Rally ’Round the Cannon: Out to Relaunch

I don’t know where I’m going from here, but I promise it won’t be boring. — David Bowie

Over the last couple years, here in the History Corner we have of needs revisited and investigated a number of lengthy trials in the University’s history; wars, epidemics, and the like. Various examples of slogging through protracted hard times give us context for current pandemic challenges and uncertainty, whether in examples of things to do — like sending books to thousands of Princetonians in the service for Christmas in 1943 — or alternatively things not to do — like simultaneously running three separate academic schedules during World War II, requiring various classes 365 days per year.

Then in July, we took a first look at normalizing life after huge disruption, in preparation for Princeton’s current vaccinated reopening. We recalled the fall of 1945, when euphoria over the end of World War II rapidly gave way to the pent-up planning for a new Princeton, hopefully prepared to improve, if only as a suitable legacy to the 355 alumni who died in the global conflagration. With professors, administrators, students, and even students’ wives reappearing around campus at seemingly random intervals from all over the world with new insight into how this might be accomplished, the potential seemed palpable, if not entirely focused. Today we resume that tale as the calendar turns to 1946 and the University, haphazardly awash in faculty, students, and staff with endless new sets of skills and ideas to be engaged, tries to get things organized and targeted to readdress its ongoing mission to serve the nation and, clearly in the immediate headlights, the world beyond.

The first post-war issue of The Daily Princetonian was published on Jan. 5, 1946, after a 35-month hiatus, to this day the only one in its 145-year history. On Feb. 6, 1943, it had bid farewell in a “Swan Song” for sheer lack of available staff with the acerbic subhead: “Littered Office Cleaned.” Now returned to the campus fray three days per week with a solemn promise to go daily — which took only two months to accomplish — the journal took a stab at getting its arms around the dozens of changes occurring on campus daily, with a masthead whose “Board of Publishers” included four students who had not appeared in any form on the prior one. By the end of the spring semester, the Prince was perking along, not only with endless academic schedule changes and re-debuts of dormant sports teams, but also reintroducing some gleeful muckraking. The undercard was the (probably distracted) failure of the trustees’ athletic board to approve an expense-paid trip by the newly-revived crew to a prestigious regatta in Seattle after the spring semester, which indeed made the board look petty. The main event was the refusal of the administration to approve the post-war reinstatement of the Princeton Tiger, with the naively accurate explanation that the 64-year-old humor magazine was not “in the best interest of the campus and University public relations.” This for a magazine which had at various times published Whitney Darrow ’31’s cartoons and Lewis Thomas ’33’s writing. On a campus where speakers such as socialist heavyweight Norman Thomas 1905 and American Communist Party chief Earl Browder were familiar, this handed the anti-censorship forces an unexpected rallying point, and they pounced, with the administration caving the following year. In the next decade, the Tiger would publish Henry Martin ’48’s cartoons and John McPhee ’53’s columns.

The world otherwise did seem to be coming back into its orbit, at least in part. After five years in the Air Corps, finishing as a colonel, Jimmy Stewart ’32 began shooting It’s a Wonderful Life for Frank Capra. On Broadway, Stewart’s Trianglebuddy Josh Logan ’31 went into production directing Irving Berlin’s new Annie Get Your Gun with Ethel Merman, with its anthem There’s No Business Like Show Business.

