Q&A: Engineering Professor Yiguang Ju on Electric Vehicles

Ju says EVs are the future, but the technology’s not there yet

Switching from gas-powered to electric vehicles is one of the key pieces of the U.S. push to lower carbon emissions. Currently, less than 1% of the 250 million vehicles on the road in the U.S. are electric vehicles, according to Climate Scorecard 2022 data. Yet the federal government plans to end its purchase of gas-powered vehicles by 2035.

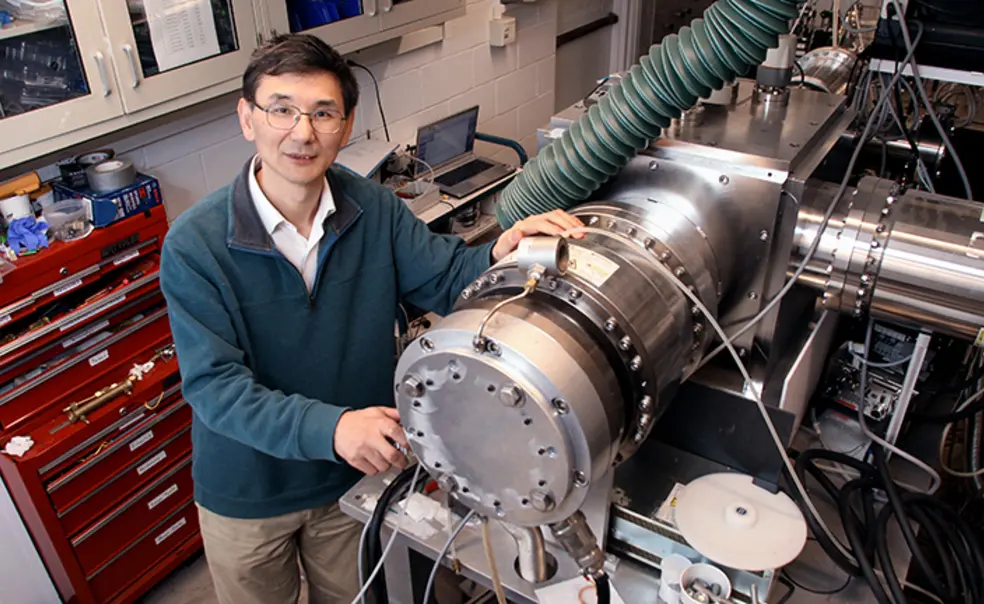

While zero-emission vehicles are the future of the auto industry, Yiguang Ju, a Princeton professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and director of the Program in Sustainable Energy, argues there are still a number of challenges to overcome. Ju spoke with PAW about those issues, the environmental impact of EVs, and his concerns about EV batteries.

Tell us a bit about your research and what you’re working on.

My research is in energy. We’re working on low carbon fuels, plasma assisted combustion and manufacturing, and energy materials. I also co-founded a few companies focused on this research: HiT Nano, Princeton NuEnergy, and Polymer-X. Battery fires are a major issue, so the research I’m interested in now is to see if we can design the cathode materials that can block oxygen release from the cathode to prevent spontaneous battery ignition.

What’s the current state of electric vehicles in the U.S.?

I don’t know whether I’m the right person to answer that question, but I’ll try my best. In terms of battery, I think that Tesla is clearly the leader in that area. They’re making batteries with high-nickel cathode materials that have high energy density, using the materials provided by Panasonic (Tesla’s main battery manufacturer). But there are challenges. One is the price at more than $100 per kilowatt hour, the energy density (which relates to how long the battery lasts), and fire safety. The question that researchers are trying to solve is how to better reliability and recyclability of batteries for electric vehicles.

What is being done to combat these issues?

Today, we have a lot of electric vehicles and batteries. The question is how do we handle the aged batteries? So one way is to take it apart, burn it, remove the carbon electrolyte, and dissolve it into acid so you can recycle the metals. This requires a lot of energy and you’re causing environmental impact, so it’s a high cost and high energy process. At Princeton NuEnergy we came up with a process using plasma as a non-equilibrium reaction to directly recycle the cathode materials without breaking it down into atoms and molecules.

What impact do electric vehicles have on the environment?

Electric vehicles use renewable electricity so that dramatically reduces the carbon emissions. Today in the United States, electricity is still mainly produced from fossil fuels, around 60%, and it’s mostly coal and natural gas. Electric vehicles have to get electricity from our power grid. Also, even though electric vehicles have higher efficiency, in places like New York and New Jersey, they still need to generate heating because it’s cold. Converting electricity to heat is really not efficient because the efficiency for coal to produce electricity is only about 38% on average in the U.S. That’s really bad and probably generates more CO2. For natural gas and methane to produce power electricity in the United States the efficiency is around 50%. So, I think electric vehicles will dramatically reduce carbon emissions under the condition that the electricity produced is by renewable energy. When comparing that to hybrid vehicles, I think hybrids are probably better today in cold areas.

We’ve all heard horror stories of self-driving EVs malfunctioning and having other issues. How worried should we be?

