"Well shut them books and throw ’em away

And say goodbye to dull school days

Look alive and change your ways

It’s summertime ...

It’s summertime, summertime, sum, sum, summertime …"

– Sherm Feller and Tom Jameson

This year, falling prey to the perverse human tendency to ignore the great wisdom of the past, I failed to take the Jamies’ sage advice, poignantly noted above. Fortunately the risk paid off, especially for those of us who like game theory.

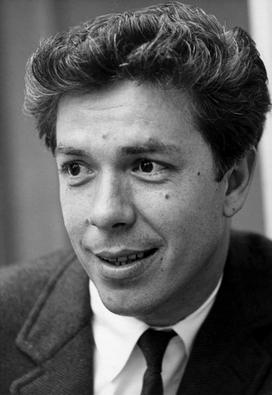

I had for some months been prearranging a pair of oral-history interviews with professor emeritus Harold Kuhn *50, and the mutual scheduling had dragged past Reunions and Commencement into June, so at long last I took my trusty notebook and audio recorders — the Princetoniana Committee makes a habit of double-recording everything so a technical glitch doesn’t result in the volunteer interviewer and the subject becoming sobbing lunatics — and hopped NJ Transit into the Big Apple.

Professor Kuhn is highly honored in academic circles for a number of achievements. He came to the graduate school in the ’40s along with such luminaries as John Nash *50 and David Gale *49, and along with them and their professor Albert Tucker *32, took the seminal ideas of game theory, the recent creation of Institute for Advanced Study mathematician John von Neumann and Princeton economist Oskar Morgenstern, and expanded it into one of the great practical intellectual advances of the century. In 1950, Nash submitted to Tucker the dissertation on n-person games that later would win him a Nobel Prize in economics. Kuhn and Tucker in 1951 described what became known as the Kuhn-Tucker conditions for nonlinear programming, now an economics staple. As a postdoc in 1952, Kuhn taught Princeton’s first game-theory course. In 1955 he published the Hungarian Method, an algorithm in combinatorial optimization (but hey, you knew that), subsequently named the best paper in 50 years of the Naval Research Logistics journal, which named its annual prize for him. To accomplish this, he had to teach himself Hungarian, the sole language of the two crucial papers in the field. Subsequently honored multiple times in Hungary for the achievement, he discovered much later that officials there assumed he was of Hungarian extraction, because nobody else possibly could have mastered the language.

When he returned to Princeton to teach in 1959, Kuhn was hired jointly by the math and economics departments – a prescient move, considering that even the crucial “prisoner’s dilemma,” one of the hallmarks of economic negotiation, had been named only nine years earlier by Tucker, coincident with Nash’s seminal paper and its “Nash equilibrium.” Remaining in both departments for his ensuing career, Kuhn taught essentially everything, from price theory to managerial economics, microeconomics and mathematical economics to trade theory, game theory, and linear and nonlinear programming. He actually drew 90 students for his elective 300-level course in mathematical programming, and was adviser for piles of senior theses in both departments. His popularity eventually came home to roost: Two of his students (Dick Quandt ’52 and Alan Blinder ’67) eventually became his chairman in the economics department. He, Gale, Tucker, and Nash appropriately were awarded the von Neumann Theory Prize in operations research. He began a campaign in the 1980s to get his friend Nash a Nobel Prize in economics against daunting odds – Nash’s long-standing schizophrenia as well as the legendary bias of the committee against applied economists. Nash’s eventual triumph in 1994 earned Kuhn a trip to Stockholm, a prominent spot in Sylvia Nasar’s Nash biography A Beautiful Mind, and a technical adviser’s credit on the ensuing movie, as well as being co-editor of Nash’s papers with Nasar. For 20 years, he’s been a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

And while all of that is fascinating and the subject of my first interview with Professor Kuhn, it isn’t why I bring him up here. That was just his day job.

