Rally ’Round the Cannon: Ghosts of Princeton Past

‘Let’s go to Palmer Stadium and relive the crowds and the thrills and the closeness of Princeton.’

The bell clangs eight! Our voices cease,

And twilight charm gives way to night.

The once thronged campus, now in peace,

Lies dark and empty in our sight.

— The Steps Song, Ernest Carter 1888, 1894

The year 2020 was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. Old 2020 was as dead as a doornail.

Normally that would mean the campus had emptied. But not this time, for it had been empty long since — enveloped in gloom and disease and lost chances. I ate a melancholy take-out meal from the most melancholy tavern I could find and went to bed, knowing my usual seasonal visit was in store. Sure enough, at the stroke of midnight I was beset by the Spirit of Princeton Past, demanding to ruin a perfectly fine year-end slumber. I was ready this time, and implored, “Look, this year has been the pits. You always show me interesting old Princetoniana, but it’s often dark, with loneliness and graves and stuff. Just give me a break for once.”

“Fair enough,” it responded. “Name any campus structure from your lifetime, now gone, and that’s where we shall go.” Caught off guard, I tried to play offense — where might be the cheeriest spot, now vanished? The old tennis courts where Bob Goheen ’40 *48 and Bill Bowen *58 first met face-to-face? Reunion Hall, John F. Kennedy ’39’s freshman dorm? Class of 1941 Hall, my freshman dorm (although perhaps not; there was the dry ice incident…)? And suddenly it hit me.

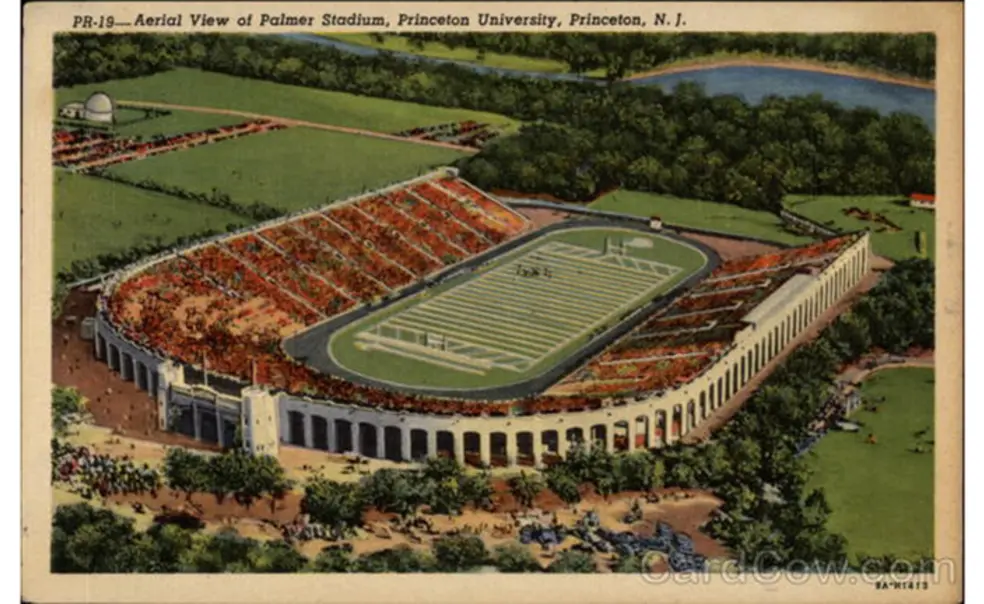

“Let’s go to Palmer Stadium,” I blurted out, “and relive the crowds and the thrills and the closeness of Princeton.” The Spirit, whom I always suspected of being a quantum physicist gone somehow askew, seemed to contemplate for a nanosecond, and then assented. “Once as the Nassau Hall bell tolls one, once at two, and again at three.”

“Couldn’t I take ’em all at once, and have it over?” I groused. But 10 seconds later I was out like a light.

Then came the toll of one, when the Spirit grabbed me by the scruff of the neck (familiarity breeds contempt, I suspect) and we whirled into Palmer Stadium. Maybe 6,000 people dressed like extras from a ’30s gangster film screamed madly as two runners pulled away from a very fast field in a distance race on the cinder track. I realized I had specified nothing regarding past events, just the stadium itself. Duh. As the gun went off to signal the final lap, a burly Princetonian with jet-black hair was leading a lithe, gliding runner in an Oxford singlet by a couple yards. They dueled down the backstretch toward the frantic crowd, then the Brit forged ahead with 100 yards left and slowed, spent, at the last second. But the Tiger couldn’t overtake him, and as the place went berserk, it was announced that both had broken the world record for the mile, with Jack Lovelock (a New Zealander, actually) running 4:07.6, his best ever by over four seconds, and rising senior Bill Bonthron ’34 running 4:08.7, a half second faster than the existing world record, and a new American record by far. I already knew The New York Times the next day (July 14, 1933) would call it the greatest mile race ever run. I knew by 1937 the six fastest miles ever would have been run on the great cinder oval at Palmer. I also knew Bonthron would astonishingly come back 90 minutes later to win the 880 over a world-class field in 1:53 to clinch the meet, but of course the Spirit wouldn’t let me stay. It wanted me to see a Princetonian break a major world record in Palmer Stadium — and lose. Sadist. I fogged out.

