“It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.”

— Harry S Truman

The year 1922 was an exceedingly busy time in the institutional history of Princeton. The campus had been thrown into high gear by the ideas and aspirations of the administration of Woodrow Wilson 1879 — not to mention the various expansive countermoves by Dean Andrew Fleming West 1884 and trustee Moses Taylor Pyne 1877 — but the University was then forced to pause for the difficulty of World War I and reconfigure afterward. The 1920 destruction by fire of the Marquand Chapel created an urgency for a new formal worship space among those aligned with John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893, the last of the reverend presidents. Studies were afoot for the new curriculum paradigm that became the Four Course Plan. The librarian was trying to figure out where to put and how to catalog all the new acquisitions the plan required. Concerns arose to limit numbers in the undergraduate student body, which in turn produced the admission office. Construction was beginning on the great new publicly subscribed Baker Rink. New tennis courts opened below Guyot Hall (more on that later). Three Gothic dorms were under construction simultaneously along University Place. And as the motor car took America by storm and the U.S. highway system began under the flashy President Warren G. Harding, concern was mounting over the safety of students on the roads.

So it would have been easy to overlook Mather Farm.

As the new automobile culture built up a head of exhaust, virtually everybody on campus certainly knew Mather Farm, but they didn’t know what it was, if you catch my meaning. In the same way the two generations prior had certainly known the Schenck Farm, and had been there dozens of times, but had no idea what that was, either. Each was an important piece of the Princeton environment, yet both were essentially below the conscious operating level of almost anybody. As you drove your 1922 Packard Twin Six south on Washington Road to Penns Neck, after you crossed Lake Carnegie the Mather Farm stretched on your right all the way to the Trenton-New Brunswick Turnpike, which in four years would become U.S. 1. In contrast, if you hopped on the Dinky at the new Princeton Station near the under-construction Pyne Hall and Baker Rink, your rail trip to Princeton Junction would take you through the middle of the Schenk Farm, from the D&R Canal all the way to the Pike in Penns Neck. The two farms abutted, and together occupied the 180 acres between Washington Road and Alexander Road, and between the Lake and the Pike.

As late as 1878, the southern extent of the campus had been, believe it or not, Whig and Clio; the entire grounds totaled 40 acres or so. The gift of Prospect and the surrounding Potter Farm then began extension outward, including notable chunks such as the Academy Lot that now holds McCosh and the Chapel; Springdale Farm, now the golf course and the Graduate College; boundary-defining Lake Carnegie itself in 1906; the Olden Farm on the east side of Washington Road all the way from the Engineering Quad to the Lake; Professor Guyot’s property and the adjacent Carpenter’s Hall, on which Rockefeller College sits; the Butler tract and Gray Farm on the corner of Harrison Street and the Lake; the new bequest from the late Moses Taylor Pyne 1877 of his Broadmead estate east of campus; and the old train yards at Blair Hall (and surrounding residential property), which allowed construction of the Gothic dorms leading behind the University Gym to that new train station.

By 1922, the approximately 700 acres of the University holdings (about a 1,700 percent increase in 44 years) extended along Nassau Street from University Place to Washington Road, on Prospect Street from Washington Road to Harrison Street, and along Stony Brook and the Lake from west of Alexander Road to east of Harrison Street. The hallmark of the large farm properties was their acquisition, almost always opportunistic by the trustees and based more on imagination than immediate need. While it gave them operational control of their own destiny, much of the boundary land to the south, east, and southwest was a convenient buffer, which allowed both the freedom to briskly expand when resources became available, and to do so with an attention to detail — landscape architect Beatrix Farrand comes readily to mind — that enhanced the reputation and sheer enjoyment of the grounds. Pyne himself had been the greatest exponent of this during his 37 years as a trustee, and his 1921 Broadmead gift completed the large expanses north of the Lake that essentially continue today.

So with only 2,000 students and hundreds of contiguous undeveloped acres, who at Princeton gave a tiger’s patoot about Mather Farm way across the Lake in 1922? It’s really funny that you, the Alert Historian, should ask because, well, uh … we don’t seem to know.

The U.S. economy was lousy, collections on pledged gifts were plodding, the trustees and Hibben had all that stuff on their plates, and I would bet they didn’t have any particular interest in agriculture. So those 180 additional acres don’t spring to mind as the Next Big Thing. There were, however, some “friends of the University” who thought otherwise, and they took the opportunity of the simultaneous availability of both the Mather and Schenck farms to dangle a deal in front of the trustees: They bought Mather, and if the trustees bought Schenck, they would donate Mather as a bonus. The offer was conveyed by trustee and formidable Philadelphia lawyer Bayard Henry 1876, who himself had previously purchased the land on University Place from Nassau Street to the new station and then donated it for the expanding Gothic campus. At the same January 1922 meeting it was offered, the trustees approved.

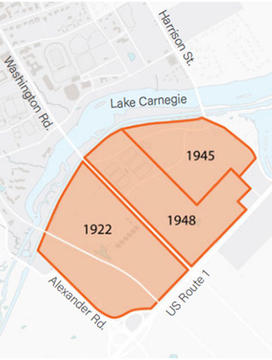

However, when the Jewell and Pullen farms on east side of Washington Road across from Mather and Schenck came on the market in the late 1940s, they complemented the 1922 acquisitions perfectly, and inevitably by 1948 the University owned 400 acres bounded by the Lake, Alexander Street, Route 1, and Harrison Street. The property, now known as the West Windsor Fields, is virtually the same size as the entire active central campus north of the Lake, and currently houses the rugby teams’ Rickerson Field and Haaga House, the cross country teams’ home course, and multiple other practice fields.

