Rally ’Round the Cannon: The Riot of 1963

Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.

— Lennon and McCartney, Strawberry Fields, 1967

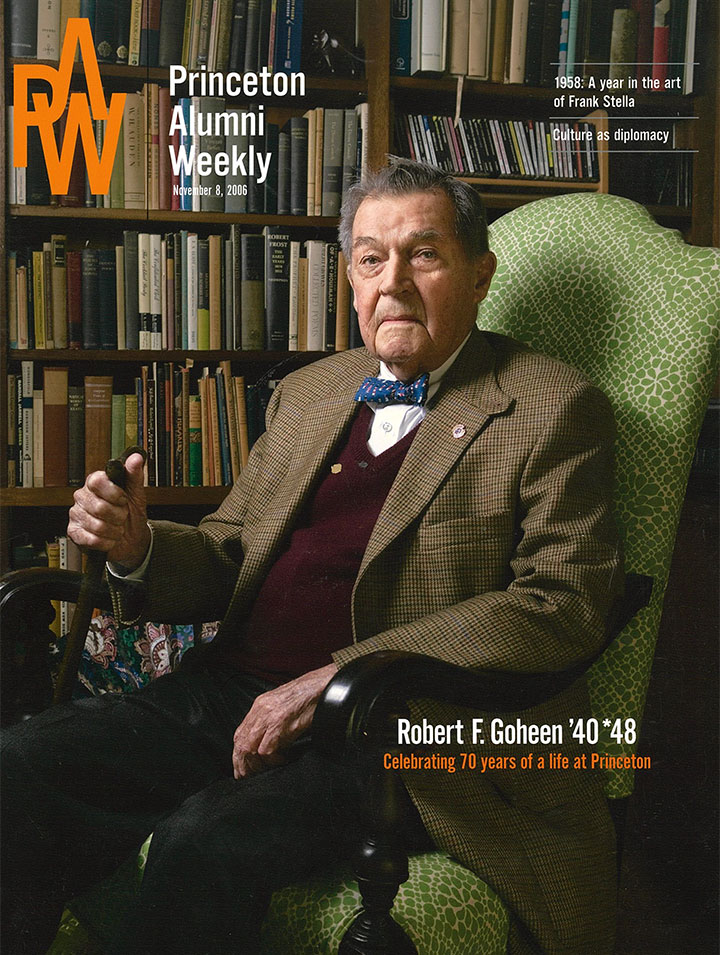

Once again, I am being confronted by the 1960s. My millennial friends regard this as good riddance, since we boomers managed to screw it up once already, but cold logic doesn’t necessarily help soften the impact. So you, the Ardent Historian, get to consider today not only the nuances of written communication through the decades, but also Ross Barnett, Joe Sugar ’54, the Proud Boys, running sap, the Choir College, Professor Sir W. Arthur Lewis, just about every aberrant psychology facet you can imagine, and of course baloney. Looking at that, I feel compelled to give away the ending, just so nobody at PAW Virtual HQ panics prematurely: Princeton president Bob Goheen ’40*48 saves the day. Twice.

In recent years, our gig here at History Central has suffered encroachment from all sorts of reportorial folks who have required new comparisons to describe the bizarritude surrounding current events. The Spanish Flu of 1918 is an obvious example. The newfound (and, hopefully, soon-to-be-reburied) prominence of Presidents James Buchanan and Warren G. Harding (and their flaming wreckage) is another. Virtually every detail of the Civil Rights Era of the ’60s has reemerged. Reaganomics simply will not die. You get the gist.

So when President Chris Eisgruber ’83 elected to choose historical allusion as a centerpiece of his annual president’s message to the mostly scattered University, it was certainly far from surprising. Correctly guessing that updates on athletic field relocation, dorm construction, and Nobel Prizes might not be top-of-mind for most of his constituents at the moment, he focused on the great and multilayered societal ferment of the last year and its importance to the future of the University. Words were not minced, regarding such as an American president “stok[ing] a mob that invaded America’s Capitol” and a U.S. Department of Education investigation that was “pure baloney.”

Rather than rehash the many and varied solicited campus exchanges of last year regarding combatting racism, following the killing of George Floyd and the national reanimation of Black Lives Matter, Eisgruber chose to highlight the pivotal stance by his predecessor Goheen in 1963 to the speaking invitation made by Whig-Clio to Gov. Ross Barnett of Mississippi, one of the country’s most vocal segregationists. While he publicly decried Barnett as unworthy of the invitation because of his persistent flouting of federal law, Goheen never suggested that the speech on Oct. 1 be stopped, nor of course that peaceful protest of it be limited, in line with the University’s historic dedication to free speech in pursuit of, as Eisgruber says, “truth-seeking.” He wants that spirit to inform Princeton’s current efforts to both understand and counteract racism in any way it can, locally or more widely. But it is humbling to note that object lesson is 58 years old.

