“Let music rule the fleeting hour —

Her mantle round us draw;

And thrill each heart with all her power,

In praise of old Nassau!”

— Harlan Page Peck 1862, “Old Nassau,” 1859, verse 2

As someone who has a respectful love/hate relationship with the Orange Bubble, let me fully admit to its virtues when things outside are lousy (floods, government, whatever) and things inside are at their best. And it’s impossible to imagine things in Princeton much better than at Reunions, an anachronism gone so far over the top that describing it to non-Tigers becomes even more difficult over time. Hollywood may be in an era of unbounded special effects and escapist mania that otherwise insults reality, but The Avengers has no edge in suspension of disbelief on a few dozen graduate alumni decked out as orange-lab-coated mad scientists. And the sight of Dr. Joe Schein ’37, at 104 years old, merrily strolling down Elm Drive with the Class of 1923 Cane has the power to cure what we used to call in Sunday School a multitude of sins.

I sang “Old Nassau” exactly six times at Reunions this year, and that’s probably fewer than most people, since I was both at an “off-year reunion” (actually an oxymoron at Princeton) and closeted in prep work for next year’s 50th of the Great Cicadian Class of 1970 much of the time. At Reunions you hear the song incessantly, in various keys, and nobody cares much because, well, everybody’s together singing “Old Nassau.” It works great if you happen to be drinking because it’s a drinking song, complete with choreography; it’s got a nutty warmth because it’s an alma mater that doesn’t mention the name of the school; and at the most basic, it works because you’re engaged with a bunch of close friends (at Reunions, often instant close friends) in a well-meaning attempt to “bid every care withdraw.” That’s actually what it says.History, of course, teaches us that things mucked around by human beings tend to be more complex than that most of the time, and since we’re in the History Corner we should spend a bit of focus and gray matter on that today, before we adjourn for the summer. And in one of the thousands of ironies that form the woof (if the not the warp) of existence, we need look no further than “Old Nassau” to see it.

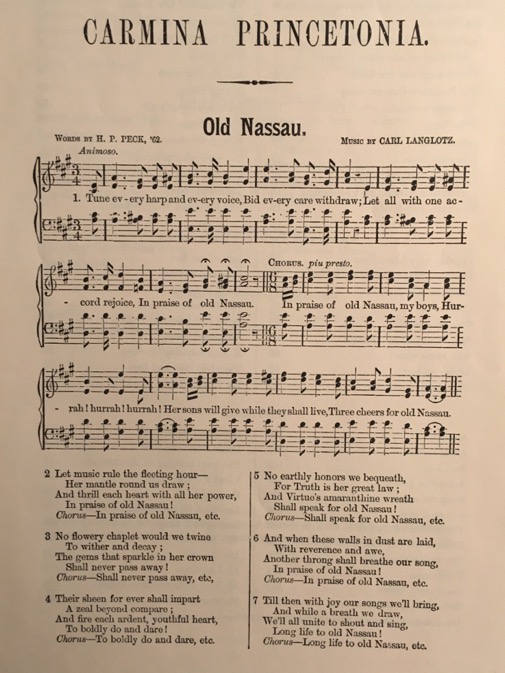

Contrary to appearances looking at the original sheet music, there are three (not two) intertwined but wildly divergent stories lurking behind the song. To begin at the beginning, The Nassau Lit decided in 1859 that the hodgepodge of college songs arising annually were not sufficient to the relatively new concept of school identity, and that the College of New Jersey needed a formal anthem. Few of the submissions explicitly mentioned Princeton for the glaring reason that it wasn’t the school’s name (and wouldn’t be for another 37 years). But try writing an “Ode to Dear New Jersey” sometime.

The first player in our piece is freshman Harlan Page Peck 1862, who was filling central New Jersey with poetry just as the call went out, already writing feverishly for The Nassau Rake (and seemingly anybody else who stopped by his room). This continued unabated until his graduation, when he composed the Class of 1862 Class Day Ode and its class “Cannon Song” — there was then a new one each year — and then migrated to the Princeton Seminary, possibly to find a calling wherein a poet could avoid starvation. His winning composition, “Old Nassau,” was to be sung to “Auld Lang Syne” (as was his “Cannon Song,” possibly betraying a somewhat narrow melodic repertoire), perhaps to appeal to the devout Presbyterians, and it laid out in seven glowing verses the image of an entire lifetime of loyalty to alma mater … and beyond.

And when these walls in dust are laid,

With reverence and awe,

Another throng shall breath our song,

In praise of old Nassau!

The second principal is just whom you’d suspect from the byline, Professor Karl Langlotz. A native of Germany and son of a musician, he studied with Liszt for a brief time, then emigrated to the United States at 19 to outrun the Prussian draft board. At 22, he ended up in Princeton with his young wife and by osmosis worked his way into the college community, first as a fencing coach in an era where college sports were unheard of, and then as a German instructor, chapel organist, and conductor of a small forerunner of the Glee Club, the Nassau Männerchor. In the modest college of John Maclean Jr. 1816, he prospered and was warmly regarded by all. Especially when hoisting a tall one down on William Street.

