Q&A: Laura Kahn *02 on COVID’s Spread and How We Defeat It

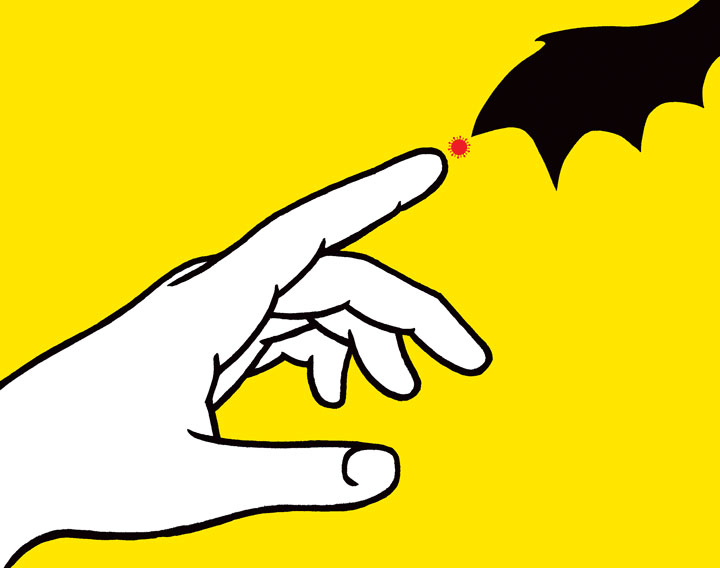

COVID-19 started in an animal host; new policy could help prevent the next outbreak

What are the most important things for decision-makers to know about the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19?

First, its origin: The virus is a betacoronavirus, a similar genus to SARS [Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome] and MERS [Middle East Respiratory Syndrome], and one that’s very common in animals. There are several theories as to the host of this disease, but what’s more important is the root cause of why zoonotic diseases emerge. In all cases — SARS, MERS, and now SARS-CoV-2, also Ebola, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease — they emerge directly or indirectly because of humanity’s demand for animal protein, specifically in the form of meat.

Second, its case-fatality rate: MERS and SARS had higher fatality rates — about 34 percent and 10 percent — than COVID-19, which currently ranges between .25 percent and 3 percent. It could be even lower, since that number doesn’t include the many asymptomatic cases.

Finally, its spread: Because people, especially healthy children and young adults generally have milder symptoms, they might be more likely to spread the disease to those who are more vulnerable.

How do viruses like SARS-CoV-2 jump from animals to humans?

Our most intimate way of interacting with our environment is eating it — through animal protein, dairy, eggs, or even eating plants, you’re always going to risk consuming microbes that might make you sick. We have known for a long time that there are many viruses lurking in the environment, particularly in wild animals. In the case of SARS and COVID-19, these viruses originate in horseshoe bats, and are then spread to humans via other animals. Capturing animals, destroying their habitats, selling them in large, live animal markets, and eating them is a time bomb for more diseases like these to emerge into human populations.

To move from one host species into another, the virus’s surface proteins must be able to recognize and bind to the receptors on the host’s cells. Once the virus enters the cell, it can hijack the cell’s machinery to make new viruses. The SARS-CoV-2 virus uses a human receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). It is the same receptor that antihypertensive drugs called ACE inhibitors use. So people taking ACE inhibitors have been advised to talk to their doctors about whether or not they should continue taking them. MERS uses a different receptor.

What could have been done to prevent a zoonotic pandemic like this from starting in the first place?

My book One Health and the Politics of Antimicrobial Resistance, and the One Health concept that I develop there and elsewhere, shows how human and animal and environmental health are linked. This link may seem obvious, and it has been recognized by indigenous peoples around the world, but in practice, our institutions are strongly speciesist. This is to say, they only care about humans without thinking about other animals. When we do that, we miss a huge part of our world.

In this country, for example, there’s no CDC for animals: The USDA cares about food animals, the CDC studies rabies, and the Department of the Interior does some surveillance of fish and wildlife. We need coordinated surveillance of wildlife, domesticated animals, and people to monitor the emergence and spread of diseases. Ideally, we should have a department of animal and environmental health that monitors the health of all animals (companion, livestock, and wildlife) because their microbes impact our microbes. And we need more funding for research on animal health and disease.