In 1967, Harold Kuhn was elected to a faculty committee working on a first-time written code of conduct for students (you may wonder why they were doing this – stay tuned); he didn’t much like the state he found it in, sort of in loco parentis on steroids, and set about to create a new approach to the incorporation of undergrads as citizens of the University. The immediate result was the initial version of Students and the University, now the focal part of Rights, Rules, Responsibilities, the behavior guidelines for the entire University that have been in place, with some tweaks, ever since. The faculty approved it in the spring of 1968; given the broad-ranging structural issues it raised and the sense within the faculty that it was exercising far too broad authority for its own good, at their very next meeting they created the Kelley Committee, to review and recommend Universitywide governance changes to the trustees. Kuhn was on that committee of 15, along with students, President Bob Goheen ’40 *48, and other notable faculty like engineering’s David Billington ’50 and sociology’s Suzanne Keller, Princeton’s first tenured woman. As the resident instant authority on student discipline and rights, Kuhn did the heavy lifting on that section of the new structure, which also created the unprecedented CPUC as the pan-University advisory council to the trustees, a structure that has served as a propellant of the growth of the University’s breadth and depth over the last 40 years. In a classic case of no good deed going unpunished, Kuhn became the first chairman of the CPUC Committee on Rights and Rules when it was formed, and so had to negotiate the shoals of the 1970 Hickel heckling incident that preceded Cambodia, Kent State, and the student strike. Having impressed Goheen in this role, he was asked to speak to the somewhat hostile and mostly clueless assembly at Alumni Day (an address that he adapted for PAW on May 5, 1970), which is as fine a general examination of academic governance as you’re likely to see, even today. This era was the topic of our second interview, and what I thought you should consider for a moment.

He didn’t have to do this. It took a lot of time. He got yelled at. His department heads didn’t care (unless they missed him at meetings and were miffed). It disrupted his research and business and home life. But even then, that’s not really the full point. I note this because it’s not remarkable at all at Princeton; the contributions of the faculty to the community beyond their teaching and research are persistent and astounding.

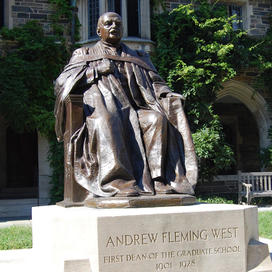

Professor John Maclean Jr. 1816 started the Alumni Association in 1826. German professor Karl Langlotz not only introduced fencing, but even composed the melody to “Old Nassau” in 1859. You probably know that Latin professor Andrew Fleming West 1874, later the first dean of the graduate school, was the chief organizer and fundraiser for the University’s big game-changing 150th-anniversary celebration in 1896, but did you know he started the Glee Club? History professor Buzzer Hall, possibly the most dominant Princeton teacher of the first half of the 20th century, ended up in a PAW photo canoeing with undergrads in Maine. Psychology professor Julian Jaynes was not only master-in-residence of the Woodrow Wilson Society in Wilcox Hall in 1967, but pitched the creation of Wilson College, including adjacent dorms, to Goheen and the trustees, establishing a new social structure on campus. At the same time, religion professor Malcolm Diamond, a Freedom Rider in the ’60s, served as the first master of Stevenson Hall, the other new University-sponsored social alternative. English professor emeritus John Fleming *63 has served on a batch of Alumni Council committees, and until his recent retirement may have been the best weekly columnist the Prince ever had. Sociology professor Marvin Bressler, unforgettable in his real job of teacher and 20-year department head, also chaired the groundbreaking Committee on Undergraduate Life in the ’70s and, thanks to a limitless fixation on basketball and Coach Pete Carril (admittedly a fine subject for a sociologist or two or three), became inseparable from the squad, and thus inspired the athletic department’s Academic-Athletic Fellows Program, now involving dozens of senior faculty.

They, and Jaynes’ many successors in the college-master ranks (English professor Jeff Nunokawa, for example), and Harold Kuhn and politics professor Stan Kelley’s faculty successors in the CPUC and committees on social life and women’s involvement, and on and on and on, are far more than volunteers: They are highly skilled, artful weavers of the Princeton community fabric – not just its business – and a priceless lesson to all of us who pass through as to what our own contributions in life can and should be. Dei sub numine viget.

Speaking of Princetoniana, it is with great sadness that I briefly note the death in August of Bob Rodgers ’56 h’81 h’06, an embodiment of the Princeton spirit in the best tradition of Fred Fox ’39 and Bud Wynne ’39. Seemingly involved in every corner of the campus keeping the University’s past fresh and fun, Bob was up to his blazer in ’56 Reunions, pocket Princetoniana libraries, collections of memorabilia (especially class jackets, which if you’ve ever tried to store a few dozen can really be an orange and black pain), the Pre-rade and freshman Step Sing, and ambassadorial functions to his honorary classmates in his offspring class of 1981 and grandchild class of 2006, just for starters. Chairman emeritus of the Princetoniana Committee, he invariably found the common ethos in alums, faculty, and staff of many generations, and melded them into a cheery force of good will and support for Princeton’s noblest efforts.

Along with his wonderful kindred spirit, Sue Rodgers s’56, and the rest of his class, I feel the great pain of his passing and the joy of having been his friend.

Click here to see video of Bob leading the Locomotive cheer at the 2011 Senior Step Sing.

No responses yet