“Believable fairy-stories must be intensely practical. You must have a map, no matter how rough. Otherwise you wander all over the place.”

— JRR Tolkien

It’s hard to tell, before you scratch the surface of people’s personal pasts, where their real flashpoints lie. We recently took a look at Princeton’s new planning document in the light of historical land acquisitions by the trustees, given their current plans for further expanding the campus across Lake Carnegie, adding two more residential colleges, that sort of thing. Big stuff, which is one reason the plan looks out beyond 10 years, the horizon for similar exercises in the recent past. A lot to digest, many fish to fry. Lots of moving parts, as we consultants used to say about complicated things before essentially everything became made up of binary code instead of actual parts.

For those alums who followed up with me, there seems to be an overwhelming candidate for Panic Leader, the planning trial balloon that generates the most consternation as the trusty old-timers survey the various threats to tradition (a fraught activity actually far more traditional than any other particular tradition).

The golf course. Springdale Golf Club’s lease apparently has an out whereby the University can reclaim the land for other use as early as 2022. I barely mentioned it in our column, other than to note the namesake Springdale farm acquisition in the early 20th century from which the course was carved. But apparently the 12-handicap crowd is aroused, and while I do not regard this “threat” to be inconsequential, I would think the fact the University could build or acquire a superior course in a nonce might dampen the concern.

Besides, the fate of Springdale didn’t change when the new plan came out, it was sealed when Andrew Fleming West 1874’s monumental Grad College was constructed on the far hill in 1913, complete with great timbered hall, organ, carillon, dean’s house, chamber of secrets (the DBar), you name it. Tolkien would be proud. All you have to do is look at a map.

Ah-hah! So we come to the crux of today’s thought experiment, in which we consider the ubiquitous role of maps in campus development, and how they color our perception of history as well as future aspirations.

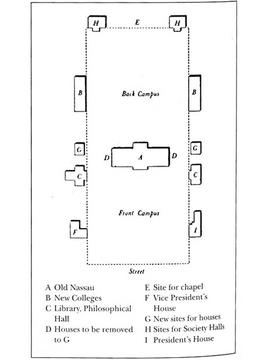

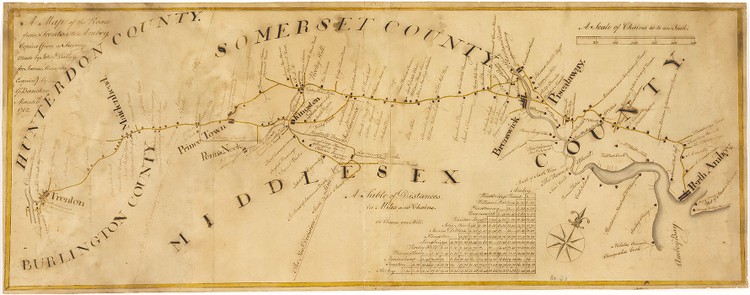

Our first stop gives us a chance to plug the Historic Map Collection at the library’s Rare Books and Special Collections division, which has documented its wonderful 2014 exhibition on New Jersey history, Nova Caesarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, in a fine digital exhibit. We’ll begin with a 1762 road map from Trenton to Perth Amboy, only six years after the College moved to Prince Town, which includes sufficient detail to show Nassau Hall on the highway above Stony Brook:

This precision is hardly surprising, given New Jersey’s pivotal location as a crossroads of the Colonies, and the importance became existential 15 years later when the Colonials found themselves at war with Great Britain.

