“History is merely a list of surprises. It can only prepare us to be surprised yet again.”

— Kurt Vonnegut

Here in the History Corner, you wouldn’t think there would be significant pressure to write about deadline topics or create a furor over what’s going on next weekend. The fall of 2018, however, was such a rare time. The football cognoscenti among us, having seen impending indicators two years prior in an Ivy League co-champion team, took a look at the promising roster led by John Lovett ’19, Jesper Horsted ’19, and a beautifully balanced defense, and as the squad got up and running — the average score over the first five games of the season was Princeton 52, Opponents 9 — the little nudges became overt: Could this be the year? The pre-hysteria started to build, and what became almost an expectation of a perfect season began to gather like a pendulous weight on the horizon.

When I guardedly opined that the lone thing I was willing to say publicly was that the Tigers’ last perfect season was 1964, and there were reasons for that, I met with malevolent indifference to my unwillingness to become the Harbinger of Historic Happiness (or the Prophet of Perfection if you prefer). Although I like to think I have some pretty fine friends out there, I’m not at all certain they wouldn’t have joined the entire Princeton Football Association in dismantling a fair portion of my anatomy had I forecast a 10-0 season that did not eventuate. I was perhaps 20 yards away from Lovett as he crossed the north goal line at Princeton Stadium with 6:33 remaining in the Dartmouth game to give the Tigers their first lead at 14-9 on Nov. 3; no one was happier than I, believe me, but if I had a publicized stake in the play, the happiness would have fallen to my next of kin.

And so we come to regression to the mean. While we fully recognize and celebrate the true greatness of last year’s team — rabid debate among Ivy old-timers seems to have settled on the idea it was likely the best Ivy squad since the 1970 Dartmouth team that won the Lambert Trophy — you must admit the chances of this year’s team surpassing it are slim. Meanwhile, the chances of falling back somewhat are well above 99 percent. There are, in fact, myriad ways in which this year’s team could cover itself in glory and still not measure up; among many other things, regression to the mean says they shouldn’t care. “Another op’nin’, another show,” in the words of Yalie Cole Porter.

Which actually leads to an idea to placate those remaining overenthused. Let’s take a look for our history excursus today not at the other perfect seasons sprinkled throughout the Tigers’ colorful 150-year gridiron history, but instead the season following each of them, to get a grip on what we should look for this year. To set reasonable parameters, we should start at the point Princeton followed the new trend to full-time football coaches in 1915. (The game, and even schedules, were quite different previously.)

The emotional Bill Roper, Class of 1902, who to this day has won more games than any football coach in Tiger history, got going after World War I and in 1922 led likely the best-named team in history, the Team of Destiny. The Tigers navigated multiple brushes with death and barely edged Harvard and Yale. And their transcendent game came on a huge stage — on the road at the University of Chicago against the great Amos Alonso Stagg’s juggernaut Maroons, with the national press draped over everyone. Chicago had the Tigers seemingly buried twice, but Princeton came from down 18-7 to win 21-18 and earn the nickname.

While 1922 was indeed a season of destiny, 1923 was not. Princeton overenthusiastically invited Knute Rockne and Notre Dame to Palmer Stadium, where they waxed Roper’s squad 27-2. A subsequent 5-0 upset by Harvard and 27-0 shellacking at Yale mercifully closed out the season at 3-3-1. Roper flirted with undefeated seasons in 1927 and 1928 but lost the closing game in each; after 1930 he was gone.

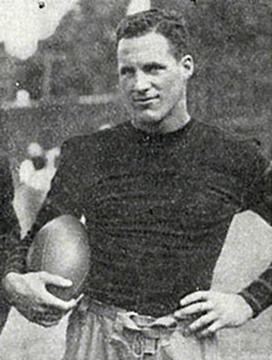

Princeton imported Fritz Crisler and his staff from Minnesota to shake things up, and in 1932 they did to a fare-thee-well; he both coached a miraculous 2-2-3 season (his first year), bouncing back from the dismal 1-7 1931 campaign with little talent outside all-everything captain Josh Billings ’33, and “recruited” — a very murky concept at the time — the stupendous Class of ’36. As sophomores, they were 9-0, outscored their opponents 217-8, destroyed Yale 27-2, and dominated Columbia (that year’s Rose Bowl winner) 20-0.

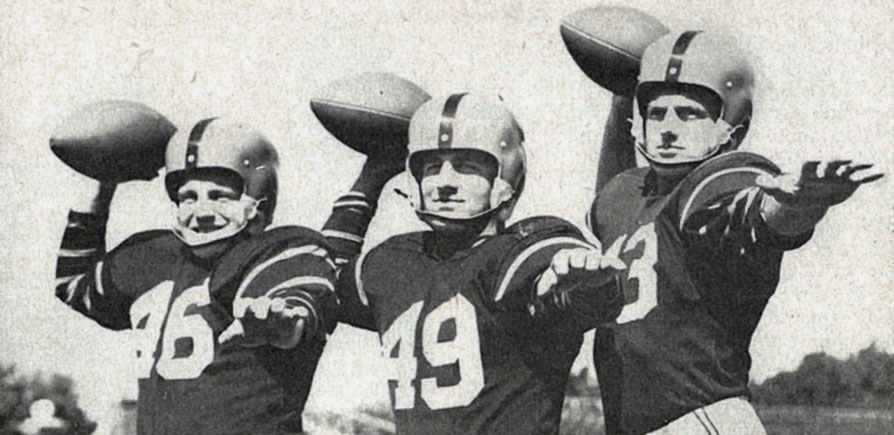

Dick Colman, Caldwell’s disciple and successor following his mentor’s death in 1957, coached the Tigers to an emotional Ivy championship that season. His Tigers tied Dartmouth for the Ivy title in 1963, and then in 1964, they put all the pieces together for an undefeated 9-0 season led by Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65, following Caldwell’s blueprint from 1951. This would be the last undefeated Tiger squad until the fall of 2018 (the 54-year interim was a bit longer than the previous longest hiatus between perfect seasons: 19 years between 1903 and 1922). But the wonderful 1965 team — with Paul Savidge ’66 defending, Ron Landeck ’66 throwing and running, and Charlie Gogolak ’66 kicking — made a great run at it, going 8-0 into the final game in which they were overrun by a deeper Dartmouth team, 28-14. The Class of ’66’s run of 24-3, one then matched by Walt Kozumbo’s Class of ’67, which went 7-2 the following season of 1966, was pretty spiffy; the best three-year stretch in the 21st century spans from 2016 to 2018: 23-7.

For statistics fans, a review:

| Undefeated Season | Record | Following Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 8-0 | 3-3-1 |

| 1933 | 9-0 | 7-1 |

| 1935 | 9-0 | 4-2-2 |

| 1950 | 9-0 | 9-0 |

| 1951 | 9-0 | 8-1 |

| 1964 | 9-0 | 8-1 |

| 2018 | 10-0 | ? |

Being well-versed in regression to the mean, we all know that a replication of last year’s magic is unlikely. Even so, we understand by investigation that anything seems possible to some extent, especially if we develop a Heisman Trophy winner this year a la 1951. As a sage high school teacher told the Scottsdale Progress in 1964 — our last undefeated season of the 20th century — “I think that’s why they play the game.”

No responses yet