In questions of human medicine, vets are generally ignored, even though they have important expertise in many of the problems we face today, from climate change to zoonotic diseases. We need to recognize that animal health is important for our own health and well-being. If we just focus on humans and make assumptions, then we’re not going to make any effective policy.

You’ve studied how political leaders handle pandemics. How are U.S. leaders handling this one?

Writing my book Who’s in Charge, about leadership during public-health crises, I found that whether a political leader like the president or an expert appointee like Dr. Fauci was the face of the government’s response to the crisis, it was important for both leaders to act in concert, and for the political leaders to listen to the experts.

At the beginning of this crisis, the U.S. federal government made every mistake you can make. By playing down the severity of the pandemic in early press conferences, President Trump created large swaths of the population who thought it was not as serious as it was. In fact, the CDC’s tests were faulty to begin with and slow to roll out, so we have to assume that there are actually many more cases in this country than we know about. And by acting like closing borders would prevent the crisis and calling the virus a “Chinese virus” or “foreign disease,” our leaders created scapegoats, which stigmatizes the disease and makes testing and treatment — and public-health responses like social distancing — even harder.

This president also gutted the CDC; he removed the best experts and the infrastructure that we need to have ready. People forget that these bureaucrats are extremely important in our safety and well-being.

Will social distancing as practiced currently be enough to slow the outbreak?

It’s hard to predict the future. I’m optimistic about finding an effective drug to treat the infection. However, because the U.S. has been so slow to initiate widespread testing, we will have many more cases than if we had implemented stringent airport screenings, testing, and quarantine. This was a monumental failure of the Trump administration. In the short term, it’s going to get worse before it gets better. Largely, state and local governments have had to step up to the plate and develop their own policies without federal guidance or assistance.

The Constitution places the responsibility of public health on the shoulders of state leaders, and that means the governors are legally in charge during public-health crises. Local governments implement the responses. When the Constitution was written, it was 75 years before the germ theory of disease, and modern medicine didn’t exist. The founders had no notion of microbes. Now we know that microbes don’t recognize political borders, which is why the national response is so important. But in some ways, we may be better off having public-health leadership as a state and local responsibility with this current crisis.

What can individuals do to keep the pandemic from spreading in their communities?

The people who are most at risk are those who are older or with chronic illnesses, and we want these people to be protected as much as possible, which is why everybody should be sheltered in place. We don’t want to wait until the hospitals are completely overrun — we want to break the chain of transmission as soon as possible. It’s critical to curtail everything: Cancel trips, don’t go out, just basically hunker down and break the chain of transmission.

What can we learn from this pandemic about what we owe one another?

For the remainder of this crisis, we need to pull together as a community, to remove all stigma of who you are or who you voted for, your race, your religion. This is a national crisis, and a global crisis, so we need to protect one another.

Finally, we need to learn from this pandemic to address the other ongoing crisis, which is climate change. Society is not going to end because of this virus, but climate change has the potential to do that, and we need to be addressing this as such. We need to turn the same sense of urgency we have now in dealing with this pandemic to the ultimate goal of leaving a habitable planet for our kids and for future generations.

Interview conducted and condensed by Bennett McIntosh ’16.

This is a revised version of an interview posted on March 25, 2020.

6 Responses

Walter Weber ’81

5 Years AgoPolitical Checklist

I had looked forward to reading the article, “An Ongoing Crisis” (April 22), hoping to learn new information about the science behind the COVID-19 virus. While there were some informative elements, the bulk of the piece was a checklist of left-leaning political points.

The comprehensiveness was impressive: Trump is a failure; eating meat is bad; treating humans as (way) more valuable than animals is ignorant; experts know best; Trump is really a failure; we need a bigger federal government and more government spending; the Constitution is outdated; Trump is really, really a failure; climate change threatens the end of society.

Some of it was downright laughable in its inconsistency: COVID is an order of magnitude less fatal than MERS and SARS, yet the severity of this pandemic calls for unprecedented measures; closing international borders to stop virus transmission is poor policy, but closing the borders of one’s own home is essential to “break the chain of transmission.”

