Rally ’Round the Cannon: Checking Under the Hood

When we look at modern man, we have to face the fact that modern man suffers from a kind of poverty of the spirit which stands in glaring contrast with a scientific and technological abundance.

— Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

As the national government gleefully begins to consider rewriting history, it’s a pretty good time to discuss some episodes that certainly must be on the chopping block, since they involve slavery, civil rights, white vigilantism, and a plethora of lies, in turn, about prior eras of American history and revisionism.

Let’s blame Johns Hopkins for it.

Opened in 1876 thanks to the unprecedented donation of its namesake founder, Johns Hopkins was structured as the first American research university on the German model, emphasizing graduate studies. Only seven years later, the Hopkins political science department welcomed two young and very bright lads preparing to decide what they wanted to be in life, as young lads will do. One was Thomas Woodrow Wilson 1879 of Virginia, veteran of the Whig Society, Princeton baseball and football staffs, and chair of The Daily Princetonian. He was already a lawyer, having learned enough to know he detested the practice of law. He was enrolled in the Ph.D. program, with an eye toward studies of American government and perhaps teaching. The other was Thomas Dixon Jr. of North Carolina, recent highly decorated graduate of ultra-Baptist Wake Forest, who as a result had earned a scholarship to Hopkins. According to Dixon, he and Wilson were intimate friends — they certainly did know each other. They were only there together one semester, with Dixon deciding he wanted something glitzier than academics; he headed to New York to try acting and journalism. By 1885, Wilson had his degree and was teaching at Bryn Mawr, and Dixon was back in Carolina … with a law degree, mulling over politics.

On their way to a destiny of sorts, Dixon exhibited a restlessness, abandoning the legislature and the law for the ministry, then abandoning the ministry after stints in North Carolina, Boston (where he was shocked to find racism), and New York to go on tour as a public intellectual, lecturing on the plight of the common man and the evils of Reconstruction in the South (his father and uncle had both been active in the 1860s Ku Klux Klan). Famed for his erudition, he became wealthy, which if anything drove his restlessness further. Outraged after seeing a stage production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, he channeled his anger over its view of the South into a new avocation: He wrote his first novel. Actually, he started with a trilogy excoriating Reconstruction and painting white Southerners as its victims. The second volume, The Clansman (1905), romanticized the old KKK and sold in the hundreds of thousands for Doubleday. His many books, unreadably turgid today, piled with racism, fear of Black people and socialists, and whacko genetic ideas, made him richer still. This coincided, unhappily, with the birth of the feature motion picture.

As you, the Experienced Historian, are already well-versed in Woodrow world, we will just note that, in the same time span, Wilson joined the Princeton faculty, became a renowned historian, teacher of law, public orator, headliner of Princeton’s Sesquicentennial, then president of the University in 1902. When Dixon was publishing The Clansman in 1905, Wilson was hiring 50 new preceptors, pushing Princeton toward the Oxbridge teaching model and away from the Hopkins German approach he hated.

The next 10 years were a blur for both. Dixon churned out novels and turned them into plays, with movie folks (always looking for content) at his heels. Wilson lost his big Graduate College fight to Andrew Fleming West 1874, then went on to be New Jersey governor in 1910 and U.S. president in 1912. While expanding the federal government by day and resegregating it at night, Wilson was active in everything from tariffs and taxes to the Federal Reserve Board to White House entertainment (ring a bell?). After screening Giovanni Pastrone’s epic historical movie Cabiria for guests on the White House lawn in 1914, he moved the projector uptown to the East Room on Feb. 18, 1915.

Thus were the two Southern Hopkins acquaintances destined to meet again.

Set during the Civil War and Reconstruction, The Birth of a Nation — which had been released to sensational reaction 10 days earlier — was D.W. Griffith’s cinematic response to Cabiria and the first huge American epic ever made. An adaptation of The Clansman, it simplistically portrayed Northerners and carpetbaggers — and virtually any Black person — as evil, and white Southerners as victimized, desperately defending their rights through such creations as the KKK. But the technical visuals and overall production — it was the first film with a full music score — were so overwhelmingly impactful that the picture was a sensation wherever it was shown (it was banned in Chicago, Detroit, Ohio, and other places as being a potential cause of racial unrest). Dixon talked Wilson into screening it at the White House, then gleefully joined the overheated PR campaign that followed, creating false quotes of approval from the screening. Wilson said nothing directly, implying … very little. The film was a box office sensation, the highest grossing in the world by far until Gone With the Wind in 1939.