Which brings us to our third crucial character, William Christie Stitt 1856, a student at the Seminary and tutor at the College who was a few months older than Langlotz. Tellingly, he had been editor of The Lit as an undergrad, had written his class ode, and dabbled in all things musical. Stitt and Langlotz frequented a group that periodically met on William Street to sing college songs (really?) and drink beer (really!). When “Old Nassau” won the anthem contest, the group gave it a shot and decided the tune was a dreadful failure. Why? I’m not sure. Even when the Class of ’93 sings “Old Nassau” to the theme from Gilligan’s Island, I love it. But Stitt turned to Langlotz and insisted he write new music for the worthy song. Langlotz, assuming it would be forgotten when the sun rose again, readily agreed and forgot all about it. But Stitt, truly on the rah-rah bandwagon, proceeded to make Langlotz’s life a living purgatory, pestering him about the “commission.” Eventually, Stitt caught him unannounced one morning on his Mercer Street front porch and proceeded to stand over Langlotz as he wrote the entire melody in one sitting. Stitt then took the music and left. Though his music was adopted as the preferred tune for the alma mater, no one ever told Langlotz or showed him the sheet music while he was in Princeton.

Stitt received his Seminary degree and his master’s from the College in 1859. He left for a Civil War chaplaincy and a succession of Eastern churches until 1888, when he found his life’s calling ministering to seamen as secretary of the American Seamen’s Friend Society, which for 150 years strove to make shipboard life tolerable for sailors. He died suddenly in 1904, and was movingly eulogized as having “native shrewdness … allied to long experience.” Just ask Langlotz.

Peck, in turn, completed his Seminary training in 1865 and embarked on a ministerial career along with his young family that began in Beaver Dam, Wisc., but went sideways, to rural Illinois and Lincoln, Neb., which then had about 5,000 people. In 1875 his family stayed in Lincoln as he mysteriously left for Oregon, where he promptly disappeared forever, presumed drowned on an 1879 shipwreck in an unknown place. Until, that is, he showed up at his burial in überremote Milton-Freewater, Ore., in 1903.

When in 1868 the College brought the Rev. Dr. James McCosh in from Scotland to revive the place after the Civil War, he brought in European rock star Gen. Joseph Kargé to teach modern languages, and after 12 years the 34-year-old Langlotz was out on his well-tuned ear. He enrolled at the Seminary, then moved to Trenton where the music students were more plentiful, and where in 1869 he finally saw the authoritative version of “Old Nassau” with his attributed music in the first edition of Princeton’s songbook, Carmina Princetonia; he was dumbfounded. Living increasingly hand-to-mouth, he remained in Trenton, and was unknown to the University community until William Seymour Conrow 1901, a wholesale paper manager and frustrated artist and musician, rediscovered him in 1905. Conrow created a luxurious collectors’ edition of “Old Nassau,” including Langlotz’s autobiography. The alumni enthusiastically came to Langlotz’s aid, and he lived a comfortable semiretirement until his death at 80 in 1914. The episode motivated Conrow to quit his job and join the artists’ community in Paris. His portraits now hang in galleries across the Eastern United States.

When I sing “Old Nassau” at Reunions these days, I often think of the three trained ministers who wrote a truly great drinking song. The lonely poet Peck perishing in the wilds of Oregon; Stitt’s restless seamen relying on him for some small anchor of substance; and Langlotz toiling in obscurity beneath the dreams of Liszt. We all have classmates who are doing the same, and I’m not at all sure we remember them when we should. The cheery, well-off friends who can easily afford Reunions and the travel back each year aren’t the ones who really need to bid every care withdraw; the classmates with family problems and money problems and health problems and self-doubts — they are.

Your summer assignment this year is to find a classmate you haven’t spoken to in 10 or 20 or 40 years, who you know is far from the top of the world, and talk to them. Maybe about Reunions next year (most classes have scholarships for classmates and families who need it), maybe about meeting for coffee, maybe about art classes in Paris, maybe about “Old Nassau.”

3 Responses

Ellis P. Waller ’59

6 Years AgoBagpipers, Take Notice

Reading the Reunions issue of PAW reminded me of the little-known fact that it was I who transposed the music for "Old Nassau," "Going Back to Nassau Hall," and "The Princeton Cannon Song" into music for the Great Highland Bagpipes. This was done for the York (PA) Kiltie Band, which was hired to lead the Class of 1959 in the P-rade. I played with the band at our 55th reunion but was unable to make it this year.

I would be pleased to send the music to any Princeton pipers. I also donated copies to the music section of Mudd Library.

Rocky Semmes ’79

6 Years AgoAnother Musical Story

Ellis Waller '59 rises above the call of duty through his musical contribution for an arcane instrument in service of the "Best Old Place of All." Continuing good-naturedly here among family, in that spirit of transcription is a joke regarding a totally and entirely unrelated instrument told to me during a recent visit to Liberty Bellows in Philadelphia. Liberty Bellows is the internationally acclaimed accordion shop of founder and proprietor Mike Bulboff '02.

It seems an accordion player inadvertently left two of her most treasured accordions in the front seat of her car one day while visiting a shopping center. She had neglected to remove them the prior evening following a late-night gig. The next day, inadvisably she left the car in the parking lot unlocked.

When she got back to the car she found her two accordions, untouched, and an additional five more stuffed into the back seat.

There is no correlation whatsoever between Mr. Waller's rightfully respected bagpipes and the story here of Mr. Bulboff's also rightfully-respected accordions.

Paul Basile ’70

6 Years AgoCare for Those With Cares

“Bid Every Care Withdraw,” Gregg Lange ’70’s column posted July 3 at PAW Online, is playful and poignant, just like Gregg himself.

People expect that the clever, privileged, well-blessed individuals accepted to Princeton and other Ivies routinely become board-certified thoracic surgeons or intellectual-property lawyers, and many do — though it’s never automatic and seldom easy, even with palpable advantages. And for those with less visibly traditional success, life can at times seem the vehicle for bringing unbidden cares, frustrations, and setbacks.

Reunions are times for celebration and for remembering ... and for caring. A time to care for those with cares — who, I expect, represent a larger proportion of “Old Nassau” singers than we might think.