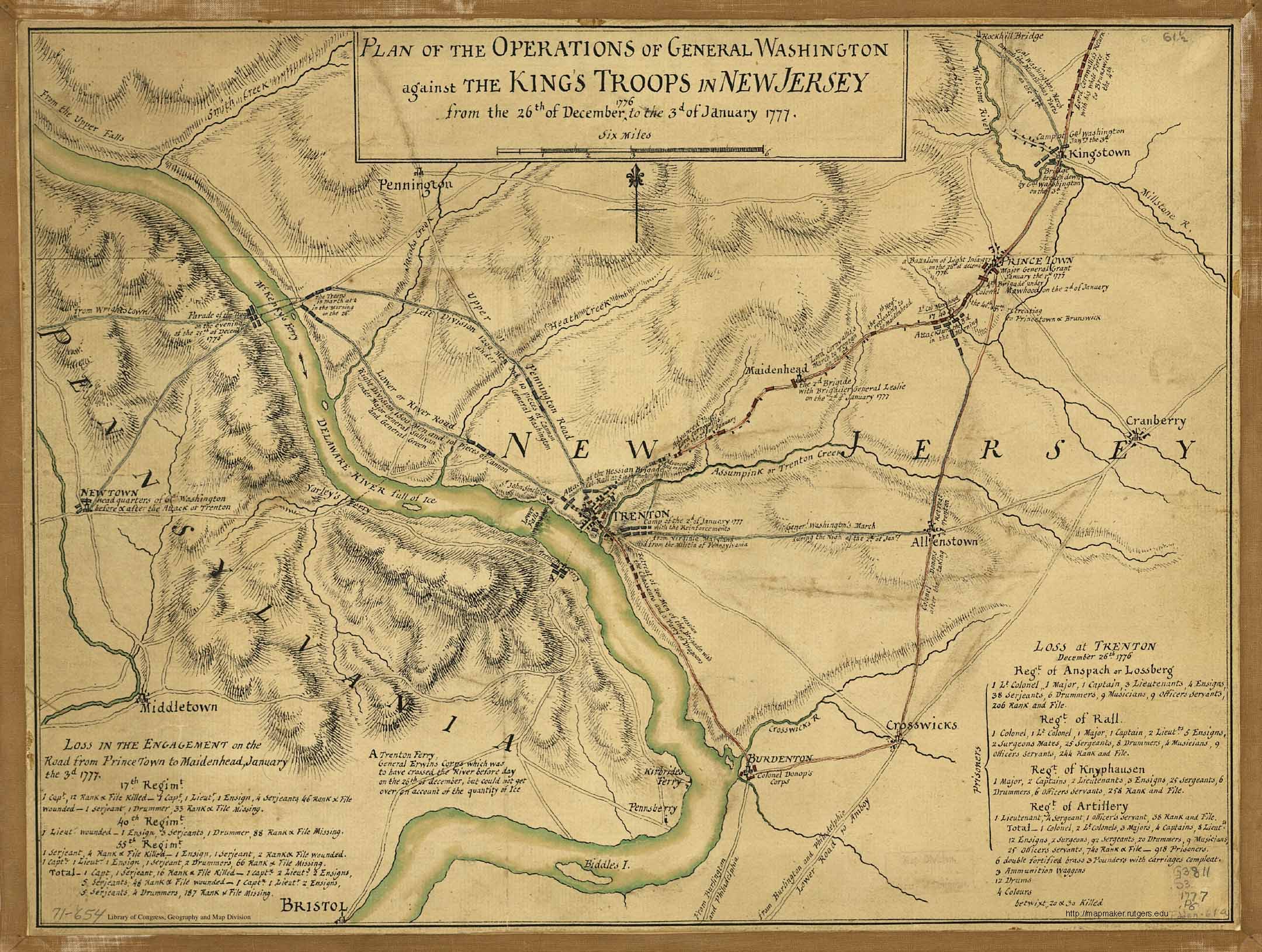

Consider a Revolutionary example: This map of the battles of Trenton, in December 1776, and Princeton, in January 1777, was researched, drawn, and published by the following April, again with excruciating detail to include key buildings, including Nassau Hall, and unit deployments. Why? As a military training vehicle, a propaganda weapon, and likely a diplomatic vehicle to raise funding and foreign support for the Revolution.