And experts wonder why so many people don’t trust them to be reliable sources of unbiased information?

George Coyne ’61

5 Years AgoThe Elephant in the Room

I began reading Dr. Laura Kahn’s article on the COVID-19 virus and America’s response to it in the April 22 issue of the Alumni Weekly in the hope that a Princetonian associated with the medical profession might provide a rational and objective analysis. Unfortunately, outside of her medical opinions, Dr. Kahn toed the party line. The only mention of the Chinese Communist “elephant in the room” came briefly in a criticism of President Trump for “scapegoating” by terming COVID-19 a Chinese virus. Of course it is a Chinese virus! That is where it originated, almost certainly in the Wuhan virus research facility. The Chinese government was also responsible, with the complicity of the WHO, for spreading disinformation about the severity of the outbreak for at least six weeks during December and January. This contributed greatly to the slow response of the rest of the world.

President Trump saved thousands of American lives by banning flights from China in late January while at the same time, China likely caused hundreds of thousands of deaths globally by allowing international flights in and out of Wuhan, most notably to Italy, while locking down Wuhan to the rest of China. The Chinese government must be held accountable. Perhaps the tentacles of Communist China reach further into the American economy and into its universities than most people realize.

Dorina Amendola ’02

5 Years AgoDisappointed by Partisanship

Precisely, Mr. Coyne! You took the words out of my mouth (more eloquently too). Very disappointed in the partisanship of that article, and showing more and more in others.

Thomas N. Williams ’77

5 Years AgoPreparing for Pandemics

The “An Ongoing Crisis” article published in the April 22, 2020, PAW contained a number of misstatements and provided irrelevant information that doesn’t pertain to the SARS-CoV-2 crisis. The article completely ignores the culpability of the Communist Chinese regime, the complicity of the World Health Organization, and the lack of preparedness of U.S. government agencies whose funding is actually higher under the Trump regime than under Obama (CDC funding at the last year of President Obama’s administration was $7.2 billion and under President Trump in 2020 $7.7 billion; that hardly counts as “gutting the CDC,” as flatly stated in the article).

The source of the virus is yet unproven, and still controversial. It isn’t clear that the virus is entirely natural or caused by consumption of bats for food. It would be best to say that we don’t yet know. In any case early warnings by Chinese physicians were suppressed, the physicians were imprisoned, and some disappeared. Many false statements were made, then repeated by the WHO.

Secondly in shutting down flights from China early, President Trump took a courageous, appropriate action that undoubtedly reduced the rate of infection and allowed the subsequent quarantine to flatten the curve (which appears to have successfully eliminated the risk of overwhelming our unprepared health care system). President Trump also galvanized the private sector which has, in contrast to our public infrastructure, stepped up rapidly to provide most of the tests and most of the equipment.

Perhaps instead of bashing the current incumbent administration, our Woodrow Wilson School scholars could learn from this pandemic to prepare us for the next one. That would include ensuring that accurate facts and figures get out to the global public, proposing a reserve of imperishable protective and medical equipment, improving the development of testing methods, and setting up a reliable “early warning system” uncompromised by global politics.

Cara Ryan s’76

5 Years AgoWhat a Gem!

Dr. Laura Kahn has the breadth and depth of vision critical to our success in meeting the multi-pronged mess we humans have made. I don’t think I’ve seen anyone nail all the different angles so well: from the environmental to our human/wild animal relations to our political crisis of leadership. Princeton is lucky to have her and her courses should be part of every student’s (preferably including the rest of us) general education.

Donna Nuttall Joe ’86

5 Years AgoAn Article Worth Reading

I actually wasn’t going to read the Q&A with Laura Kahn *02 (Life of the Mind, April 22) because I have been gorging myself on COVID-19 articles and doubted there was anything new for me to learn. However, I am so glad I did — and learn I did.

I found Kahn’s clear and precise discussion about how human and animal and environmental health are linked very informative. I also thought that her suggestion of creating a “department of animal and environmental health that monitors the health of all animals (companion, livestock, and wildlife)” was a brilliant one. I hope people are listening.