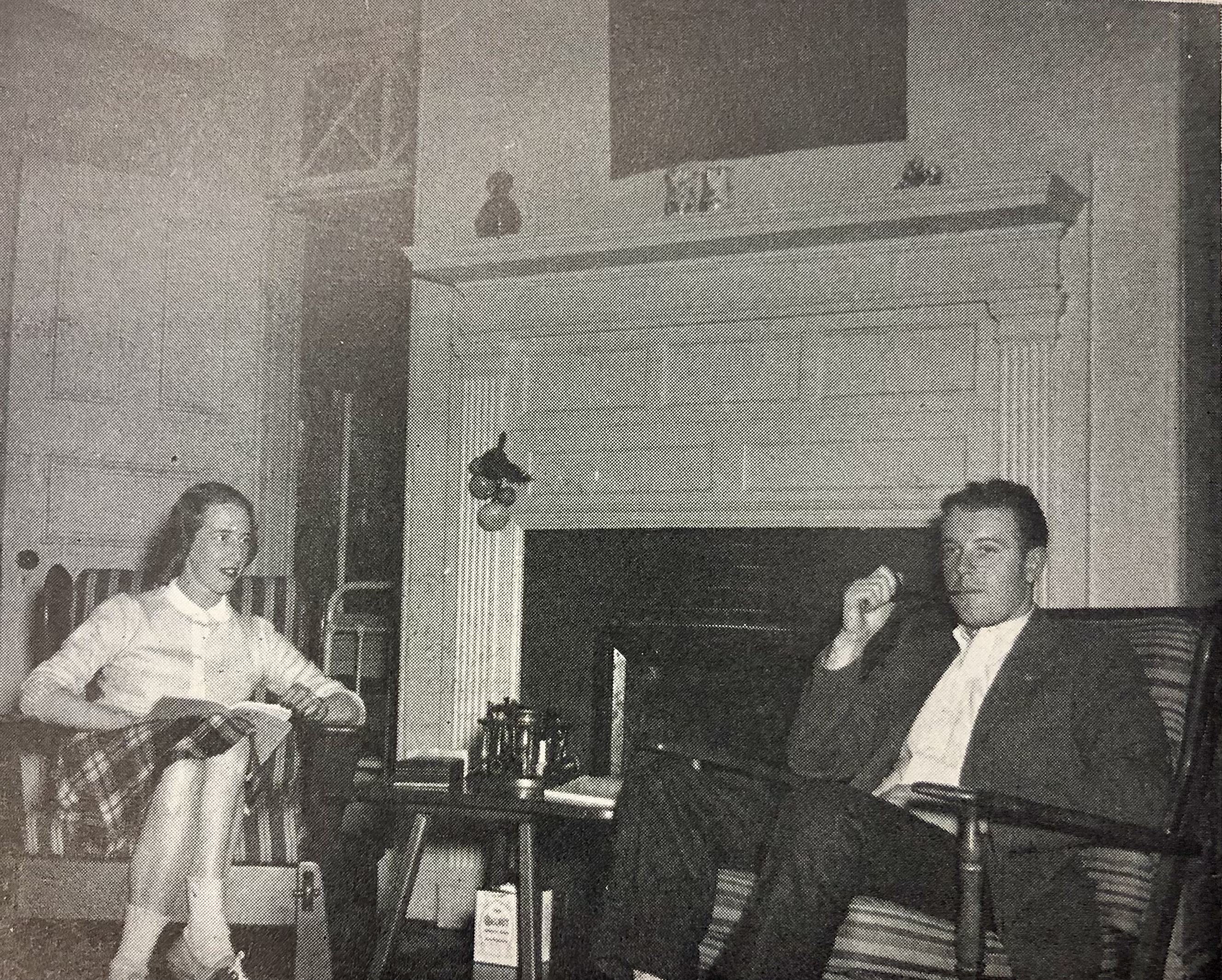

Unimagined vistas in Princeton life seemed suddenly inevitable. Consider this photo of Jack Sully ’45, newly returned and reenrolled, late of the 104th Infantry division and the Battle of the Bulge, and his lovely wife Patricia:

They are at home in their comfy new apartment, along with 37 other couples. In Brown Hall. Honest. They were subsequently married for 68 years, whether because of that or despite it. The University meanwhile received sympathetic permission from the town to erect the Butler housing tract for married students and junior faculty, using surplus Army barracks, to be used until replaced in less than five years. The last residents left in 2016.

