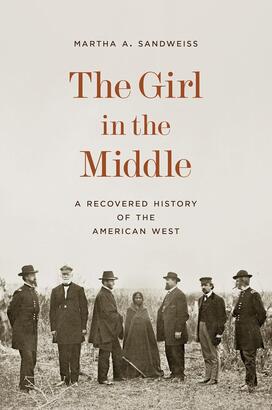

The Book: The Girl in the Middle (Princeton University Press) is a portrait of the tumultuous American Reconstruction Era and westward expansion. Princeton professor emerita of history Martha A. Sandweiss tells the story of several figures of this time, including celebrated Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner. Gardner took Abraham Lincoln’s iconic portrait, as well as a photo of six federal peace commissioners circled around a young Native girl bundled in a blanket. The Girl in the Middle goes in search of this mysterious young woman, making unexpected connections to the men around her and ultimately bringing a new perspective to this period while also revealing the nation’s struggle to discover its identity as it pushed westward.

The Author: Martha A. Sandweiss is a professor emerita of history at Princeton University, where she founded the Princeton & Slavery Project, an exploration of Princeton’s historical ties with slavery. Her particular areas of historical focus lie in the American West, visual culture, and public history. Sandweiss is the author or editor of many books on American history and photography and is the recipient of numerous awards such as the Organization of American Historians’ Ray Allen Billington Award for the best book in American frontier history for Print the Legend: Photography and the American West (2002).

Excerpt:

Sophie Mousseau’s life spanned the period from the Civil War to the Great Depression. Unlike Harney or Gardner, she had no public reputation to rise or fall. She faced the new century as a private person. Circumstance determined how people categorized her. A census taker who encountered her as a child considered her white. Some who knew her while she was married to her first husband, a white man, considered her and her children Indian. Later, as an enrolled member of the Oglala tribe, living on the reservation at Pine Ridge, she become known as a mixed-blood. She did not change. The labels appended to her did.

Some descendants of her thirteen children still live in and around Pine Ridge. Others live scattered across the country. No relatives who knew her are still alive, but a few of her great great-grandchildren have become ardent genealogists, trying to piece together the story of her remarkable life from scattered family stories and government records — and now from a photo graph.

I started with an unidentified child. I found Sophie.

At least I think I did. This book was all but finished when a halftone reproduction of another photo graph turned up, this one with the name “Sophia Mosseau” in the printed caption of a picture of people posed in front of the Oglala Boarding School in January 1891. If the caption is correct, this would be the only identified photo graph of Sophie. Her descendants have none, though she lived into the 1930s when family photo graphs were a ubiquitous feature of American life, even on rural Indian reservations.

It’s a hard call. The identified woman is almost twenty- three years older than the unidentified child. She is dark complected and short like the girl, but the facial matchup is neither obvious nor improbable. I tried various facial recognition programs to assess the likelihood the two photographs depict the same person. Mostly what I learned is that the computer algorithms were not developed with monochrome 19-century photographs, dark-complected subjects, or non-European peoples in mind. The most definitive computer findings informed me that the woman in the 1891 photo graph was a man, and the 8-year-old in Gardner’s photo graph

was a 30-year-old.

For me, however, the evidence adds up. A grand son identified the child in the photo graph. Archival research further confirms that Sophie’s family was at Fort Laramie when Gardner showed up with the peace commissioners and that her father knew two of those men. But what is at stake in knowing this is her?

The presence of an unidentified girl in the photo graph prompts us to think about others like her and about the family lives of the known figures she encountered that day Gardner made her picture. She pushes us to be attentive to the other Native children and women so often left out of American military and diplomatic history, and reckon with how federal policy

shaped the options for the thousands of Native people who came into Fort Laramie in 1868. She pushes us to remember that the peace commissioners standing beside her were public figures who also had private, family lives. Harney, we discover, got away with the murder of a young woman named Hannah, and Tappan took in an orphaned Cheyenne girl. If we start asking questions about the man who photographed the child, we end up with stories about a utopian colony on the midwestern frontier and a reevaluation of the great photographic album of the Civil War.

Even without a name, the girl in the photo graph leads us into a world shaped by violence. The sort of violence perpetrated by opposing armies, the vindictive violence waged against unarmed civilians, the violent frustration of hungry people, the domestic violence waged inside homes and crowded dining halls. She stands in the picture surrounded by men who all fought in America’s bloody Civil War and got caught up in the military violence perpetrated against Native peoples out west. She poses for a man who made his reputation photographing the Civil War battlefields and the execution of some convicted assassins. She stands beside a man who

murdered an enslaved woman and next to another who took in a young girl orphaned in a military assault. Those men are all there in connection with a Peace Commission, whose very name and mission speak to the existence of a violent situation to be resolved.

But knowing who that girl is shifts things, refocusing our attention from the men around her to her. In centering her, we decenter them. Sophie’s living descendants have had scattered stories, but no picture with which to visualize their ancestor. Conversely, the viewers of Gardner’s photograph have had a face without a name. Put the name and the face together, dig into the historical records, and a largely forgotten life becomes more knowable.

Sophie’s life was born of violence. Her parents’ chance meeting in the aftermath of Harney’s assault at Blue Water Creek in 1855 doesn’t negate the horror of the massacre or minimize the trauma experienced by the survivors. Yet their long marriage reminds us that violence can have unintended consequences: it disrupts families, moves people around, and brings different people together. In this case, Harney’s vindictive military assault on unarmed Lakota families established the conditions for M. A. Mousseau and Yellow Woman to meet and create the family that brought young Sophie into the world and into the picture.

Sophie’s parents knew some of the peace commissioners gathered at Fort Laramie; the unintended consequences of the violence ripping across Indian Country ensured that. Harney and his troops had wounded her mother at Blue Water Creek, and Harney later employed her father. A tense subtext of memory haunts their meeting in 1868, as M.A. urges his daughter to pose with the self-confident military man. We can know that; the photographer likely did not.

Another, more recent act of violence brought Sophie into Gardner’s orbit. Just weeks before, a small group of Lakota men, frustrated by the increasing number of white immigrants competing for their land and food, had destroyed the Mousseaus’ road ranch. The raid not only led M.A. to hire Commissioner John Sanborn as his attorney but also drove the Mousseau family into Fort Laramie. There, Mousseau found horses stolen from him years before. And there, a young multilingual child raised in remote parts of Dakota Territory ran into one of the nation’s best known photographers and some of its most widely known Civil War generals. Those men Sophie met the day Gardner photographed her put her just one connection away from the murdered President Lincoln (and any number of other leading political, cultural, and military figures). Though she and her father couldn’t know it, their presence put Gardner and Sherman just one connection away from the man who would become the premier of Quebec. Everyone trailed their pasts behind them as they moved across the west to prosecute war, execute peace, run a trading post, or make a photograph. Personal ties and connections could be a bit like trains or telegraphy: as people traveled — as soldiers or immigrants, as traders or children trailing their parents — they brought knowledge and experiences that shrank distance and brought the faraway near.

Violence set people in motion. And people in motion made for strange bedfellows.

Excerpted The Girl In The Middle: A Recovered History of the American West © 2025 by Martha A. Sandweiss. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Reviews:

"Sandweiss. . . shows her extraordinary ability as a historian-detective." — David Steinberg, Albuquerque Journal

"Compelling. . . . A truly revealing image of American empire." — Literary Hub

No responses yet