And so Wilson, Dixon, and Griffith managed to pull off one of the more stupid cultural blights in American history. After 40 years on the trash pile, they revived the Ku Klux Klan, this time nationally as opposed to mired in the South. To lay the blame directly on the movie is not a stretch; such klan hallmarks as the white robes and cross burnings were created by Dixon, not ingredients of the original 19th-century klan. It then neatly dovetailed with Jim Crow, rabid anti-immigrant sentiment, Prohibition (which had blatant ethnic overtones), eugenics, and white nationalism to inflame racial issues in the country that only began meaningfully to abate in the 1950s.

How did this affect Princeton? To be honest, the answer is “oddly,” given that it would still admit no Black students at all, and began secret quotas to limit Jewish admission in the early 1920s.

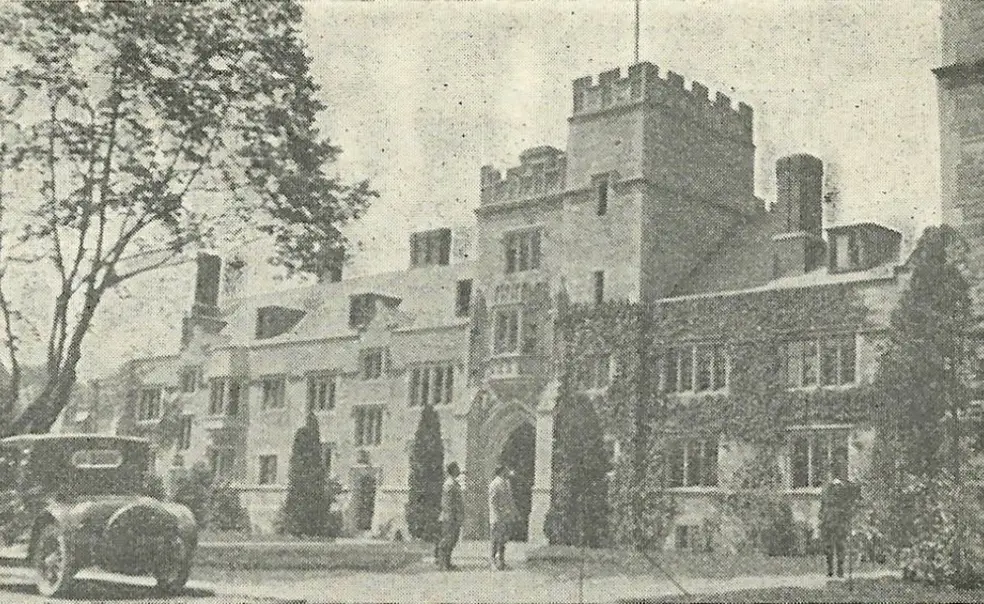

It began with the strange Alma Bridwell White, founder and self-styled bishop of the Pillar of Fire Church, which established a home base just north of Princeton in Zarephath, New Jersey. A feminist, she could otherwise have been mistaken for Dixon; when she established Alma White College in 1921, with her son Arthur Kent White *1921 as president, the curriculum instantly brought the klan to mind. The national KKK formally invested in the college in 1923 as its popularity crested. The Daily Princetonian got wind of this, sent a reporter to talk with Bishop Alma, and came back with three pages of vituperation, including implicit threats to Princeton if it didn’t get on the racist bandwagon. Next to it ran an editorial excoriating the klan and its ideas, not to mention its cowardice. This led President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 to portray the klan as lawless vigilantes and (somewhat ironically) denounce racism. In a Reformation Day message at the Chapel, admired “preceptor guy,” professor, and crew coach Duncan Spaeth warned that appeals to imaginary history “must not lead us to countenance movements, like the Ku Klux Klan, which revive religious animosity and disintegrate rather than unite the nation” in a return to medieval mentality. The Class of 1920, in sympathy with that, chose to lampoon the klan by wearing “nightshirts” with anti-klan signs at 1924 Reunions, but the image was so strong it was uncomfortably failed humor on a morbid scale.

On Oct. 16, 1924, the klan held a rally on the road to Trenton, about three miles from Princeton, then the local members elected to drive through town in hoods to be obnoxious. Eight hundred students poured onto Nassau Street, completely stalled the impromptu procession, started disrobing the various Kleagles, and the local police needed to come save the vigilantes. Paul Swain Havens 1925, soon to become a Rhodes scholar, publicly noted “as instinctively as a dog growls at a thief in the night, so that crowd growled at the Ku Klux Klan.” Ideology aside, the vigilantism of the klan just had no discernable appeal (or less) at Princeton. For a short period, that wasn’t true in much of the country, but the Alma Whites and their allies repeatedly overplayed their hands, and klan membership plunged from millions to perhaps 30,000 in 1930. And thankfully (First Amendment or not), no one ever made another Birth of a Nation.

No responses yet