Amid such new wrinkles popping up daily, the need to provide closure on the global nightmare just past was not neglected, if only because of the ubiquity of the experience, comprising tens of thousands of personal trials. The first attempt at healing for the entire Princeton community came at the annual Feb. 22 Alumni Day. The World War II Memorial book debuted in the atrium of Nassau Hall with 329 names of the dead inscribed (eventually to expand to 355), from classes ranging from 1909 to 1948, and nine graduate alumni. A special memorial service was held for the war dead in the afternoon (the annual University memorial service was then still at Reunions) and President Harold Dodds *1914 spoke on love of country and courage. Representatives of each of the 35 classes with deceased comrades marched in uniform as an honor guard for Alumni Association president Harold Helm 1920, who laid a wreath of Nassau Hall ivy in the chancel of the Chapel.

The last abbreviated term in Princeton history began March 1, 1946, and brought to a head the discussion over the elephant in the (lack of) room: the size of the school. Having laid plans to declare itself a university of world rank at its impending bicentennial, it faced the issue of whether its tacit pre-war limits of 2,400 undergraduate and 250 graduate students fit any reasonable model for its aspirations. That year 2,100 undergrads enrolled for the March 1 term, but the 450 mostly reenrolled grad students — wildly beyond estimates — were a suspected harbinger. The newly-repatriated Dean of the College Francis Godolphin 1924 took to PAW to warn that 2,600 undergrads were expected on campus in the fall — if there were no freshmen, clearly a non-starter. Plans for doubling up in dorms and expanding meals in clubs and Commons were underway, but where this would end was opened to discussion and possible options. Butler was part of the response, but so was an increased pressure on Annual Giving, which came through, raising $215,000 from over 8,000 alums, smashing prior records and surpassing Harvard in both categories. By September, 3,500 undergrads were enrolled, 75 percent of them veterans, crammed in everywhere. The debate over the composition of the student body heated up as well, with an unprecedented 50 foreign students already on campus and letters to the editor of PAW regarding the dearth of Black students, as well as other underrepresented brilliant public-high-school grads who had fought beside Princetonians from Dunkirk to Okinawa. The issue of women as students or faculty, although a smattering of both had been quietly present during the all-out war effort, apparently didn’t arise.

Only 169 men were in position to qualify for degrees at the June 20, 1946, Commencement ceremony in Alexander Hall. Looking at them and considering their absent brothers, President Dodds admonished those present — including nuclear researchers from the faculty — that “in this day of atomic bombs … the spirit and intelligence of man must exert itself with power to rise above mere bodily impulses. There is no other escape from domination by material greed and self-destroying selfishness.”

At the Victory Reunion that began two days later, the first in four years, an unheard-of 7,300 alumni (they were begged not to bring families) descended on the town for a gigantic blowout, far surpassing (and in many ways obscuring) its predecessor of 1919.

On July 1, the final four of Woodrow Wilson 1879’s 50 1905 Preceptor Guys — Christian Gauss, Robert K. Root, Edward S. Corwin, and Gordon Hall Gerould — retired, each having filled an endowed chair and leading role in American higher education for many years.

Seventy-five years ago, on Oct. 19, 1946, Princeton celebrated the bicentennial of its 1746 charter. President Dodds reassured the highly-esteemed audience in the jammed Chapel of the sturdiness of the University’s long roots in preparing it for the unimagined challenges to a free society in the future.

One of the 355 pages in the World War II Memorial book is that of Marine Lt. Ewing DeMange ’45, killed on Iwo Jima leading an infantry platoon in March 1945. According to his wishes, President Dodds later received a check from his estate for $1,191.49, accompanied by a letter from his father Ralph DeMange 1904. It was a repayment of the $1,000 scholarship awarded to Ewing by the Class of 1904 Memorial Scholarship Fund; the excess was the accrued interest since his matriculation, seemingly ages before, in the peacetime United States of September 1941.

No responses yet