Now as much fun as this historical farm stand has been, and as much as we respect our “Give Blood: Play Rugby” brethren and sistren, who cares?

And even more intriguing, no one seems to know to this day who the “friends of the University” were who made the matching Mather offer. You might guess Bayard Henry to be one, but he had not been bashful about prior donations, so if he was one, there were clearly others. But any local wisdom beyond that seems nil. It’s certainly easy to imagine that without them, the West Windsor Fields as we know them wouldn’t exist, and University planning options for 2026 and beyond would be far more constrained.

We’ve discussed before the virtues and power of anonymous benevolence in people such as legendary trustees Dean Mathey 1912 and Jay Sherrerd ’52, but this is a case of modesty that is very hard to match both for magnitude of effect and longevity of vision. How about a 95-year-belated locomotive for “friends of the University”?

We devoted a couple columns to strategic planning when this cycle began three years ago (here and here), which may be helpful in coming to grips with the new plan, but if the vast range of it still starts to mess with your mind, let me suggest this: Focus on your favorite part (Engineering? Colleges? Wetlands?) for a few minutes, then think about it as your own little Mather Farm.

2 Responses

Jonathan Murphy ’57

7 Years AgoNot All of New Jersey

I sympathize with Norman Ravitch, but suggest he look a bit more carefully. Not all has been ruined. I live in an “adult development” just off Route 9 in Manalapan, N.J. (I use the address of Englishtown because it is easier to say, and is the same P.O.). Route 9 is mini-malls and major-malls, but as one gets away from the highways this area is rather unspoiled. I can drive to Princeton in about 40 minutes with most of my route being through farm country and old homes. I can take Route 9 south to Freehold and deviate to the Monmouth Battleground (or I can take back roads south to the Battleground, and pass the Presbyterian Church that was the Tennent Meeting House where Washington and his troops gathered before the battle).

The Monmouth Battleground is unique among our monuments, in a sense. It was preserved by a lack of interest. The farmland and forestland remained in family hands for centuries. The attempt at preservation only started about 40 years ago as the development only came to the area about then and it was unnecessary before then. Some of the woods are now apple and peach orchards, but that is change without spoilage. I drive down the Old Tennant Road when taking the back route to the malls (and my eye doctor, and Centra State Hospital, which I have to visit now and then). I pass the tiny church and giant church yard on the hill at Tennant (the graves are mainly pre-Revolutionary, and a a historical site). I turn left on the Freehold/Englishtown road and pass another churchyard of early post-Revolutionary times. I drive about three miles ESE, with old farm buildings and farmland or woods on each side, where I turn right an pass under a single track railroad bridge (the line built in the 1800s, not now used) and go SW by S through the orchards on each side on Wemrock Road. As I drive down Wemrock I'm passing through the passage where our troops made a badly planned attack on the English rear at Freehold, then retreated toward Englishtown/Tennant followed by the Brits, then the passage was reversed as Washington rallied the troops and set up enfilade cannon on the hill top to the side.

So when I drive to my eye doctor, or my radiologist, or take my lady to Walmart, I pass through miles of nearly virgin land where the “turn around” battle of our Revolution took place — and see no mini-malls on the way.

I don't disagree with Norm in general; I share his regret in the loss of our treasures in so many places. I just boast of the old families of Monmouth County over the years. They didn’t preserve the Battleground as a monument, they kept it as their farms. Luckily it is now official under state law, and the law is well written to keep the land in the hands of those who farm it, but with the stricture that should they sell they have to sell either to the Preservation Association or to others who will farm. A neat trick that avoids exploitation either as an “official park” or as a development.

I suggest that all Princetonians, should they be visiting the college and have spare time with a car, make a visit to Monmouth Battlefield. The drive, by “best route,” is about 45 minutes. I’ll not tell you the “nicest route” (which is also shortest), as it involves a lot of turns (but takes you through Cranbury Township, which is also pre-Revolutionary).

Take Washington Road out of Princeton and across the Route 1 circle. Just before the PJ&B station take the left onto the Princeton/Hightstown Road. It is obvious, it is a “zig” of the main road; Washington dead ends at the PJ station. Stay on the Hightstown road until you see the bypass, the road number is 133. That will lead you past the NJ Turnpike and other things to Route 33. Wow, if you think that is complicated you should see my personal route.

Your goal is Route 33 that runs from Hightstown to Freehold and on to the shore. Given that I'll offer one more diverging routing. You could aim for Old Tennant Presbyterian Church or for the Monmouth Battlefield. I’m getting tired and ready for bed, so I suggest Google Earth for the final pictures. Just zero in on Monmouth County N.J. and search the Church or the Battlefield and figure out your own final route. For those interested in real history, and preservation, the trip will be worth it. Unlike many monuments it is mainly in its original state — the small visitors center on the hill of the cannons is not intrusive.

Best,

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoThe Fall of New Jersey

I remember the beauties of New Jersey, including the Princeton area during and right after WWII, as I remember the beauties of Northern Virginia. Both areas, and I am sure countless others, have been destroyed by mini malls, housing, commerce, and the wrong kind of people in the wrong places. What a shame! But that is what they call progress. Progress! I remember walking the battle field of Manassas a few years ago in the summer heat and seeing mini malls and gas stations all around. Look at what Hightstown has become, near Princeton! Look around you and weep.