Q&A: Languages Expert Dong Li Explains the ‘Living’ Craft of Translation

‘I don’t think AI can translate the unpredictability of poetry, the linguistic surprises’

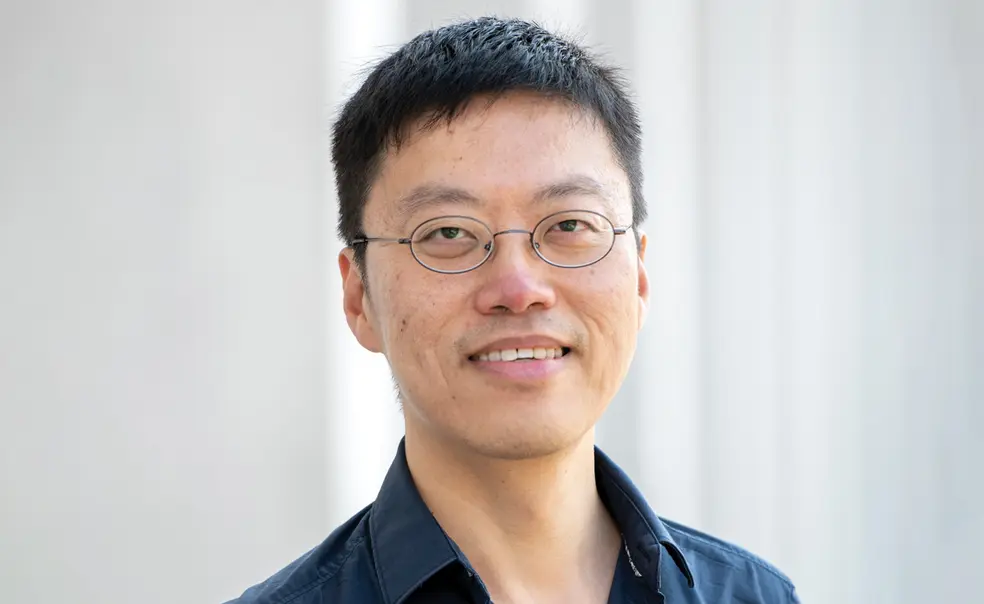

Through Princeton’s Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication, students can take courses about (and minor in) translation, attend topical lectures, and receive funding for translation projects. Every semester, the program, which is housed within the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, also hosts a translator-in-residence. PAW sat down with the fall 2025 resident, Dong Li, to ask about his work.

Li was born and raised in China, came to the United States for his bachelor’s degree in comparative literature and his master of fine arts degree in creative writing, and then settled in Germany, where he has lived for more than a decade. He primarily translates Chinese poetry into English, but also translates from English, French, and German. He’s currently working on several projects, including translating his own forthcoming poetry collection — The Bench, a follow-up to his debut, The Orange Tree — from English into German. He hopes to encourage more students to explore translation.

What brought you into translation?

I just love languages.

Have you always?

Yeah. I feel like it has opened not just a world, but worlds to me. I learned English through translating contemporary poets from mainland China who have been underdogs. I think it’s important — voices which have not been heard. Still, I try to only translate people who are not famous or very well-known in the target language, or whoever’s doing innovative stuff.

Does your process vary if you’re translating into English versus another language?

It depends on the project. For me, I really want to know the sound of that particular author. Sometimes I will visit places that are important for a particular book. I really try to get at the emotional landscape, which is often reflected in the physical landscape.

It sounds like you really put yourself into these translations.

I see it as a new life of this work. I have to be super committed because sometimes I’m also like an agent. I promote the authors in foreign countries, trying to organize events and readings.

Has AI affected the field?

I don’t think AI can translate the unpredictability of poetry, the linguistic surprises. In poetry, you try to do things that have not been formulated yet. Yesterday, Michael Moore, a very established translator from Italian, demonstrated in class, you can give AI orders — “translate this more colloquially,” but students were saying, “AI cannot translate emotion.” AI has been fed text from lots of consciousnesses. If you want to hear an author’s voice, it’s got to come from one consciousness.

Do you feel like the field gets the respect it deserves?

A lot of translators are also activists in the field, fighting for rights, especially more commercial publishing, saying the translator’s name should be on the cover, which I agree. Translated literature requires creativity as well. There is this false comparison — if it’s a good translation, people say it reads like the original, but I feel that’s not right, because translation is its own genre. You are making the translators invisible.

What brought you to Princeton?

I find the setting fantastic. I get encouraged by the professors and students, who are always very hardworking, very kind, and generous with their time.

I admire translators who have been here. I just mentioned Michael Moore, who was the first translator-in-residence here. I think I’m the 18th.

I run four workshops for the class Translation, Migration, and Culture. I try to put together interesting texts to translate. Sometimes I have a sample translation from established translators, but sometimes students come up with better ideas. I just told them, embody your translation, put your soul into it. You are not just translating one word and another word, you’re translating a living thing. Make it alive.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

1 Response

Wolfgang Konrad *93

1 Month AgoInvitation from the Princeton Alumni Association of Germany

I am the president of the Princeton Alumni Association of Germany, and I would be delighted to include Dong Li in our activities.