Rally ’Round the Cannon: Victory, for Now

The importance of events, and of celebrating them

“When you’re falling in a forest and there’s nobody around

Do you ever really crash, or even make a sound?”

— Evan Hansen, Dear Evan Hansen, 2015

We earlier tackled the complexities of history’s almost-legendary We’re Number Two problem in the person of Aaron Burr Sr. (aka The Other One), Princeton’s second president. The issue arises again today, but on a grand scale.

Over 273 years, the University has had its share of occasions, large and small, that evolve into landmarks in spacetime, from the 1748 Commencement with the initial Latin salutatory to the arrival of James McCosh in 1868 to the renaming to Princeton University in 1896 coupled with Woodrow Wilson 1879’s “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” address, to the Great Train Robbery of 1963, to the senior class reciting Green Eggs and Ham to Dr. Seuss at Commencement in 1985, to the initial memorial service for the Princetonians who died on 9/11.

And you’ve almost certainly heard — if only here in the History Corner — of the great Victory Reunion of 1946, coincidentally in conjunction with the University’s Bicentennial. Alumni from every class held the major gatherings they had deferred in 1942-1945. Some 7,300 alums returned to celebrate the Allied triumph in World War II, and to honor those now absent. Every person with whom I’ve spoken who was there, most now themselves gone, described it as a transformative experience that altered their views of themselves and Princeton.

So it will likely surprise you to find this was not a unique or unprecedented occasion. From just about anything I’ve ever encountered in Princeton lore, the precedent of another Victory Reunion, following the anguishing trauma of World War I, has become an afterthought, if not a complete void, in the University’s history. Even now, from our vantage point 100 years later, it deserves much more than that, both in itself and for the unspoken lessons it tried to impart.

The war ended at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, with 40 million casualties, not counting the psychological trauma and xenophobia that ensued. On Dec. 21, an event forever tied to the war’s end for many Princetonians occurred at a French aerodrome: Hobey Baker 1914, with his orders home in his pocket, died testing an airplane and created a legend that persists today, when most other vestiges of the era are long forgotten.

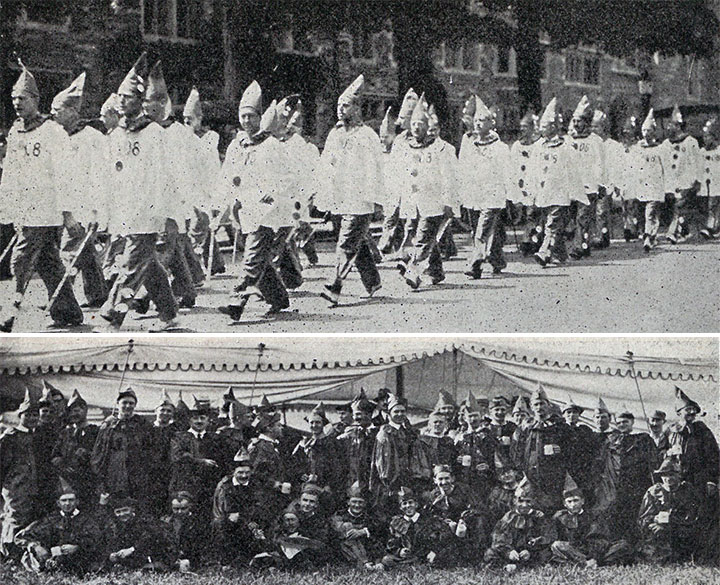

With alumni returning from wartime service, some began thinking about their upcoming reunions. By March of 1919, we can read class secretaries beating the drums in PAW, and by April, various logistical aspects of the celebration had started to take shape. The young alums would take over the open field where the computer science and Friend Center buildings now stand, at least 26 other classes would have “major” reunions at various spots around town — headquarters on campus did not appear until 1947 — and it was apparent every alumni residence and boarding house within 20 miles would come under frontal attack by those manically bent on returning and renewing. Not only the major classes that were suspended in 1917 and 1918, but a huge range of others, decided they couldn’t be left out, and the stage was set. The P-rade was scheduled for Saturday, June 14, providentially the fourth Flag Day (begun by President Wilson in 1916) — as if the boost were necessary; after Sunday Baccalaureate, a memorial service for all those killed in the war was to be held in the great Procter Hall at the Graduate College.