Astonishingly, Eisgruber was not the first this year to raise Bob Goheen’s own complicated 1963 to me regarding our current difficulties. My new friend Dr. Ted Walworth of the Great Class of 1966 has, it seems, been spending some quality alone time (now there’s a phrase that will never be the same after COVID) digging through and organizing past treasures and keepsakes. He came across a four-page, single-spaced letter mailed from Goheen on May 15, 1963, to every one of the 3,000 Princeton undergrads. For that era, the physical production and distribution effort alone is impressive, never mind the length, never mind the middle of reading period. Walworth thought there might be a story in it. As Eisgruber illustrated but a few days later, there most certainly was. The letter’s subject was the Riot of 1963, which had involved 1,500 students rampaging between the train station and the Choir College for two or three hours the Monday night after Houseparties, May 6. It caused $5,500 worth of damage in town, paid for by student activity fees, and much more on campus. Eleven students were found guilty and fined in municipal court, 47 were disciplined by the college, and 11 were suspended for a year. It was by far the worst riot on campus since the last Christian Student fiasco in 1930, beyond the prior post-WWII low point, the Joe Sugar riot of 1953. And the precipitant cause? Precisely nothing, except maybe a full moon. It was like those stupid panty raids you see in ’30s movies, gone berserko. To complete the idiocy, the students felt the punishments too severe and then actually burned Goheen in effigy.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. Four days earlier, large numbers of students, both Black and white, had been fire-hosed, arrested and jailed in Birmingham, Alabama, by local police czar Bull Connor. Their crime: trying to shop together. The national press, all the way up to Time magazine, contrasted the two groups of demonstrators and (you won’t be shocked) concluded the Ivy Revelers were a bunch of spoiled, oblivious, myopic brats. Goheen made a public statement lambasting the “shocking display of individual and collective hooliganism on the part of young men who have no possible justification for sinking into it.” In his archives interview 51 years later he reiterates the stupidity, setting the fiasco forward as one motivator for his initiative to increase the number of minority students, through strategy meetings with admission head Alden Dunham ’53, then the tenured hire of globally respected economist W. Arthur Lewis and in 1964 bringing aboard Carl Fields to support the Black students on campus, two of the crucial Princeton staffing decisions of the 20th century. By the time Barnett turned up later that fall, things were already on the move, thanks ironically to the egomaniacal undergrads. When Barnett’s successor in bigotry, George Wallace, showed up to speak on campus in 1967, the five or six Black undergrads from four years prior had become 41, and their silent protest of his vitriol in Dillon Gym became a national press sensation.

That is part of what Goheen’s four-page letter to the students addresses, although in an expansive way that brings in an added concern. It begins by stating for the record Goheen’s understanding of the rites of spring argument (“the season when the sap runs”) before demolishing it as unworthy. Later, he explicitly brings up Birmingham and the unflattering national comparisons, only to note that adverse publicity is not why students are being punished, however apt the contrast may be. The reason lies in the very substance of what a riot actually is, and why that is antithetical to:

“…central objectives of the University: the advancement, in individuals, of rationally based powers of analysis and judgment; the encouragement of a sense of responsibility toward others, as well as for one’s own moral and spiritual self; the upholding of criteria for personal and communal conduct that dignify human life and do not degrade it.”

Goheen’s deconstruction of rioting itself is indeed why Ted Walworth forwarded the letter. I suspect it’s the reason a veteran of World War II would trouble to write a four-page missive to a bunch of basically clueless 20-year-olds. Here’s the excerpt Ted highlighted:

“There is a common, frightening characteristic of rioting that makes it far too dangerous to accept as a form of play, and that should severely limit any general approbation of rioting as a mechanism for social action. This is the ease and rapidity with which mass play or mass protest swings into a condition of mass hysteria, wherein individuals not only throw off common restraints but surrender much of their identity. Otherwise responsible persons cease to be persons, and in the ‘minds’ of those so involved, the rights and persons of others likewise become obliterated. The collective force of brute impulses rules the moment, and other persons lose significance except as they may chance to stand in the way and so become either interferences to or playthings for the mob. And such are the strange ways of the psyche that even after the event many involved don’t realize what happened to them or to what they have contributed.”

And there you have Jan. 6, 2021: six dead, hundreds of years pending in the Federal lockup, democracy in tatters. Anti-American in precisely the way the Riot of 1963 was anti-Princetonian, because each completely precluded the successful pursuit of the great missions of both: freedom of thought, freedom of inquiry, freedom of speech, and truth-seeking, all in the service of the nation and humanity.

Thank you, Ted. Thank you, Bob.

3 Responses

George Bustin ’70

4 Years AgoHigh Aptitude

I was not entirely sure where Dr. Lange was going with this essay, although I am perfectly familiar with his (apt) admiration for the late President Goheen. Has there ever been a clearer description of the dangers of mob action, and its impact on individual sense of responsibility, than the closing quotation from Dr. Goheen’s letter to the students of 1963? The final reference to the events of Jan. 6 is entirely apt — and explains very well what Dr. Lange had in mind all along. Nicely done.

Stephen Rickert ’65

4 Years AgoCharged for Riot Damage

During the “Riot of 1963,” I was a sophomore studying in Firestone Library. From outside the building, students jeered those of us inside as “weenie-wonks,” apparently for studying during a riot. Out of curiosity, I went outside to observe what was going on. The only damage I remember seeing was an automobile on fire on the north side of Nassau Street, I believe.

Later, I recall being informed that the University considered any student who was viewing the riot to be a “participant” for giving tacit approval of rioters’ misdeeds. To me, that implied that either I should have stayed in the library, tried to study and kept being jeered, or else I should have tried to stop the rioters!

My “share” of the damage ended up costing me $8.

Lawrence Phillips ’70

4 Years AgoResponse to Riot of 1963

Regarding “Rally ’Round the Cannon: The Riot of 1963” (published online March 4), Gregg Lange ’70’s always-lucid and compelling writing has once again provided a piece of Princeton’s history that relates to current events. President Robert Goheen ’40 *48’s thoughtful letter could be used to educate the participants in the Jan. 6 riots in Washington, D.C., if only they would choose to be instructed.

Curiosity leads me to ask what the response of the undergrads was to the letter at the time it was written. If any of them read Gregg’s piece, their response would be welcomed.