At the toll of two, we were back in Palmer. Before just a smattering of spectators, a fairly disjointed Princeton/Penn track meet — is there another type? — was lurching in fits and starts. There was a new composition track laid in place of the old cinders, and the press box had changed dramatically. The athletes were wearing bright synthetic fabrics, and the fold-out program read April 1, 1990, seven years before the stadium’s demise. The runners in another distance race were already beginning to separate on the backstretch, the rabbits for both squads falling back. The final lap was highly competitive, with two excellent Penn runners and a Tiger separating themselves and the latter nipping his way into second place at the finish. As I complained to the Spirit that the genie from Aladdin would have done a far more compelling job of wish-fulfillment, we drifted over to the clot of Princeton finishers after the 5,000-meter race, with one of the close-but-no-cigar ones clapping the second-place point-scorer on the back. The wiry clapper was alarmingly slight, maybe 125 pounds, with long, almost translucent hair. As he looked at me for an instant, I realized he was Alexi Indris-Santana ’93, or more precisely wasn’t Alexi Indris-Santana ’93, since in reality there was none. I was looking at perhaps the greatest Princeton con artist of the 20th century (which is saying something) at the only outdoor home track meet he ever ran. “C’mon, dude,” I groused wraithward, “maybe I forgot to mention Pepper Constable ’36 or Dick Kazmaier ’52 or Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 or whomever, but this has become cruel.” I swear the Spirit was cackling a little as I blanked yet again.

And so it tolled three. “Gotcha covered,” said Spooky, “here’s a great crowd of 35,000 for you. No whining.” It was halftime on the noisy football field, with the Tigers and Yale tied at 7, and in a flash I realized the Spirit had brought me to my own past for the first time ever. It was Nov. 15, 1969, and while many Princeton students were here, a thousand or so were at the March on Washington demonstrating against the Vietnam War, thinning out the normally rabid student section. Both bands marched together, carefully coordinating into a huge peace sign on the field, and the tenor of the crowd changed. The announcer acknowledged those marching in Washington, and as they unfurled a banner reading, “Make peace, not politics,” the bands played the Navy Hymn:

Eternal Father, strong to save, whose arm doth bind the restless wave,

who bids the mighty oceans deep their own appointed limits keep:

Oh, hear us when we cry to thee for those in peril on the sea!

A large number of the alumni on both sidelines were booing. For the second time, I was in tears. The Spirit, of course, said bupkis. Then it all vanished.

I was irate for days. This sort of grating torture I surely did not need, especially in 2020. But I now grudgingly suspect method in the Spirit’s snarky madness, and even a message. No matter how much we hope and try for respite, and perhaps even deserve it, sometimes we still find only mixed blessings, or melancholy, or embarrassment, or even downright antagonism. We have surely been together in peril on the sea. It still must not quench our desire for, or concerted attempts to find, peace for ourselves and all of our sisters and brothers. Perhaps — but alas, only perhaps — it’s now at last the time.

God bless us, every one.

4 Responses

John H. Hedeman ’72

5 Years AgoPalmer Stadium Lives in Lawrence, Kansas

Gregg, I have been avid reader of your accounts in the PAW for some time. Recently, you have been much on my mind because I am co-authoring an account of WPRB with Owen Curtis ’72 for our class 50th reunion book. My conversations with Bruce Elwell ’72 have been peppered with references to you.

Regarding your visit to Palmer Stadium, I have the good fortune to see a legacy of Palmer Stadium on the campus of the University of Kansas. Palmer Stadium was the inspiration for the design of KU’s Memorial Stadium (now David Booth Memorial Stadium). I think of great memories of Palmer Stadium every time I walk or drive by the KU stadium, which is located very close to my wife's (Anne D. Northup ’74) office.

Richard Seitz ’75

5 Years AgoGregg Lange’s Christmas Present of the Past Delights

As always, Gregg Lange ’70 brings delights from the past, and, never more welcome, ends this rotten year with something to make us smile.

From Dickens: It’s good to be Children sometimes & never better than at Christmas when its mighty creator was a Child Himself.

Thanks for the present, past, and future, Gregg.

George Bustin ’70

5 Years AgoA Gem for the Christmas Season

Beautifully written, evocative of Princeton memories, perfect for the season. Dr. Lange, you are a pleasure to read.

Richard Wakeford *88

5 Years AgoMemories of Princeton

I enjoyed this piece and never knew about the world record sprinting. One of the members of our class, an American, said that it was essential to learn something about American football. As a Brit, a visiting mid-career student, I welcomed the opportunity to view it live — with family members too. The game seemed hard to follow — but then so does our cricket and various forms of rugby; and our football is completely unlike that in the U.S. Your article took me back to 1987-88 and the generous welcome so many Americans offered our family over the course of an amazing year.