As a vibrant example, Secretary Edwin Simons of the Class of 1882 — pointedly the classmates of President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 — provided a teaser for the class’s delayed 35th reunion, to be held in town at the palatial home of classmate Malcolm MacLaren, a home that had previously belonged to legendary astronomer Charles “Twinkle” Young. The party was scheduled to start Friday night and continue through late Monday, following that year’s early Commencement. Come and party for five days, Simon wrote; you don’t want to be the only one who misses this and ends up shamed at the 40th. More than 5,500 Princetonians fought in the War, there may be 4,000 alums back, you’ll never see this again. Recall, the senior class in 1919 was 445 men. The total roll in the Class of 1882 at graduation had been 184.

This semi-spontaneous five-day block party, when extended over the 25 or 35 classes attending events of their own (1886, for example, hadn’t missed its 30th but decided to have a “Third-of-a-Century” reunion anyway), leaves intriguing questions. My favorite is a traditional event that seemed doomed to catastrophe. Clearly, many of the partygoers planned to hang around for Commencement on Monday. Great. They planned to be at the following alumni luncheon at University Gym. Fine. Then there would be the reception at Prospect. Wait, what? The president’s traditional farewell to the alums and their families was to be there per usual, but one suspects Mrs. Hibben — who remember, lived there, since this was long before the Faculty Club — may not have put the pieces together sufficiently to plan an overseas trip or otherwise avoid being crushed by a few thousand people. History seems blessedly mute on the outcome.

One thing we can say with confidence is that the planning for the event wasn’t complete as it began, since alums started rolling into town on Monday, June 9, a full week prior to Mrs. Hibben’s impending doom. By Friday, over 4,500 alums had turned up, and the number swelled to well over 5,000 by Saturday for the Flag Day display by the new Princeton Field Artillery unit (the predecessor of ROTC), the P-rade, and the Yale baseball game on University Field (Elis 5, Tigers 3). President Wilson missed his 40th reunion only because he was at the peace talks at Versailles; he sent an inspirational cable. That night front campus was illuminated as it had been for the 1896 Sesquicentennial, and Triangle held a then-unprecedented Reunions performance. “Our world is brighter for those three days,” offered the secretary of the 20th-reunion Class of 1899, “and we are better men.”

Many of the alums were still around for Commencement on Monday, and they afterward headed to the cavernous gym for the luncheon. The dais included trustees and honorary-degree recipients, but also two alumni generals and an admiral, and most pointedly Capt. L. Wardlaw Miles, a 46-year-old member of the English department. He had talked his way into a New York regiment in 1917 and, known as “the professor” to his men, led them into a brutal assault near the Aisne Canal in France on Sept. 14, 1918, eight weeks before the war ended. Suffering machine gun wounds in a shoulder and both legs, he forced his men forward from a stretcher and refused to leave the field until they took and held a German position, after which he was sent back to the aid station under protest. He was at the luncheon with his right arm in a sling and missing a leg, but displayed on his uniform were the Croix de Guerre and the Congressional Medal of Honor. After a tumultuous ovation, he joked that he had run into a former student of his on campus, who admitted he had never thought when in class that Miles “would pull anything like this.”

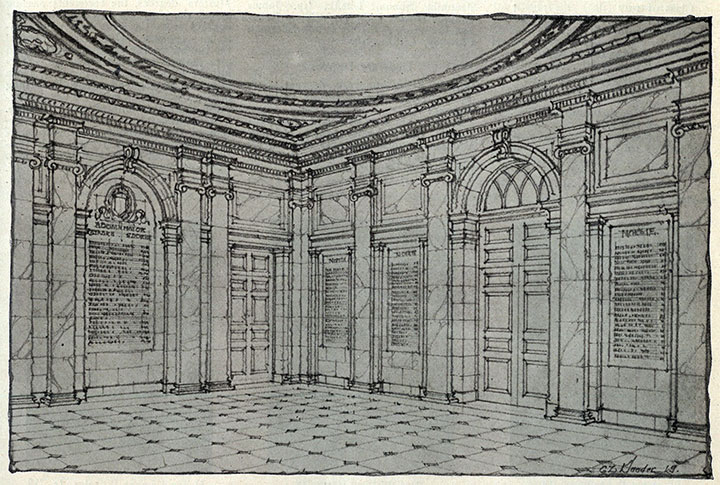

That week, drawings were unveiled for the marble War Memorial Hall in the Nassau Hall atrium, which had been designed by Day and Klauder. When finished later that year, it included the names of 152 Princetonians (21 alone from the self-professed “War Baby” Class of 1917) who had died in the World War, as well as those in earlier conflicts. It is inconceivable that anyone who experienced that and Miles’ address wouldn’t brave anything to see it never happened again.

But 355 more names were added following the next World War, and alumni gathered for the next Victory Reunion 27 years later. The one that’s remembered now.

No responses yet