Well I think fully automated driving is the future and technology will improve as the time keeps going, but today, I think that the technology is not there yet. For now, cars that are completely self-driving is a miss concept. I had the experience of driving with a friend in a Tesla that was self-driving and the car hit the concrete separator of the highway on a rainy day. I thought I was going to get killed. So, you can see there are many holes. Rainy days, complicated events, and unexpected environments are very difficult for automated processes because they weren’t trained on those specifics.

What are common misconceptions you hear about EVs?

I think one thing you hear a lot is that electric vehicles are safer than gas vehicles. I think that is wrong. In combustion engines the fuel and air are separated and you never have to worry about the autoignition when you park your car at home. With electric vehicles, if you’re charging it at home it could spontaneously ignite. The other misconception is that electric vehicles definitely have lower carbon emissions than hybrid vehicles. I think the misconception comes in because it depends on where you are and how you produce the electricity. If you are in California or Hawaii that’s true, but if you’re driving in New York City and New Jersey where it’s cold, your mileage is dramatically down so it may generate more carbon emissions than a hybrid vehicle.

What should people look for or keep in mind when shopping for electric vehicles?

I would suggest for people to buy a vehicle that is resistant to fire because I do combustion and fire research, so the number one thing I’m worried about is fire safety. It’s probably better to buy electric vehicles with lithium iron phosphate batteries, not the high energy batteries using high-nickel cathode materials.

Any other thoughts on EV batteries?

Battery manufacturing is really dominated by Eastern Asian countries. The United States is far behind. I think that America needs to develop new technologies in battery manufacturing and should enact an innovation act to address these issues. It would be a great opportunity for the United States to establish its leadership in battery manufacturing.

Interview conducted and condensed by C.S.

3 Responses

Larry Tuttle ’68

2 Years AgoElectric Vehicles ARE the answer

Professor Ju’s opinion about EVs in the April issue is a bit confusing, There are too many sources of information that answer yes to the question, “Are Electric Vehicles the Answer.” The fact is, just about every vehicle manufacturer in the entire world today has concluded that EVs are the answer.

Also, about the impact of fuel source, the total impact to the planet of vehicles needs to be analyzed end-to-end, not just on the fuel, but on the total life cycle of the vehicle. This includes manufacturing, distribution, maintenance, and recycling. Think of the environmental impact of refineries, iron mines, steel mills, gas stations, junk yards, and lithium recycling, for example. And think of the healthcare benefits of reducing air pollution.

About self-driving cars, take McKinsey’s 2023 report, “Autonomous driving’s future: Convenient and connected.” Arguably the top consulting firm in the world believes we will solve these problems.

Let’s hear about how Princeton’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (my department) is helping solve some of the problems presented by EVs.

John Wright *98

2 Years AgoAnswers Based on Personal Anecdotes and Rumor

I read the answers from Professor Yiguang Ju with dismay. I would expect someone leading the Sustainable Energy program to be able to provide answers backed up by fact instead of personal anecdotes and speculation. Just to take a few answers:

Per 100,000 vehicles sold, internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles catch fire at a rate about 100 times that of electric vehicles according to insurance industry research. And of course research into batteries (e.g. lithium iron phosphate) will lead to even safer batteries. And yet Prof. Ju perpetuates fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

He conflates self-driving algorithms with electric drive chains.

He guesses that an EV in New Jersey during winter would have more emissions than a similar ICE vehicle. And yet this topic has been investigated thoroughly by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). You’d have to have 100% coal generated electricity and the heat in the EV on in winter (~0.3 kg/mi for ev compared to similar ice vehicle of 0.5 kg/mi). And this is not the energy mixture in New Jersey, which is mostly natural gas and nuclear.

I would suggest the director spend more time coming up to speed on the literature instead of guessing at the answers to these questions.

Graham Turk ’17

2 Years AgoWe Have Already Overcome Barriers to Rapid EV Adoption

I deeply respect Professor Yiguang Ju as a researcher, but many of his responses in the April issue (Research) are either false or misleading, starting with the claim that hybrids are less carbon-intensive than electric vehicles (EVs) in cold-weather states. The Union of Concerned Scientists publishes a tool every year that converts a typical EV’s emission intensity into miles per gallon of gasoline (evtool.ucsusa.org). In Boston, Massachusetts, a cold city where about 60% of electricity comes from natural gas power plants, an EV gets the equivalent of 116 miles per gallon. Fewer than five states have EV emissions below 50 mpg, and even those are likely to improve as coal and natural gas plants are replaced by renewables.

Ju also expresses concern over price. Yet a recent report by Atlas Public Policy showed that the total cost of ownership for an EV purchased today is already lower than its gasoline counterpart.

Finally, safety. Ju recounts a personal anecdote of an autonomous car crashing into a concrete barrier. EVs and self-driving technology are often mentioned in the same conversation, but that incident had nothing to do with the car being electric. And regarding fire risk, every vehicle sold in the U.S. must undergo rigorous testing and meet the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards.

Ju’s remarks risk perpetuating the false narrative that EVs are not ready for mass adoption. But if you purchase an EV, you will save money and significantly reduce emissions. EVs are not only the future. They are the best choice today.