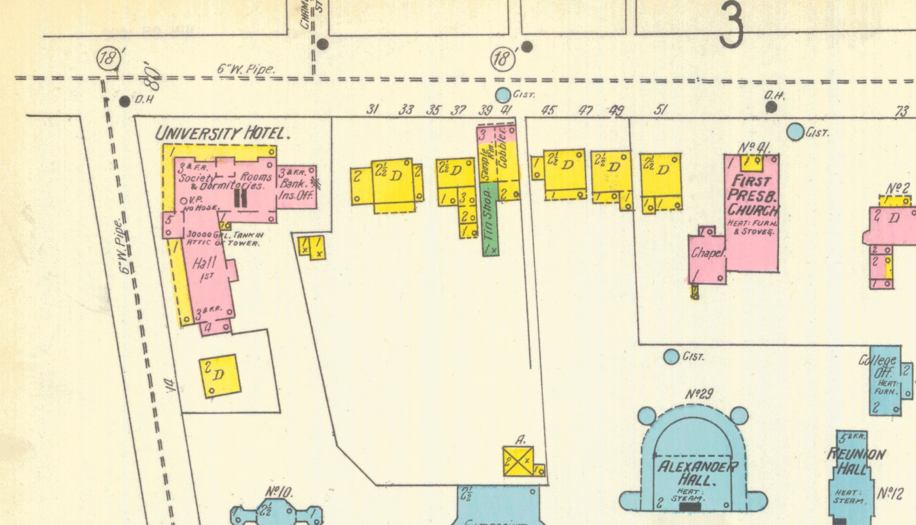

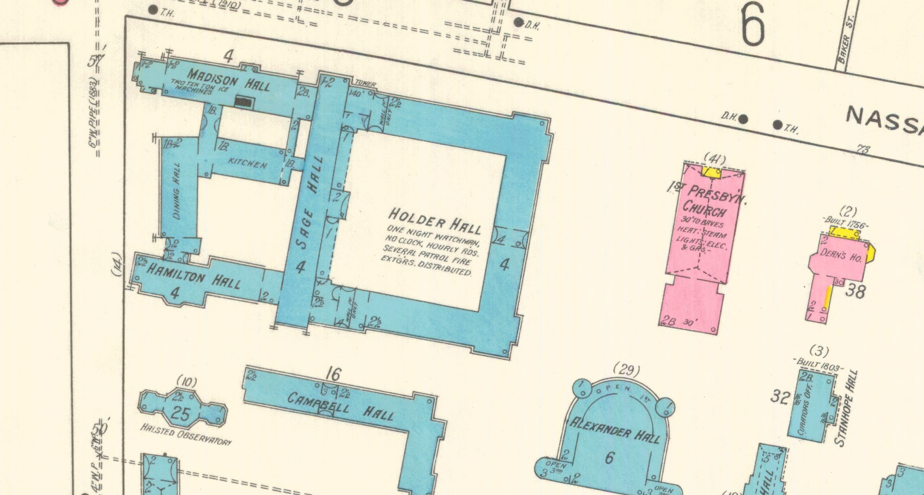

As the campus grew to match its own aspirations, the Borough of Princeton expanded in tandem and was documented by the Sanborn Map Co., first in the country to construct municipal and insurance maps beginning in 1866. One of Princeton’s most fascinating online collections consists of the Sanborn maps of a large number of New Jersey municipalities. The detail of every building unit is wonderful, and the resulting tracking of structural changes from map set to map set is endlessly intriguing. For example, here’s the southeast corner of Nassau Street and University Place in 1902:

And here’s the same corner 16 years later:

The first major attempt to marry an interactive map with campus history was, in fact, gigantic for its time and impressive still today. Underwritten by the University’s Bicenquinquagenary Celebration and created by the Education Technologies Center (now part of the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning), this 1996 leap into the infancy of the Internet era was grandly entitled Princeton University: An Interactive Campus History 1746—1996 and actually delivered on a large part of that promise. It had (well, technically still has) rudimentary 3D images of campus-scapes from various eras, with the ability to click through to information on a huge range of buildings, including those long gone. The narrative of the physical history of the University was the most thorough anyone had ever seen, and still contains morsels I’ve never encountered anyplace else outside the Archives (the 1834 Refectory?!). And the search capabilities, some of which no longer work because of platform obsolescence, are huge, multifarious, and include a bibliography of almost 300 works. But as with many gigantic leaps forward in information, it was unsustainable, and remains an impressive artifact rather than being dynamically updated. Still, play around with what’s there a little while, have a good time, and think about it; nothing really fills its role today.

Which is not to say there aren’t good online models from which to develop a new comprehensive interactive campus-history site that can be maintained in real time. There are actually three. The first, in order of complexity, is the no-nonsense interactive campus map that guides clueless seekers of Hoyt Lab or 1938 Hall, but is spotty on background information on most buildings. Then there’s one of my favorites, the Campus Art Princeton site, which shows off the magnificent outdoor sculpture collection of the Art Museum in a highly effective multimedia collection of descriptions, narrations, audio cuts, interviews, maps, and imagery that lets the user have a field day of discovery and appreciation of the campus through the artworks, even on her cellphone if she wishes. And third, there’s the impressive online Orange Key Tour, with gorgeous 360-degree photography of many iconographic campus locations. The current content is pointedly suited to applicants and their families. The map structure is a bit sketchy, but the platform is beautiful.

A full-blown Princeton campus-history site would not be cheap, either to construct or maintain. But the sheer amount and importance of our history that revolves around the campus itself demands it; for comparison, consider the new 10-year plan, which includes by my count 40 separate maps just to explain how to tweak things for 3.7 percent of the institution’s lifespan.

Well, there’s a Princetoniana Committee meeting in a couple weeks. I’ll run it up the Nassau Hall flagpole and see who strings me up next to it. Just ignore the jarring noises coming from Mercer County. Without a great map of where we’ve been, how would we really know where we want to go? Second star to the right, and straight on till morning.

1 Response

Douglas B. Rubin ’81

7 Years AgoThe Inconvenient 'Enclave' Within the University's Domain

If one looks at the most recent campus map

http://m.princeton.edu/map/campus

One might or might not notice a small patch of brown area along Prospect Avenue, amidst the green flow that stretches from the Graduate College past Harrison Street to the Butler Tract. Four (actually five) of the 16 historic eating club sites are now owned by the University.

If geography is destiny, what does this suggest?